Jean Plaidy

The Plantagenet Prelude

Chapter I

DUCHESS AND QUEEN

From a window of the Chateau de lOmbriere the Duke of Aquitaine looked down on the scene in the shaded rose garden. It was one to enchant him. His two daughters - charming creatures both of them though the elder of the two, Eleonore, surpassed in beauty her sister Petronelle - were surrounded by members of the court, young men and women, decorative and elegant, listening now to the minstrel who was singing his song of love.

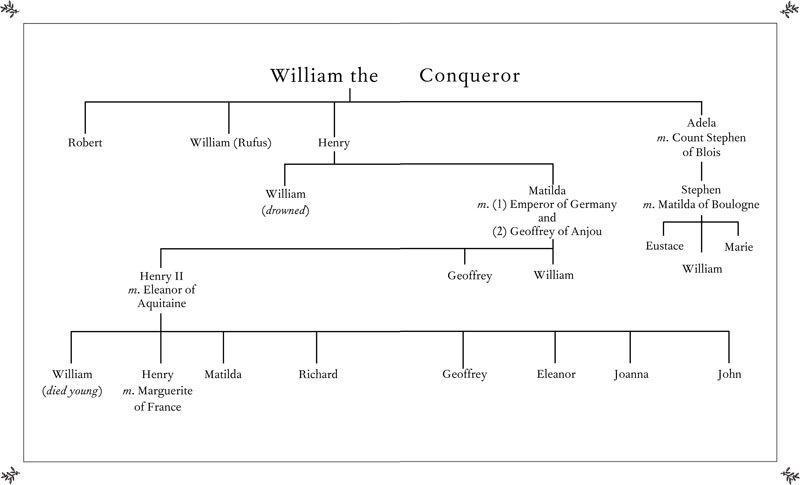

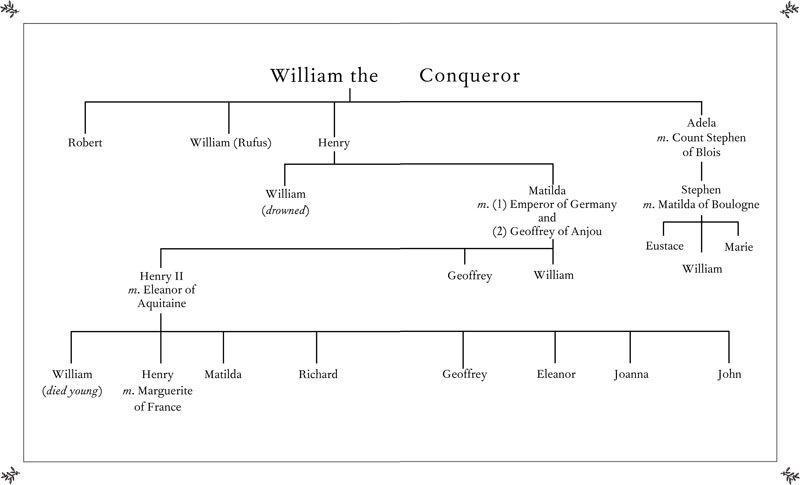

The Dukes eyes rested on Eleonore, for she was at the centre of the group. Some quality in her set her apart from the rest of the company. It was not only her beauty nor was it her rank. She was after all the heiress of Aquitaine until its Duke begot a son and, widowed as he was, he must bestir himself if he were to do so, for although he was but thirty-eight years of age, he had lost two wives and the only outcome of those marriages was his two girls Eleonore and Petronelle. Eleonore was tall and she was handsome; there was something commanding about her; she had the air of one born to rule. There was also a sensuality. He sighed, thinking of his father whose life had been dominated by his devotion to the opposite sex and wondering whether his attractive daughter would follow her grandfather in that respect.

She was fourteen years of age, Petronelle three years younger. Yet there was a ripeness about them both, even little Petronelle. As for Eleonore, she was ready for marriage. And if anything should happen to him before this event took place, who would protect her? He imagined her in her rose garden surrounded by her minstrels and the ladies of her court; and some suitor riding into the castle. There would not only be Eleonores vast lands and fortune to attract him but the fascinating Eleonore herself. And if she refused to marry? He knew the manners of the day. The lovely maiden would be abducted, held prisoner, deflowered if she would not yield willingly and placed in such a position that her family would be eager to marry her to her ravisher.

It was hard to imagine such a fate for Eleonore. Yet even she would be forced to submit.

