LONDON, NEW YORK, MUNICH,

MELBOURNE, DELHI

First American Edition, 2013

Published in the United States

by DK Publishing,

345 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014

ISBN 978-1-4654-0842-6

This digital edition published in 2013 by DK Publishing

eISBN 9781465419484

Senior Editor: Angela Wilkes

Senior Art Editor: Michael Duffy

US Senior Editor: Margaret Parrish

Editors: Andy Szudek, Hugo Wilkinson, Georgina Palffy, Victoria Pyke, Anna Fischel

Editorial Consultant: Martyn Page

Designers: Mark Lloyd, Jane Ewart

Picture research: Luped Media Research

Jacket Designer: Laura Brim

Jacket Editor: Manisha Majithia

Jacket Design Manager: Sophia M.T.T.

Producer, Pre-production: Lucy Sims

Production Controller: Mandy Inness

Managing Editor: Stephanie Farrow

Senior Managing Art Editor: Lee Griffiths

Publisher: Andrew Macintyre

Art Director: Phil Ormerod

Associate Publishing Director: Liz Wheeler

Publishing Director: Jonathan Metcalf

DK DELHI CREATIVE TEAM

Editor: Rupa Rao

Art Editor: Priyanka Singh

Assistant Editor: Sonia Yooshing

Deputy Managing Editor: Kingshuk Ghoshal

Deputy Managing Art Editor: Govind Mittal

DIGITAL PRODUCTION TEAM

Digital Producer: Linda Zacharia

Head of Technical Development: Roz Hitchcock

Head of Digital Media, Delhi: Manjari Hooda

Senior Editorial Manager: Lakshmi Rao

Digital Graphics Design Manager: Nain Rawat

Producer: Rahul Kumar

Software Engineer: Paranpreet Singh

Assistant Graphics Designer: Rahul Rai

Operations Coordinator: Jalaj Bansal

Digital conversion by DK Digital Production, London and DK Digital Media, Delhi

Copyright 2013 Dorling Kindersley Limited

All rights reserved. No part of this eBook may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owners.

Discover more at www.dk.com

Introduction

W hat is a doctor? In ancient Egypt, healing was the perogative of sorcerers, while in early Greece doctors were considered itinerant curiosities more likely to harm than help. By the 16th century, innovative doctors were practicing an eclectic mix of medicine, alchemy, astrology, herbalism, mineralogy, psychotherapy, and faith-healing, while in the modern world medicine has evolved to make it possible for doctors to operate on patients remotely from another continent.

Today, there is a complex array of scanning and imaging options with which to view the inside of the body, but in ancient Egypt such information would have been deemed utterly irrelevant: examining the patient was unheard of at a time when illness was considered to be the work of the gods. Hippocrates, who practiced in ancient Greece and was considered by many to be the father of modern medicine, found himself imprisoned for many years when he rejected the idea that illness was the whim of deities. Yet by the time he died, he had revolutionized the practice of medicine and established the basic foundations of the role of the physician.

