Jean-Jacques Rousseau - The confessions of jean-jacques rousseau: complete

Here you can read online Jean-Jacques Rousseau - The confessions of jean-jacques rousseau: complete full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: Duke Classics, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The confessions of jean-jacques rousseau: complete

- Author:

- Publisher:Duke Classics

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The confessions of jean-jacques rousseau: complete: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The confessions of jean-jacques rousseau: complete" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

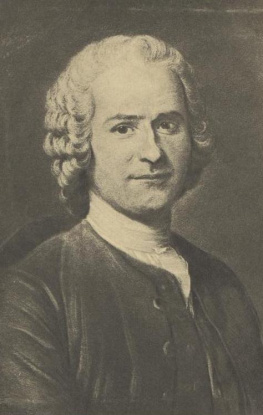

In addition to making his mark as a prominent philosopher, educational theorist, and musician, renaissance man Jean-Jacques Rousseau was also a pioneer in the genre of autobiographical writing. When his multi-book series Confessions was first published, it marked one of the most original entries in the literary category of autobiographies in centuries.

The confessions of jean-jacques rousseau: complete — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The confessions of jean-jacques rousseau: complete" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Complete

From a 1903 edition

ISBN 978-1-62012-913-5

Duke Classics

2012 Duke Classics and its licensors. All rights reserved.

While every effort has been used to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information contained in this edition, Duke Classics does not assume liability or responsibility for any errors or omissions in this book. Duke Classics does not accept responsibility for loss suffered as a result of reliance upon the accuracy or currency of information contained in this book.

Among the notable books of later times-we may say, without exaggeration,of all timemust be reckoned The Confessions of Jean Jacques Rousseau.It deals with leading personages and transactions of a momentous epoch,when absolutism and feudalism were rallying for their last struggleagainst the modern spirit, chiefly represented by Voltaire, theEncyclopedists, and Rousseau himselfa struggle to which, after manyfierce intestine quarrels and sanguinary wars throughout Europe andAmerica, has succeeded the prevalence of those more tolerant and rationalprinciples by which the statesmen of our own day are actuated.

On these matters, however, it is not our province to enlarge; nor is itnecessary to furnish any detailed account of our author's political,religious, and philosophic axioms and systems, his paradoxes and hiserrors in logic: these have been so long and so exhaustively disputedover by contending factions that little is left for even the mostassiduous gleaner in the field. The inquirer will find, in Mr. JohnMoney's excellent work, the opinions of Rousseau reviewed succinctly andimpartially. The 'Contrat Social', the 'Lattres Ecrites de la Montagne',and other treatises that once aroused fierce controversy, may thereforebe left in the repose to which they have long been consigned, so far asthe mass of mankind is concerned, though they must always form part ofthe library of the politician and the historian. One prefers to turn tothe man Rousseau as he paints himself in the remarkable work before us.

That the task which he undertook in offering to show himselfas Persiusputs it'Intus et in cute', to posterity, exceeded his powers, is atrite criticism; like all human enterprises, his purpose was onlyimperfectly fulfilled; but this circumstance in no way lessens theattractive qualities of his book, not only for the student of history orpsychology, but for the intelligent man of the world. Its startlingfrankness gives it a peculiar interest wanting in most otherautobiographies.

Many censors have elected to sit in judgment on the failings of thisstrangely constituted being, and some have pronounced upon him verysevere sentences. Let it be said once for all that his faults andmistakes were generally due to causes over which he had but littlecontrol, such as a defective education, a too acute sensitiveness, whichengendered suspicion of his fellows, irresolution, an overstrained senseof honour and independence, and an obstinate refusal to take advice fromthose who really wished to befriend him; nor should it be forgotten thathe was afflicted during the greater part of his life with an incurabledisease.