He thanked God that it had not come to that. Here he was a man of thirty-eight with two attractive daughters. He must marry and beget a son. Yet what if he were to marry and there was no son? It was a logical assumption as so far there had been only daughters. How often were royal male heirs elusive. Why should he have been given only daughters? As was customary with men of his times he asked himself whether God was punishing him for his sins or perhaps the sins of his forbears.

His father had been one of the most renowned sinners of his age. Women had been his downfall. He had left his wife and set up his mistress in great state, even having an image of her engraved on his shield. William the ninth Duke of Aquitaine had cared nothing for convention, and although the greatest motive in his life had been the pursuit of women, this was a common enough quality - or failing depending on the way one looked upon it - and he was renowned rather for his love of poetry and song. This Dukes ideal state had been to lie with his mistress of the moment and listen to the strumming of the harp, and the songs, which were often of his own composing, sung by his minstrels. He was called the Father of the Troubadours and Eleonore had inherited his talent in this; she could compose a poem, set it to music, play it, sing it and attracted to her the finest songsters in the Duchy. What else had she inherited from her grandfather? Having noted the expression in those big languorous eyes as they rested on various comely gentlemen, the Duke wondered.

What he should do was get a son quickly and find a husband for Eleonore. But neither of these projects could be achieved without a great deal of thought. A husband for Eleonore now when she was the heiress could easily be found but it would be remembered that she could be displaced if her father had a son. And to have a son he must first find a wife! Not that that presented any great difficulty. What he must have was a fruitful wife. And there was the gist of the matter. Who could say until a man was married whether his wife would give him a son? What if he married to find the lady barren or capable only of giving him daughters?

So this was his dilemma. Should he marry again and try for a son? Or should he accept Eleonore as the heiress of Aquitaine? What of her husband if she married? Quite clearly, if she were to remain heiress of Aquitaine there was only one husband who would be worthy of her and that was the son of the King of France. So he was torn by doubts as he looked down on the scene, in the garden.

He sent for Eleonore. Because she was clever and could read and write - a rare accomplishment - because she already seemed to regard herself as the potential ruler of Aquitaine, because her mind was agile and to be admired as much as her beauty, he had talked to her for some time as he would have talked with some of his ministers.

She came in from the warm sun into the comparative chill of the castle, wrinkling her nose a little for the smell of rushes after the rose garden was none too pleasant. She would order the serving-man to sweeten the place. It should have been done a week ago. Rushes quickly became unpleasantly odorous.

Her father would be in his apartment which was reached by a staircase at the end of the great hall. This hall itself was the main room of the castle. It stretched from one end to the other and it reached up to the rafters. The ducal apartments were small in comparison for it was in the hall with its thick stone walls and narrow slits of windows that the court spent most of its time. Here courtiers danced and played the harp and sang; here the ladies sat and embroidered as they told tales and sang their songs; and because the castle could not accommodate them all they lived in houses close by where they could be within reach of the court.

Eleonore mounted the stairs to her fathers apartment.

He stood up as she entered and, placing his hands on her shoulders, drew her to him and kissed her forehead.

My daughter, he said, I would speak with you.

I guessed it, Father, since you asked me to come to you.

Some might have said commanded. Eleonore must be asked, never commanded, and graciously she granted the request.

Her father smiled at her. He would not have had her otherwise.

You know, Eleonore, my dear daughter, that I am deeply concerned.

For what reason?

I have no male heir.

She lifted her head proudly. And why should you need a male heir when you have a daughter?

Aye, a fine daughter. Mistake me not. I am aware of your qualities. But men seem to follow men.

They will be made to see that there are times when for their good they must follow a woman.

He smiled at her. I doubt not that you would make them understand that.

Then, Father, you have no problem. Come to the gardens and you shall hear my minstrels sing my latest song.

A treat I shall enjoy, my dear daughter. But it is suggested to me by my ministers that my duty lies in marriage.

Eleonores eyes blazed in sudden anger. Another marriage! A half-brother to displace her! That was something she would do everything in her power to prevent. She loved this fair land of Aquitaine. The people adored her. When she rode out they came out of their cottages to see her, to give many a heartfelt cheer. She believed that they would never feel so warmly towards any but herself. Oh, she was a woman and it may be that her sex was against her; but her grandfather, Duke William IX, had loved women, idealised women; he had instituted the Courts of Love; he had composed poetry and songs in favour of love, and women had been the most important factor in his life. So why should not the next ruler of Aquitaine be a duchess instead of a duke? It was what the people wanted. She herself wanted it; and Eleonore had already made up her mind that what she wanted she would have.