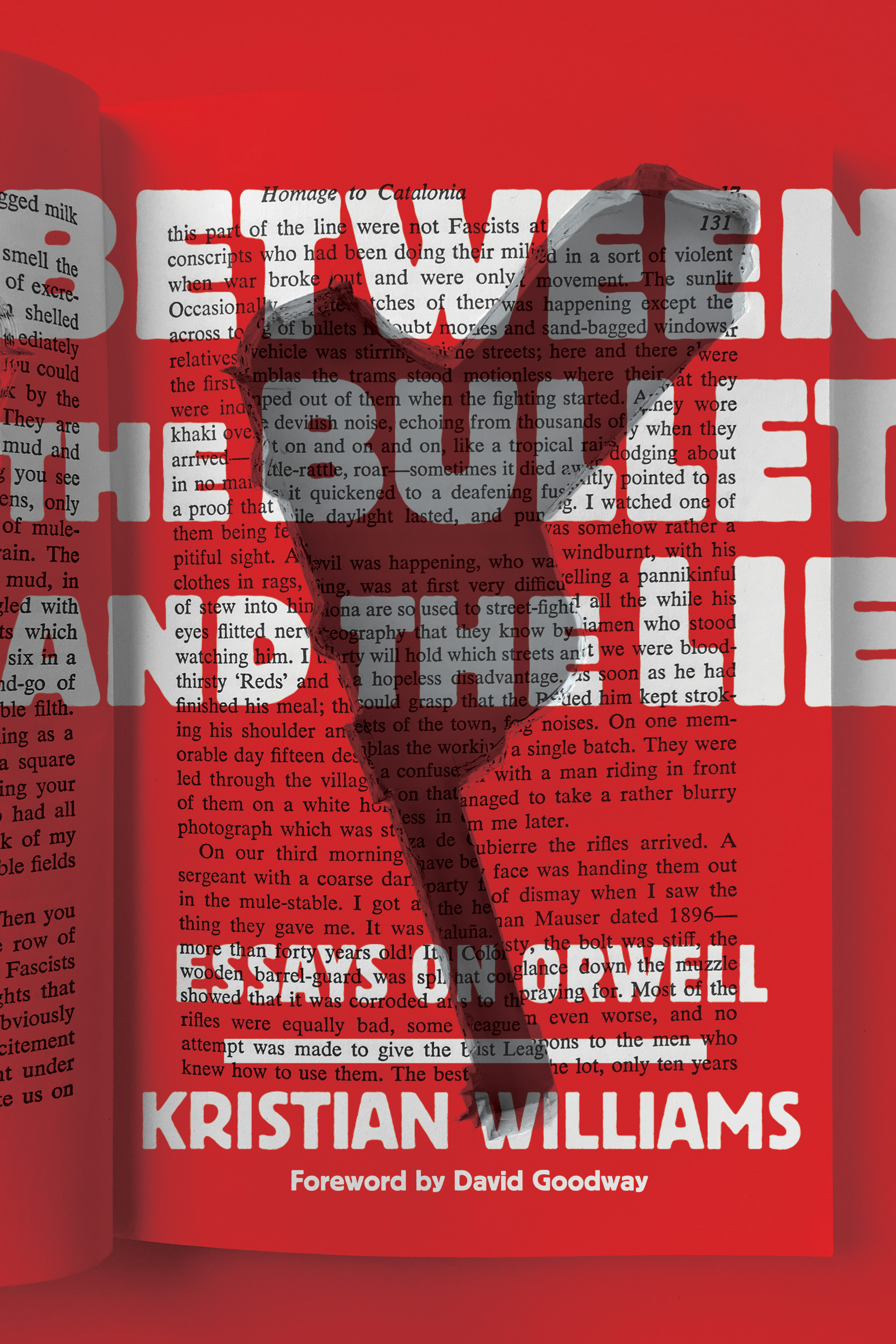

Foreword: Williamss Orwell

Oh, no, not another book about Orwell ! Here is a writer whose expressed wish was that there was to be no biography, yet there are now half a dozen. An Orwell Society was founded in 2011 and has since launched a biannual academic journal, George Orwell Studies . The revelation in 2013 by Edward Snowden, National Security Agency contractor and whistleblower, of the scale of the global surveillance systems operated by the intelligence agencies of the USA and United Kingdom has led to their description as Orwellianin reference to the controlling intrusion by the state detailed so nightmarishly in 1984 . Online sales of the novel mushroomed by 5,800 percent within a week of Snowdens action. The inanities, unfortunately usually malign, of the Trump presidency, also have one reaching for Orwell: what could be more Orwellian than the concept of alternative facts? Kellyanne Conways coinage caused 1984 to jump to the top of Amazons bestseller list, an unprecedented achievement for a book first published sixty-eight years previously. As a friend informs me, Orwells now hot in the States, you know.

Concurrently, my reading has led me to appreciate how difficult the man could be in person. V.S. Pritchett, short-story writer and critic, who memorably called him the wintry conscience of a generation, not only described him as complex, straying, and contradictory but seems to have regarded him as an eccentric crank, and thorn in the flesh, commenting that to become his friend you first had to undergo the usual quarrel. Herbert Read rightly considered that he had raised journalism to the status of literature and felt nearer to him than to any other English writer of our time, yet was all the same irritated by some aspects of his personality, including his proletarian pose in dress. Read might also have mentioned the ostentatious drinking of tea from his saucer, slurping it noisily, one of the habits that greatly irked John Morris, a wartime colleague at the BBC Easter n Service.