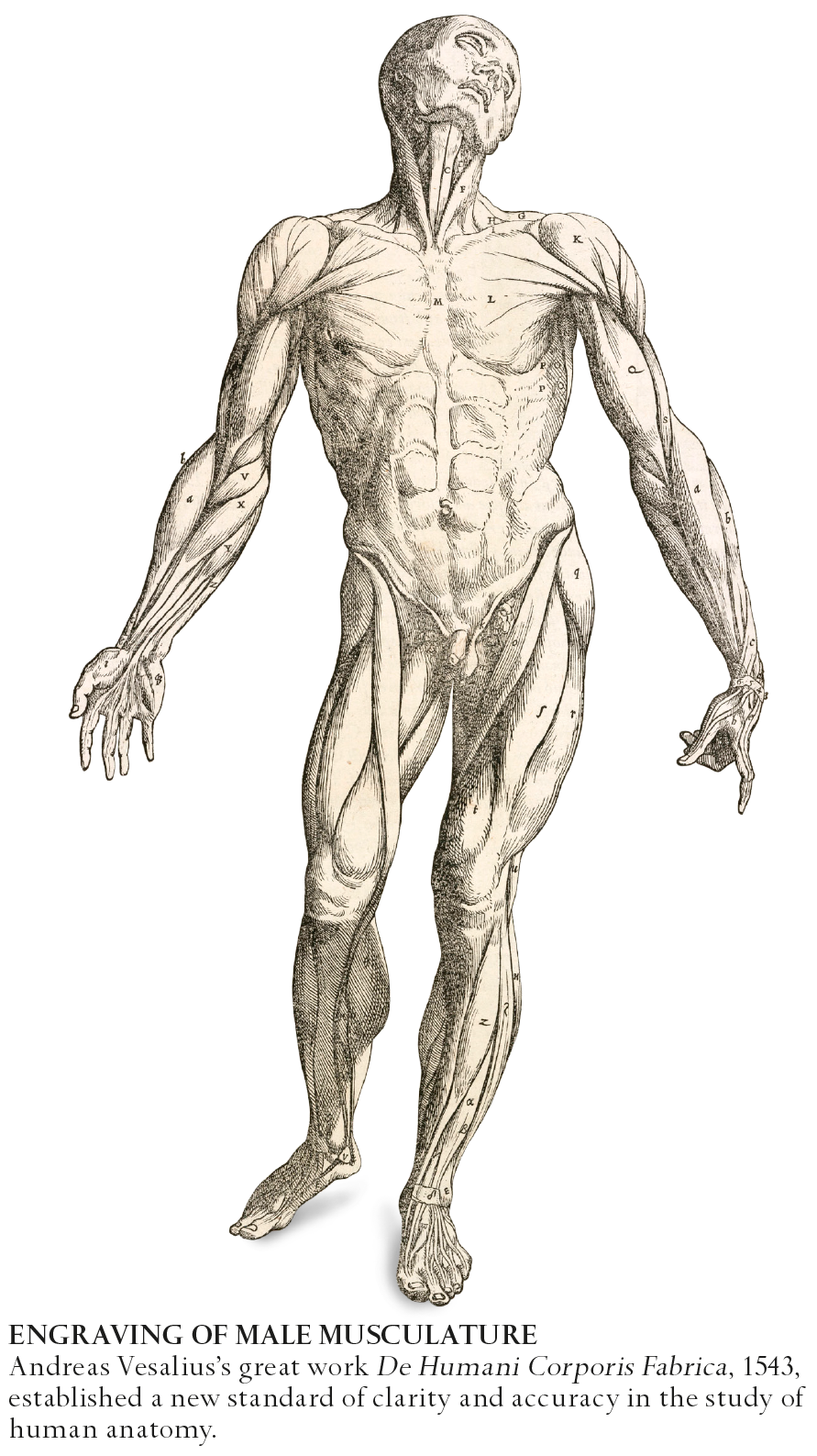

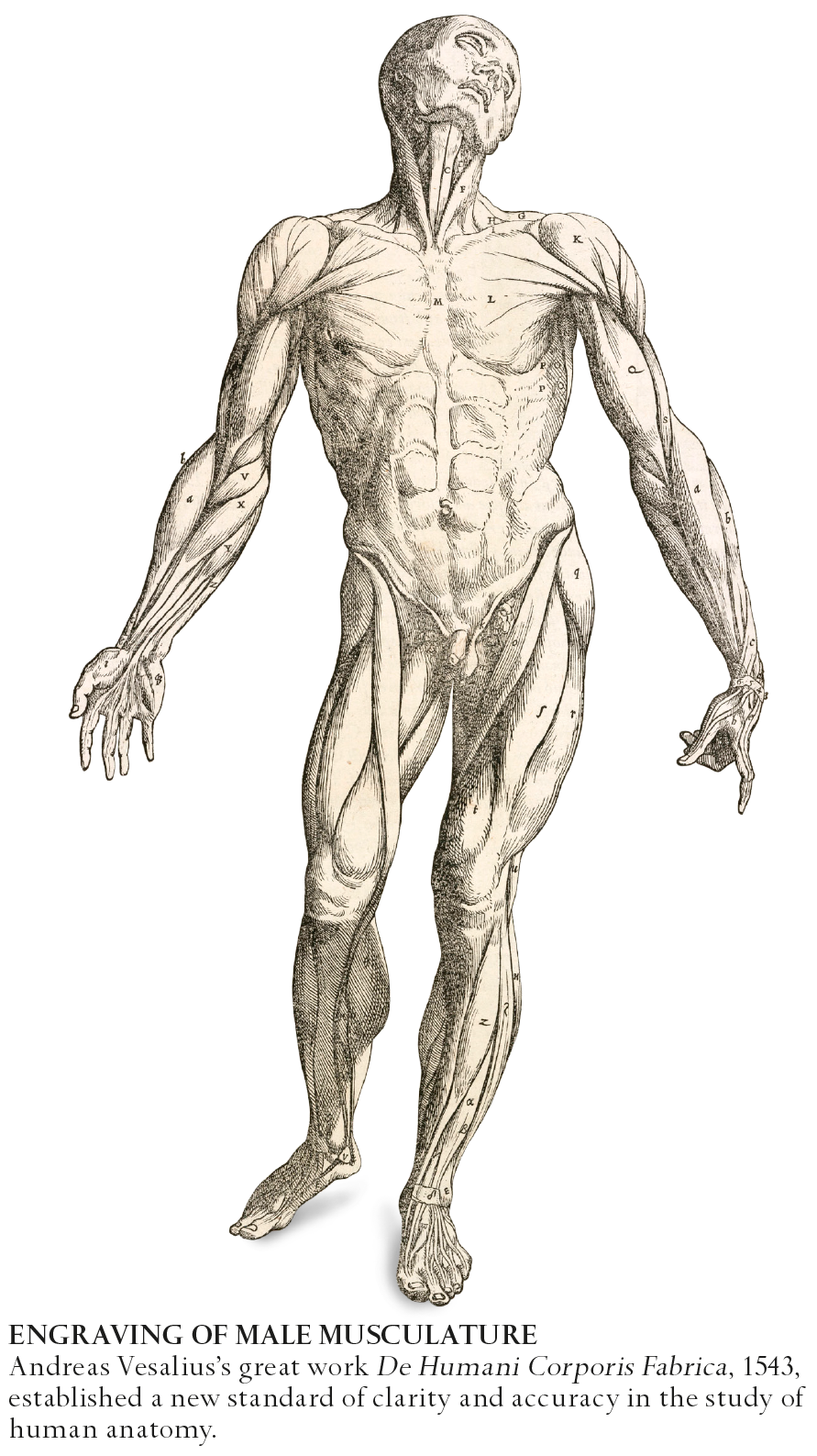

Many others contributed, of courseImhotep of Egypt, Chakara in India, Galen in Rome, and Zhang Zhongjing of China in ancient times. Islams medieval Golden Age boasted Al-Rhazi and Ibn Sina (Avicenna), and the Renaissance had anatomist Andreas Vesalius and the groundbreaking Paracelsus, who founded many of the principles of modern medicine. All these figures contributed to medicine, often in ways that challenged the conventional views of the time.

Of course, there were many wildly inaccurate theories, and someto our eyesoutlandish remedies, from boiled newborn puppies to the ashes of a burned swallow (used to cure hirsuitism). So popular was bloodletting by leech that at one point doctors were actually known as leeches. And so established were Galens theories on human anatomy that for centuries, no one questioned the fact that his findings had been gathered by dissecting the bodies of dogs and monkeys, rather than humans. Alongside the more spectacular medicines, however, were herbs and minerals that to this day form the basis of tried-and-tested drug cures, and in among the quacks and charlatans were many diligent and painstaking innovators.

Rigorous observation and detailed detective work have played a huge part in the development of medicine. Before English physician William Harvey published his momentous book on the heart and circulation in 1628, for example, he spent over 20 years dissecting and experimenting on the pulsing hearts of thousands of animals from more than 60 species. Building on concepts and evidence dating back to ancient times, Harvey also wove theory and practice into a scientifically sound, evidence-based description of the circulatory system. Armed with this knowledge, physicians were able to make major improvements in the way they diagnosed and treated disease. There are, of course, famous instances where chance has also played an important role. Had the weather not been unseasonably cold when Scottish medical researcher Alexander Fleming left his messy laboratory to go on vacation, for example, he might not have discovered penicillin, which has since prevented immeasurable suffering and saved countless lives. It took the stimulus of World War II, however, to fully realize the potential of this, the first antibiotic.

