Uncommon Knowledge

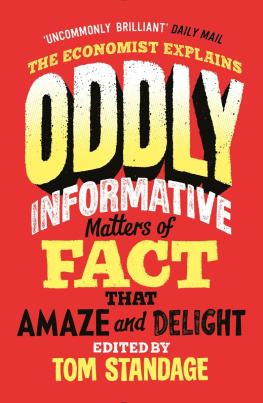

Tom Standage is deputy editor of The Economist and the author of six books, including A History of the World in 6 Glasses. His writing has also appeared in the New York Times, the Daily Telegraph, the Guardian and Wired. Uncommon Knowledge is the sequel to Go Figure and Seriously Curious, also edited by him.

Published in 2019 under exclusive licence from The Economist by

Profile Books Ltd

29 Cloth Fair

London EC1A 7JQ

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright The Economist Newspaper Ltd 2019

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The greatest care has been taken in compiling this book. However, no responsibility can be accepted by the publishers or compilers for the accuracy of the information presented.

Where opinion is expressed it is that of the author and does not necessarily coincide with the editorial views of The Economist Newspaper.

While every effort has been made to contact copyright-holders of material produced or cited in this book, in the case of those it has not been possible to contact successfully, the author and publishers will be glad to make amendments in further editions.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781788163323

eISBN 9781782835981

Contents

Introduction: The joy of uncommon knowledge

EVERYTHING THAT IS NEW or uncommon raises a pleasure in the imagination, wrote Joseph Addison, an English essayist and poet, because it fills the soul with an agreeable surprise, gratifies its curiosity, and gives it an idea of which it was not before possessed. He was writing in 1712, but today, more than three centuries later, his remark neatly summarises the objective of this book.

This is a compendium of explanations, and what they all have in common is that they are uncommon: a word that has two meanings. On the one hand, it refers to things that are rare or infrequently encountered. In the realm of knowledge, that means things that not many people are aware of or know about. But these unusual explanations also have the power to stretch your mind and subtly change how you see the world. In other words, they are uncommon in the second sense of the word, which means exceptional and extraordinary. As Addison observed, uncommon knowledge is enjoyable to encounter because it is unexpected and surprising; because a neat explanation is mentally satisfying; and because encountering a previously unfamiliar idea, and storing it away for future reference, expands the intellect.

Many people would be surprised to hear that the global suicide rate is falling; that most refugees do not live in camps; that carrots were not originally orange; or that the far side of the Moon isnt always dark. They probably couldnt explain why donkey skins are the new ivory; why Westerners are eating so much more chicken; why Americans are sleeping longer than they used to; or why death is getting harder to define. These arent the sorts of things you wonder about every day. But when you learn the underlying explanations, you do not merely learn something that most people dont know you also broaden your perspective just a little bit, as your mind makes room for a new way of looking at things. That is the joy of uncommon knowledge, in both senses of the word.

Rooting out these appetising intellectual morsels is something we love to do at The Economist, and this book brings together unexpected explanations and fascinating facts from our output of explainers and daily charts. We hope you will enjoy this collection of the fruits of our never-ending quest to uncover the mechanisms that explain why the world is the way it is. By the time you reach the last page, you will have learned things you did not know before and you will also have equipped your mind to understand the world more fully. Read this book, and you will join the ranks of the uncommonly knowledgeable.

Tom Standage

Deputy Editor, The Economist

April 2019

Uncommon knowledge: little-known explanations to stretch your mind

Why Swazilands king renamed his country

The King of Swaziland, Mswati III, has a problem. Whenever we go abroad, he says, people refer to us as Switzerland. So on April 18th 2018, at a celebration marking the 50th anniversary of the countrys independence from Britain, the king announced that he was changing Swazilands name to eSwatini. (As an absolute monarch he can make such decisions.) With its lower-case e, this new name might seem at first glance to be an attempt to rebrand one of the worlds last remaining absolute monarchies as something a little more modern for the internet age. But the new name in fact simply means Land of the Swazis.

Whether many people did in fact confuse Swaziland with Switzerland is unclear. Both are gorgeous mountainous countries with small populations. Both are landlocked and surrounded by bigger neighbours. But the differences are perhaps more striking. As well as being ruled by a man with 15 wives, Swaziland is a poor country with the highest rate of HIV infection in the world. Some 26% of the adult population is infected. That in turn contributes to a life expectancy at birth of 58 years, the 12th-worst in the world. Changing the name from Swaziland to eSwatini strikes some people as a distraction from bigger issues.

Nonetheless, the kings decision did have a logic to it. Many other former British colonies in Africa took new names on becoming independent. The Gold Coast became Ghana; Northern Rhodesia and Southern Rhodesia became Zambia and Zimbabwe respectively. Basutoland, a tiny enclave surrounded by South Africa, became Lesotho. Swazilands transformation into eSwatini was much the same story, serving to distance the country from its colonial past, albeit 50 years after the separation. The king had in fact long used the new name in addresses to the United Nations and at the opening of his countrys parliament.

But it is likely to take some time to get Swaziland accepted as eSwatini. The Czech Republic is still rarely referred to as Czechia in English, despite the best efforts of its government over the past few years to promote the name. In the case of eSwatini, maps and globes will obviously have to be updated, and so will their modern replacements: Google Maps is still using the old name. Within the country, many institutions will have to be renamed. The Royal Swaziland Police, the Swaziland Defence Force, and the University of Swaziland all come to mind. Indeed, the constitution may even have to be rewritten to make sure that the new name sticks.

Why terrorists claim credit for some attacks but not others

Two terrorist attacks hit the southern Philippines in the final days of January 2019. The first, a double bombing at a Roman Catholic church on January 27th, killed at least 20 people. A few days later, an attack on a mosque claimed the lives of two Muslim religious leaders. The jihadists of Islamic State quickly claimed responsibility for the first attack, but the perpetrators of the latter remain unknown.

These attacks were representative of a broader trend. In the past two decades, fewer than half of all terrorist attacks have been either claimed by their perpetrators or convincingly attributed by governments to specific terrorist groups. A paper by Erin Kearns of the University of Alabama, covering 102,914 attacks committed in 160 countries between 1998 and 2016, reveals a consistent pattern to these claims and attributions. Her study shows that attacks causing few deaths, like the assault on the Philippine mosque, tend to remain anonymous. But very deadly ones, such as the attack on a Nepalese military base that killed at least 170 soldiers in 2002, are also less likely than average to be claimed or attributed particularly when aimed at a military or diplomatic target. Instead, it is those in the middle, causing around 100 deaths, whose perpetrators are most often identified.