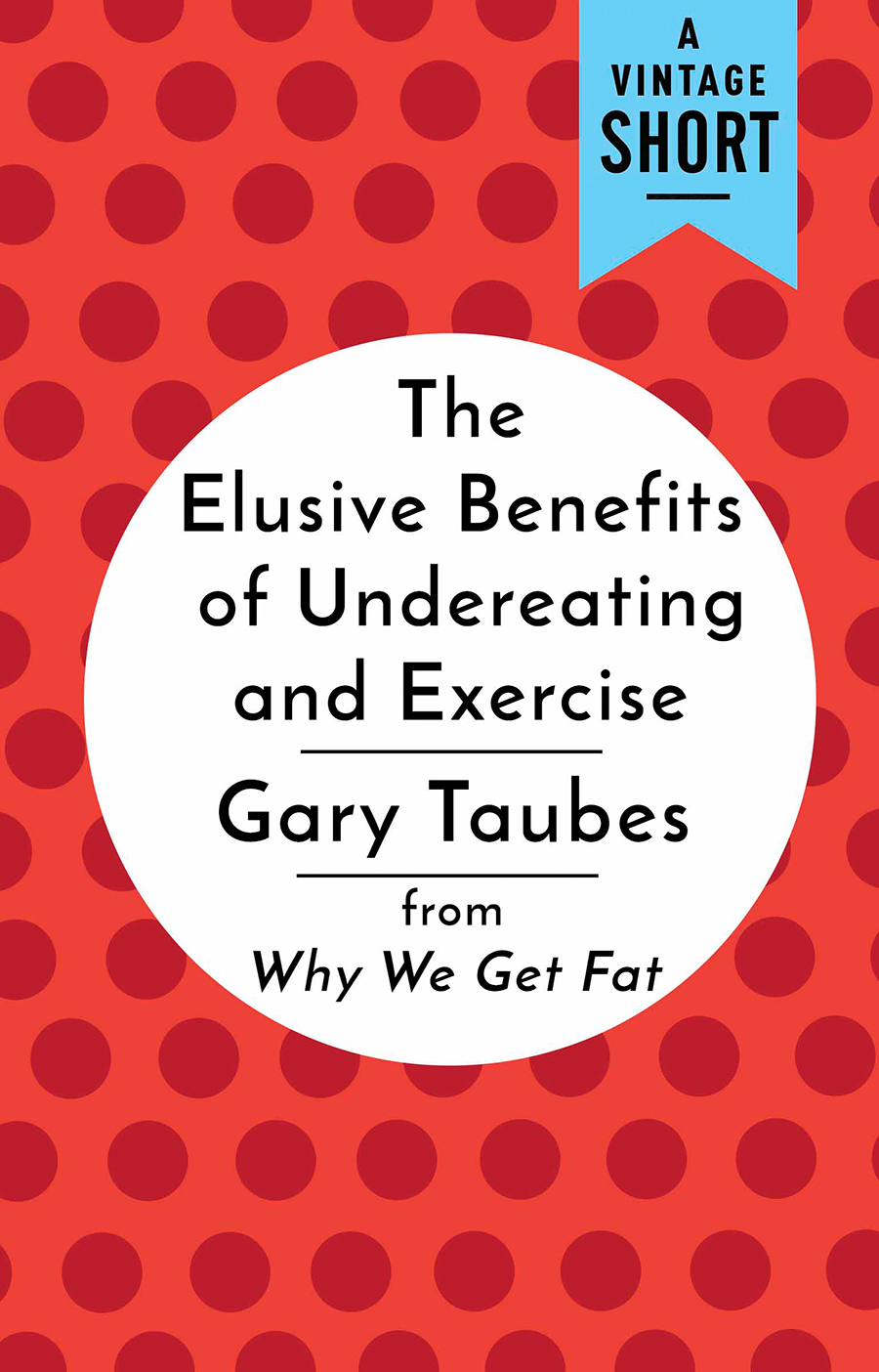

Gary Taubes

Gary Taubes is the author of Why We Get Fat and Good Calories, Bad Calories. He is a former staff writer for Discover and a correspondent for the journal Science. His writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic and Esquire, and has been included in numerous Best of anthologies, including The Best of the Best American Science Writing (2010). He has received three Science in Society Journalism Awards from the National Association of Science Writers. He is the recipient of a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Investigator Award in Health Policy Research and a cofounder of the Nutrition Science Initiative (NuSI). He lives in Oakland, California.

B OOKS BY G ARY T AUBES

The Case Against Sugar

Why We Get Fat: And What to Do About It

Good Calories, Bad Calories: Challenging the Conventional Wisdom on Diet, Weight Control, and Disease

Bad Science: The Short Life and Weird Times of Cold Fusion

Nobel Dreams: Power, Deceit, and the Ultimate Experiment

The Elusive Benefits of Undereating and Exercise

from Why We Get Fat

Gary Taubes

A Vintage Short

Vintage Books

A Division of Penguin Random House LLC

New York

Copyright 2010, 2011 by Gary Taubes

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover as a part of Why We Get Fat in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, in 2011.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data for Why We Get Fat is available from the Library of Congress.

