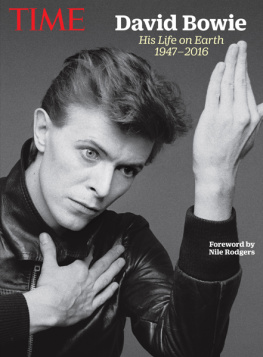

ON BOWIE

SIMON CRITCHLEY

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Serpents Tail

3 Holford Yard, Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Text copyright 2014, 2016 Simon Critchley

Illustrations 2014, 2016 Eric Hanson

An earlier version of this book was published as Critchley: Bowie by OR Books, New York, 2014

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in New Caledonia and Alternate Gothic to a design by Courtney Andujar/Bathcat Ltd.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library.

208pp

e-ISBN 978-1782833062

LET ME BEGIN WITH A RATHER EMBARRASSING confession: no person has given me greater pleasure throughout my life than David Bowie. Of course, maybe this says a lot about the quality of my life. Dont get me wrong. There have been nice moments, some even involving other people. But in terms of constant, sustained joy over the decades, nothing comes close to the pleasure Bowie has given me.

It all began, as it did for many other ordinary English boys and girls, with Bowies performance of Starman on BBCs iconic Top of the Pops on July 6 1972, which was viewed by more than a quarter of the British population. My jaw dropped as I watched this orange-haired creature in a catsuit limp-wristedly put his arm around Mick Ronsons shoulder. It wasnt so much the quality of the song that struck me; it was the shock of Bowies look. It was overwhelming. He seemed so sexual, so knowing, so sly and so strange. At once cocky and vulnerable. His face seemed full of sly understanding a door to a world of unknown pleasures.

Some days later, my mother Sheila bought a copy of Starman, just because she liked the song and Bowies hair (shed been a hairdresser in Liverpool before coming south and used to insist dogmatically that Bowie was wearing a wig from the late 1980s onward). I remember the slightly menacing black and white portrait photo of Bowie on the cover, shot from below, and the orange RCA Victor label on the seven-inch single.

For some reason, when I was alone with our tiny mono record player in what we called the dining room (though we didnt eat there why would we? there was no TV), I immediately flipped the single over to listen to the B side. I remember very clearly the physical reaction I felt listening to Suffragette City. The sheer bodily excitement of that noise was almost too much to bear. I guess it sounded like sex. Not that I knew what sex was. I was a virgin. Id never even kissed anyone and had never wanted to. As Mick Ronsons guitar collided with my internal organs, I felt something strong and strange in my body that Id never experienced before. Where was suffragette city? How did I get there?

I was twelve years old. My life had begun.

THERE IS A VIEW THAT SOME PEOPLE CALL narrative identity. This is the idea that ones life is a kind of story, with a beginning, a middle and an end. Usually there is some early, defining, traumatic experience and a crisis or crises in the middle (sex, drugs, any form of addiction will serve) from which one miraculously recovers. Such life stories usually culminate in redemption before ending with peace on earth and goodwill to all men. The unity of ones life consists in the coherence of the story one can tell about oneself. People do this all the time. Its the lie that stands behind the idea of the memoir. Such is the raison dtre of a big chunk of what remains of the publishing industry, which is fed by the ghastly gutter world of creative writing courses. Against this, and with Simone Weil, I believe in decreative writing that moves through spirals of ever-ascending negations before reaching nothing.

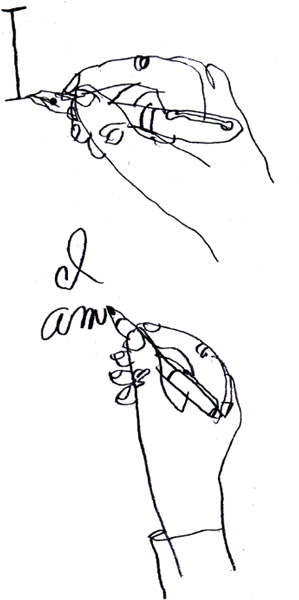

I also think that identity is a very fragile affair. It is at best a sequence of episodic blips rather than some grand narrative unity. As David Hume established long ago, our inner life is made up of disconnected bundles of perceptions that lie around like so much dirty laundry in the rooms of our memory. This is perhaps the reason why Brion Gysins cut-up technique, where text is seemingly randomly spliced with scissors and which Bowie famously borrowed from William Burroughs gets so much closer to reality than any version of naturalism.

The episodes that give my life some structure are surprisingly often provided by David Bowies words and music. He ties my life together like no one else I know. Sure, there are other memories and other stories that one might tell, and in my case this is complicated by the amnesia that followed a serious industrial accident when I was eighteen years old. I forgot a lot after my hand got stuck in a machine. But Bowie has been my soundtrack. My constant, clandestine companion. In good times and bad. Mine and his.

Whats striking is that I dont think I am alone in this view. There is a world of people for whom Bowie was the being who permitted a powerful emotional connection and freed them to become some other kind of self, something freer, more queer, more honest, more open, more exciting. Looking back, Bowie was a kind of touchstone for that past, its glories and its glorious failures, but also for some kind of constancy in the present and for the possibility of a future, even the demand for a better future. Bowie was not some rock star or a series of flat media clichs about bisexuality and bars in Berlin. He was someone who made life a little less ordinary for an awfully long time.

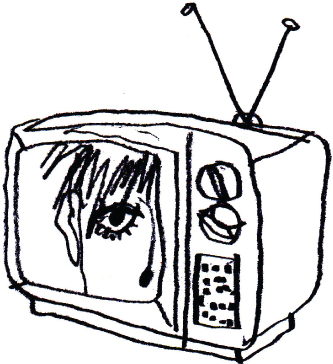

AFTER ANDY WARHOL HAD BEEN SHOT BY Valerie Solanas in 1968, he said, Before I was shot, I suspected that instead of living Im just watching TV. Since being shot, Im certain of it. Bowies acute ten-word commentary on Warhols statement, in the eponymous song from Hunky Dory in 1971, is deadly accurate: Andy Warhol, silver screen / Cant tell them apart at all. The ironic self-awareness of the artist and their audience can only be that of their inauthenticity, repeated at increasingly conscious levels. Bowie repeatedly mobilises this Warholian aesthetic.

The inability to distinguish Andy Warhol from the silver screen morphs into Bowies continual sense of himself being stuck inside his own movie. Such is the conceit of Life on Mars?, which begins with the girl with the mousy hair, who is hooked to the silver screen. But in the final verse, the movies screenwriter is revealed as Bowie himself or his persona, although we cant tell them apart at all:

Next page