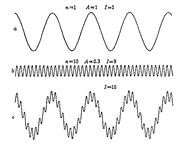

Invoking the analogy of sound, in fact, is not reading too much into their remarks, for they in fact do so by pointing out that the exact physical analogue of their overlays of cycles is that of sound waves being modulated together.

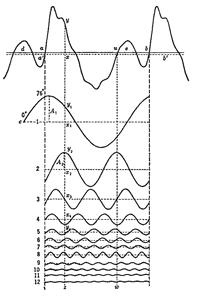

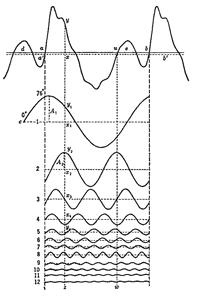

Again, as with their overlay of the 54- and nine-year cycles, note that the overall characteristic of the lower-frequency, longer-wavelength wave is preserved even with the grafting of the shorter higher frequency sound wave on to it. This process is called modulation, and in this instance, the longer lower frequency wave has become a carrier wave. They extend the wave modulation analogy even further, by pointing our that any wave of a particular wavelength and shape will have an overtone, or harmonic series, which are composed of fractions of that wavelength: one-half, one-third, one-fourth, one-fifth, and so on. They give the following chart of the graph of a sound wave from an organ pipe, and its first 12 overtones, or harmonics:

Harmonic Series of an Organ Pipe

Dewey and Dakin are strongly suggesting, then, that there may be a deeper physics of a wave mechanics involved in the overlay of economic cycles, and that correlations of sunspot activity with, for example, economic cycles of wholesale prices, may have a much deeper basis than merely the influence of the sun upon the weather, and of the weather on agricultural production and prices. In other words, they may both be immediate and manifest results of an underlying and more unified phenomenon.

But they go much further than even this, and in doing so, not only demonstrate that they are thinking in terms of a very deep, and indeed hyper-dimensional, physics, but also reveal some profound implications and questions that will preoccupy us throughout the remainder of this book. It is best to cite them at length in order to understand the full implications and significance of the deep physics connection that they are suggesting, and of its profound implications:

To that end let us consider in terms of modern psychology and physics a few facts important for our approach to economic science.

P.D. Ouspensky once asked his readers to make an experiment. Imagine, he said, that you live in two dimensions, instead of three. An easy way to do this is to imagine you are a being like a piece of paper, infinitely thin, living upon a table. You can look neither up nor down, for up and down are in a third dimension. You cannot even think up and down, or conceive it. For you have no thickness, and hence cannot even imagine thickness.

Now in the center of this tabletop where you live, there is cut a slot. In this slot there revolves a wheel, so hung that half the wheel is always below the table, and half of it above. This wheel is solid and you can see only the edge of it. Let us imagine its edge is painted in four colored segments black, white, blue, and red. As the wheel revolves, you observe it end-on, you of course do not know that it is a wheel you see. For you are a two-dimensional being, and therefore see only a single line of color along the tabletop. Occasionally, as the wheel slowly revolves, you do see that line change suddenly in color. Red will suddenly change to black, and black to white, white to blue, and blue to red again.

Now, if you observe this phenomenon long enough, you will finally decide that when the red comes up, it will eventually cause black; and when the black appears, it will eventually cause blue. You will think you know the causes of the phenomena you observe.

If a two-dimensional scientist is observing the phenomena, he will eventually discover a law in this continuity of event. Using this law, he will be able to predict changes of color accurately. The scientist, by the use of mathematics, might also discover that a third dimension was necessary to account for the real phenomenon he saw in two dimensions only. But neither of you could imagine this third dimension as a sensory reality. Nor could you know the real nature of the causes operating there. The scientist would admit this frankly, saying his law merely described what happened, without explaining it. But you, untrained in such fine distinctions, would speak boldly of a cause being followed by an effect. And each effect would in turn become a new cause (in your way of thinking) resulting in a further effect which followed. If you persisted in this belief, you might eventually resent being told that you knew nothing about the real causality.

Clearly, Dewey and Dakin are suggesting that what we call cause and effect are really but artifacts of our three-dimensionally-conditioned consciousness grappling with phenomena that have their origins in a hyper-dimensional world of more than three dimensions.

One might therefore add to their analogy of a hyper-dimensional world evidencing itself in cycles that our scientist might, by dint of the same sort of mathematical techniques, deduce a very different object the wheel as the real cause and effect of that which we perceive as a cycle. And this brings them to a vital fact:

What we call our recognition of cause and effect is somehow associated with time, and with our perception in time. This is important to understand, for what we call time is apparently only a mode of perception. Ouspensky, approaching the problem from a psychological background, goes so far as to suggest that time is the way we experience space in its higher dimensions. That is, the unknown dimensions of space are revealed to us in time.

In other words, not only are Dewey and Dakin suggesting that the sought-after deeper physics underlying their harmonic overlays and modulations of cycles might lie in a hyper-dimensional physics, but they are also suggesting that cause/effect thinking such as in the case of the sunspot-wholesale prices overlay cycle is in fact erroneous. It is not solar activity as the ultimate case, with weather modification as the mediate cause, and wholesale agricultural price changes as the final effect, but rather, the solar cycle, the fluctuation of weather, the fluctuation of prices might all be the immediate, though admittedly interrelated,