Vintage eShort ISBN9780525435013

Cover design by Perry De La Vega

www.vintagebooks.com

v4.1

a

Contents

In the early 1990s, the National Institutes of Health set out to investigate a few critical issues of womens health. The result was the Womens Health Initiative (WHI), a collection of studies that would cost in the neighborhood of a billion dollars. Among the questions that the researchers hoped to answer was whether low-fat diets actually prevent heart disease or cancer, at least in women. So they enrolled nearly fifty thousand women in a trial, chose twenty thousand at random, and instructed them to eat a low-fat diet, rich in fruits, vegetables, and fiber. These women were given regular counseling to motivate them to stay on the diet.

One of the effects of this counseling, or maybe of the diet itself, is that the women also decided, consciously or unconsciously, to eat less. According to the WHI researchers, the women, on average, consumed 360 calories a day less on their diets than they did when they first agreed to participate. If we believe that obesity is caused by overeating, we might say that these women were undereating by 360 calories a day. They were eating almost 20 percent fewer calories than what public-health agencies tell us such women should be eating.

The result? After eight years of such undereating, these women lost an average of two pounds each. And their average waist circumferencea measure of abdominal fatincreased. This suggests that whatever weight these women lost, if they did, was not fat but lean tissuemuscle.

How is such a thing possible? If our weight is really determined by the difference between the calories we consume and the calories we expend, these women should have slimmed down significantly. A pound of fat contains roughly thirty-five hundred calories worth of energy. If these women were really undereating by 360 calories every day, they should have lost more than two pounds of fat (seven thousand calories worth) in the first three weeks, and more than thirty-six pounds in the first year. And these women had plenty of fat to lose. Almost half began the study obese; the great majority were at the very least overweight.

One possibility, of course, is that the researchers failed miserably at assessing how much these women ate. Maybe the women deceived the investigators and themselves as well. Maybe they didnt undereat by 360 calories a day. We have no idea what these women were really eating because, like most people when asked about their diet, they lied about it, as Michael Pollan suggested in The New York Times.

Another possibility is that this reduction in calories, this multiyear exercise in undereating, just didnt do what it was expected to do.

Of all the reasons to question the idea that overeating causes obesity, the most obvious has always been the fact that undereating doesnt cure it.

Yes, its true: If you are stranded on a desert island and starved for months on end, you will waste away, whether youre fat or thin to begin with. Even if you are just semi-starved, your fat will melt away, as will a good share of your muscle. Try the same prescription in the real world, though, and try to keep it up indefinitelytry to maintain the weight lossand it works very rarely indeed, if at all.

This should come as no surprise. As I suggested earlier, with the assistance of Hilde Bruchs wisdom and experience, most of us who are fat spend much of our lives trying to eat less. If it doesnt work when the motivation is merely decades of the intense negative reinforcement that accompanies obesitysocial ostracism, physical impairment, increased rate of diseasecan we really expect it to work just because an authority figure in a white coat insists that we give it a try? The fat person who has never tried to undereat is a rare bird. If youre still fat, as Bruch noted, thats a good reason to assume that undereating failed to cure you of this particular affliction, even if it has some short-term success at treating the most conspicuous symptomexcess adiposity.

The very first time anyone published a review of the efficacy of undereating as a treatment for obesitythe psychologist Albert Stunkard and his colleague Mavis McLaren-Hume, in 1959this was their conclusion. Nothing much has changed since. Stunkard said their study was motivated by what he called the paradox between his own failure to treat obese patients successfully at his New York Hospital clinic by restricting how much they eat and the widespread assumption that such treatment was easy and effective.

Stunkard and McLaren-Hume combed the medical literature and managed to find eight articles in which physicians reported on their success rates treating obese and overweight patients in their clinics. The results, said Stunkard, were remarkably similar and remarkably poor. Most of these clinics were prescribing diets that allowed only eight hundred or one thousand calories a daymaybe half what the WHI women said they were eatingand still only one in four patients ever lost as much as twenty pounds; only one in twenty patients managed to lose as much as forty pounds. Stunkard also reported on his own experience prescribing balanced diets of eight hundred to fifteen hundred calories a day to a hundred obese patients in his own clinic: only twelve lost as much as twenty pounds, and only one lost forty pounds. Two years after the end of treatment, Stunkard wrote, only two patients had maintained their weight loss.

The more recent assessments benefit from the use of computers and elaborate statistical analyses, but the results, as Stunkard might say, are still remarkably similar and remarkably poor. Prescribing low-calorie diets for obese and overweight patients, according to a 2007 review from Tufts University, leads, at best, to modest weight losses that are transientthat is, temporary. Typically, nine or ten pounds are lost in the first six months. After a year, much of what was lost has been regained.