Lord Byron had a soul near akin to Rousseau's, whose writings naturallymade a deep impression on the poet's mind, and probably had an influenceon his conduct and modes of thought: In some stanzas of 'Childe Harold'this sympathy is expressed with truth and power; especially is theweakness of the Swiss philosopher's character summed up in the followingadmirable lines:

"Here the self-torturing sophist, wild Rousseau,

The apostle of affliction, he who threw

Enchantment over passion, and from woe

Wrung overwhelming eloquence, first drew

The breath which made him wretched; yet he knew

How to make madness beautiful, and cast

O'er erring deeds and thoughts a heavenly hue

Of words, like sunbeams, dazzling as they passed

The eyes, which o'er them shed tears feelingly and fast.

"His life was one long war with self-sought foes,

Or friends by him self-banished; for his mind

Had grown Suspicion's sanctuary, and chose,

For its own cruel sacrifice, the kind,

'Gainst whom he raged with fury strange and blind.

But he was frenzied,-wherefore, who may know?

Since cause might be which skill could never find;

But he was frenzied by disease or woe

To that worst pitch of all, which wears a reasoning show."

One would rather, however, dwell on the brighter hues of the picture thanon its shadows and blemishes; let us not, then, seek to "draw hisfrailties from their dread abode." His greatest fault was hisrenunciation of a father's duty to his offspring; but this crime heexpiated by a long and bitter repentance. We cannot, perhaps, veryreadily excuse the way in which he has occasionally treated the memory ofhis mistress and benefactress. That he loved Madame de Warenshis'Mamma'deeply and sincerely is undeniable, notwithstanding which he nowand then dwells on her improvidence and her feminine indiscretions withan unnecessary and unbecoming lack of delicacy that has an unpleasanteffect on the reader, almost seeming to justify the remark of one of hismost lenient criticsthat, after all, Rousseau had the soul of a lackey.He possessed, however, many amiable and charming qualities, both as a manand a writer, which were evident to those amidst whom he lived, and willbe equally so to the unprejudiced reader of the Confessions. He had aprofound sense of justice and a real desire for the improvement andadvancement of the race. Owing to these excellences he was beloved tothe last even by persons whom he tried to repel, looking upon them asmembers of a band of conspirators, bent upon destroying his domesticpeace and depriving him of the means of subsistence.

Those of his writings that are most nearly allied in tone and spirit tothe 'Confessions' are the 'Reveries d'un Promeneur Solitaire' and'La Nouvelle Heloise'. His correspondence throws much light on his lifeand character, as do also parts of 'Emile'. It is not easy in our day torealize the effect wrought upon the public mind by the advent of'La Nouvelle Heloise'. Julie and Saint-Preux became names to conjurewith; their ill-starred amours were everywhere sighed and wept over bythe tender-hearted fair; indeed, in composing this work, Rousseau may besaid to have done for Switzerland what the author of the Waverly Novelsdid for Scotland, turning its mountains, lakes and islands, formerlyregarded with aversion, into a fairyland peopled with creatures whosejoys and sorrows appealed irresistibly to every breast. Shortly afterits publication began to flow that stream of tourists and travellerswhich tends to make Switzerland not only more celebrated but more opulentevery year. It, is one of the few romances written in the epistolaryform that do not oppress the reader with a sense of languor andunreality; for its creator poured into its pages a tide of passionunknown to his frigid and stilted predecessors, and dared to depictNature as she really is, not as she was misrepresented by the modishauthors and artists of the age. Some persons seem shy of owning anacquaintance with this work; indeed, it has been made the butt ofridicule by the disciples of a decadent school. Its faults and itsbeauties are on the surface; Rousseau's own estimate is freely expressedat the beginning of the eleventh book of the Confessions and elsewhere.It might be wished that the preface had been differently conceived andworded; for the assertion made therein that the book may prove dangeroushas caused it to be inscribed on a sort of Index, and good folk who neverread a line of it blush at its name. Its "sensibility," too, is a littleoverdone, and has supplied the wits with opportunities for satire; forexample, Canning, in his 'New Morality':

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The confessions of jean-jacques rousseau: complete»

Look at similar books to The confessions of jean-jacques rousseau: complete. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The confessions of jean-jacques rousseau: complete and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.