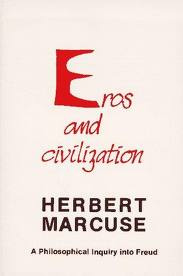

EROS AND CIVILIZATION

Herbert Marcuse (18981979) was born and educated in Berlin. In 1934 he left Nazi Germany, and took refuge in the USA, where he taught at Columbia University. He then held appointments at Harvard, Brandeis and the University of California at San Diego. He became well known in the 1960s as the official idealogue of campus revolutions in the USA and Europe. His books include Reason and Revolution (1941) and OneDimensional Man (1964), published by Routledge.

Also published by Routledge:

One-Dimensional Man

Reason and Revolution

The Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse , edited by Douglas Kellner

Volume One, Technology, War and Fascism

Volume Two, Towards a Critical Theory of Society

Volume Three, The New Left and the 1960s

Volume Four, Art and Liberation

Volume Five, Philosophy, Psychoanalysis and Emancipation

Volume Six, Marxism, Revolution and Utopia

EROS AND CIVILIZATION

A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud

Herbert Marcuse

with a preface by

Douglas kellner

First published in England 1956

by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

Ark edition 1987

Transferred to Digital Printing 2005

Reissued with new preface 1998 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

1956 Herbert Marcuse

Preface 1998 Douglas Kellner

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 0-415-18663-3

WRITTEN IN MEMORY OF

SOPHIE MARCUSE

1901-1951

Contents

| 1. |

| Pleasure principle and reality principle |

| Genetic and individual repression |

| "Return of the repressed" in civilization |

| Civilization and want: rationalization of renunciation |

| "Remembrance of things past" as vehicle of liberation |

| 2. |

| The mental apparatus as a dynamic union of opposites |

| Stages in Freud's theory of instincts |

| Common conservative nature of primary instincts |

| Possible supremacy of Nirvana principle |

| Id, ego, superego |

| "Corporealization" of the psyche |

| Reactionary character of superego |

| Evaluation of Freud's basic conception |

| Analysis of the interpretation of history in Freud's psychology |

| Distinction between repressionand "surplus-repression" |

| Alienated labor and the performance principle |

| Organization of sexuality: taboos on pleasure |

| Organization of destruction instincts |

| Fatal dialectic of civilization |

| 3. |

| "Archaic heritage" of the individual ego |

| Individual and group psychology |

| The primal horde: rebellion and restoration of domination |

| Dual content of the senseof guilt |

| Return of the repressed in religion |

| The failure of revolution |

| Changes in father-images and mother-images |

| 4. |

| Need for strengthened defense against destruction |

| Civilization's demand for sublimation (desexualization) |

| Weakening of Eros (life instincts); release of destructiveness |

| Progress in productivity and progress in domination |

| Intensified controls in industrialcivilization |

| Decline of struggle with the father |

| Depersonalization of superego, shrinking of ego |

| Completion of alienation |

| Disintegration of the established reality principle |

| 5. |

| Freud's theory of civilization in the tradition of Western philosophy |

| Ego as aggressive and transcending subject |

| Logos as logic of domination |

| Philosophical protest against logic of domination |

| Beingand becoming: permanence versus transcendence |

| The eternal return in Aristotle, Hegel, Nietzsche |

| Eros as essence of being |

| 6. |

| Obsolescence of scarcity and domination |

| Hypothesis of a new reality principle |

| The instinctual dynamic toward non-repressive civilization |

| Problem of verifying the hypothesis |

| 7. |

| Phantasy versus reason |

| Preservation of the "archaic past" |

| Truth value of phantasy |

| The image of life without repression and anxiety |

| Possibility of real freedom in a mature civilization |

| Need for a redefinition of progress |

| 8. |

| Archetypes of human existence under non-repressive civilization |

| Orpheus and Narcissus versus Prometheus |

| Mythological struggle of Eros againstthe tyranny of reason - against death |

| Reconciliation of man and nature in sensuous culture |

| 9. |

| Aesthetics as the science of sensuousness |

| Reconciliation between pleasure and freedom, instinct and morality |

| Aesthetic theories of Baumgarten, Kant, and Schiller |

| Elements of a non-repressive culture |

| Transformation of work into play |

| 10. |

| The abolition of domination |

| Effect on the sex instincts |

| "Self-sublimation" of sexuality into Eros |

| Repressive versus free sublimation |

| Emergence of non-repressive societal relationships |

| Work as the free play of human faculties |

| Possibility of libidinous work relations |

| 11. |

| The new idea of reason: rationality of gratification |

| Libidinous morality |

| The struggle against the flux of time |

| Change in the relation between Eros and death instinct |

Preface to 1998 Edition

Douglas Kellner

Herbert Marcuses Eros and Civilization (EC) provides an exciting and compelling articulation of his perspectives on contemporary civilization, domination, and liberation. Written at the height of McCarthyism in the 1950s, Marcuses epic of emancipation sketches out his vision of a free and non-repressive civilization during a historical epoch characterized by social repression and attacks on radical thought. His emphasis on liberation, play, love, and eros anticipated the ethos of the 1960s counterculture which in turn made him a guru of radical thought. In addition, the text provides an extremely radical critique of contemporary civilization which was to make Marcuse a darling of the New Left and one of the most influential thinkers of his epoch.

From the perspective of critical social theory, Marcuse reconstructs Freudian and Marxian theories in order to develop a critical theory of contemporary society, combined with visions of a non-repressive society which draws on Marx, Freud, utopian socialism, German idealism, and various poets and philosophers. In this text, Marcuses project went well beyond classical Marxism to envisage new possibilities for liberation in an era when revolutionary action and even critical thinking were threatened by oppressive social forces and conformist ideologies. In his resolutely utopian work, Marcuse articulates the vision of human emancipation that was to distinguish his version of critical theory. Whereas Adorno, Horkheimer, and most other Institute members were reluctant to develop any detailed utopian concepts, or outlines, of an alternative society, Marcuse attempted to sketch out Utopian alternatives to the present way of life. The addition of eros, art, and emancipation to his Hegelian Marxist theory provided new substance to Marcuses thought and eventually was to attract a large audience for his critical theory.