War and conflict have given impetus to many branches of medicine, acting as a catalyst for innovation and learning. One of the earliest medical documents, the 3,600-year-old Smith Papyrus of ancient Egypt, describes treatment of wounds probably sustained on the battlefield; in ancient Rome, gladiators injuries provided valuable medical insight at a time when human dissection was forbidden. In the 16th century, French army surgeon Ambroise Par used innovative procedures, such as poultices and ligatures, that then filtered from the battlefield through to general surgery. Another French surgeon, Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, pioneered the use of ambulances and triage in the 19th century. During World War I, doctors noted that mustard gas affected fast-multiplying cells in the body, which ultimately led to the development of anti-cancer chemotherapy drugs. Medicine even benefited from the most deadly weapon of all, the atomic bomb: its effects indirectly led to bone marrow transplants and one of medicines newest areas of researchstem cell therapy.

The journey made by the science of medicine is an astonishing one. Today we take for granted our modern operating rooms with their rigorously germ-free environments and sterilized equipment, but it is worth remembering that the notion of germs as transmittors of infection has only existed since the 19th century. It is also hard to imagine that there was a surprising amount of surgery already taking place millennia ago: holes were being drilled in patients heads from prehistoric times through to the 18th century, for example. And while in ancient Greece it was rare for the skin to be deliberately broken, surgeons in ancient Rome developed tools, equipment, and procedures not dissimilar to those in use today. However, modern surgery is also making use of robots, lasers, and mind-boggling technology. Just as we struggle to imagine prehistoric brain surgery, it is equally hard to imagine just how much has been achieved by modern medicine. It has waged war on age-old killers such as cholera, smallpox, and tuberculosis, decoded our DNA, mapped the human genome, and created the potential for nanotechnology and tissue-engineering. The future ambition for medicine is phenomenal, but the challenges are not to be underestimated.