Morris, a conventional man who disliked Orwell, surprises by observing:

Although he wrote so well, he was a poor and halting speaker; even in private conversation he expressed himself badly and would often fumble for the right word. His weekly broadcast talks were beautifully written, but he delivered them in a dull and monotonous voice. I was often with him in the studio and it was painful to hear such good material wasted: like many other brilliant writers, he never really understood the subtle differences between the written and the spoken word, or, if he did, he could not be bothered with them.

Although Orwell remains controversial in many ways, there is extensive recognition that his work was indeed beautifully written, even that he is one of the masters of Engl ish prose.

Any writer, I am convinced, writes as well as they read. Kristian Williams knows his Orwell inside outthere is nothing pertinent with which he does not appear familiarand so the prose of this exceptional book, which I am privileged to introduce, is exquisitely straightforward. Attention to the quality of writing is not to be dismissed as a mere artistic or aesthetic fad, irrelevant to the major issues of the day, to the fundamental concerns of life. On the contrary, Kristian and myself, and Orwell, too, passionately believe in the writers responsibility to make accessible to the ordinary intelligent reader ideas and analysis however strange or difficult.

It is the duty of the communicator to communicate, not to revel in obscurantist, even if supposedly technical, language that only experts pretend to understand. As Kristian remarks in his int roduction:

Orwell is not renowned as a deep thinker, partly because deep thinking has become confused with difficult writingthat is to say, with writing that is difficult to read. It is in fact harder to produce smooth, clear prose, but readers are prone to assume that if they do not struggle over a passage then the writer must not have either. They are just as likely to supposeor a certain type of reader is, anywaythat if a piece of writing is obscure it is also necessarily profound.

It was probably G.K. Chesterton who apologized to an editor for submitting an overlong article, explaining that he had not had time to write a shorter piece. Kristian explains that Orwell wanted his prose to be like a window pane, so transparent one forgets that i ts there.

Between the Bullet and the Lie collects essays several of which have been previously published. The second part applies Orwells outlook to a range of contemporary issues, whereas the first, especially rich and impressive, discusses both decency (always his touchstone) and human imperfection and compares at some length the homophobic Orwell with Oscar Wilde. With typical unpredictability and contradiction, Orwell insisted that he had always been very p ro-Wilde.

Kristian describes himself as an anarchist with social-democratic sympathies, whereas Orwell wasand this is extremely well puta democratic socialist with anarchist sympathies. His appeal, however, is remarkably broad, and he can not unreasonably be claimed by a variety of incompatible ideologies: state socialism as well as libertarian socialism, of course, but in addition conservatism, nationalism, liberalism, even Trotskyism. Notably absent from this spectrum of admiration are most Marxists, apologists, whether past or present, for the Soviet Union, and advocates of utopian communism. They continue to hate him for spilling the Spanish beans in Homage to Catalonia , for his fable of revolutionary degeneration Animal Farm and above all, I believe, for the dystopia of 1984 . The Bolsheviks, he had argued in 1941, sought to create a Rule of the Saints, which, like the English Rule of the Saints, was a military despotism enlivened by witchcraf t trials.

I have already directed attention to Orwells contradictions and the impossibility of much of his behavior. Recognizing how imperfect, how flawed he himself was, philosophically he was an anti-perfectionist, and this entailed an anti-utopianism. In a central passage Kristian ably s ummarizes:

Orwell wrote against Utopia, not merely because he believed it impossible, and not simply because it might become perverted, but also because he found the very idea of perfection repulsive and even oppressive. In his essay on Jonathan Swift, Orwell worries over the totalitarian tendency which is implicit in the anarchist or pacifist vision of society.The problem, as Orwell saw it, is that Utopias, by definition, are perfect and that human beingsalso by definitionare not. Always the realist, he concludes that the fault lies with Utopia: that these dreams of a perfect society are not only impossible, but inhuman and therefore, by human standards, undesirable. Were they realized, the practical result could only be a narrowing of the scope of h uman life.

The problem then lies not just in a dystopia like 1984 , but also in seemingly benign utopias such as Wellss A Modern Utopia and Huxleys Island : the quest for perfection makes us all l ess human.

This disquisition appears in the chapter on Wilde; and Kristian concludes that his utopianism and Orwells anti-utopianism are equally necessary, that we do not need to choose between them. Wilde memorably maintained: A map of the world that does include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. Yet the continuationAnd when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sailKristian considers as tragic as Orwells position. Indeed throughout his book, his stance is almost always the same as that of Orwell, fruitfully applying the approach the older writer arrived at in the unhappy second quarter of the twentieth century to the probably even more desperate second decade of the twenty-first. Thus he applauds Orwells reverence for fact, his sense of decency, his respect for intelligence, his faith in the common people, his courage (moral, intellectual, and physical), and his refusal to mock traditional virtues for the sake of looking sophisticated, commenting that these are qualities disastrously lacking in our present discoursepolitical and cultural, Left and Right, popular and intellectual. Kristian stresses that it is essential for radical ideas to address the world as it actually is, as we find it in our lives rather than in our daydreams or our theories. He rejects the sense of ideological purity in which alleged radicals luxuriate: