THE GOLDEN AGE OF TRAIN TRAVEL

Steve Barry

American tourists of 1910 taking scenic photographs from the rear observation platform of a Union Pacific train.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

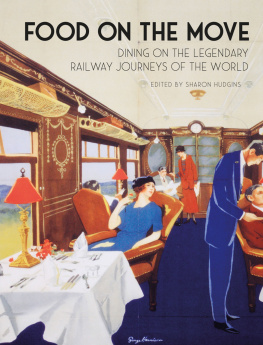

The Orange Blossom Special on the Seaboard Railroad, postcard of late 1940s.

CONTENTS

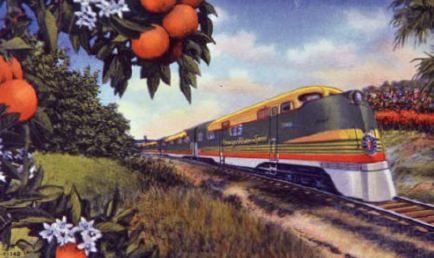

Poster advertising Chicago & Alton Railroad, with route map ingeniously incorporated into reclining chair holding lady with fan, c. 1885. Pullman Palace buffet and sleeping cars were offered en route.

THE RISE OF THE RAILROADS

T HE MOST significant event in North American railroad history took place on May 10, 1869. On that date, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads met at Promontory Summit, Utah, for the driving of the golden spike and the completion of the transcontinental railroad. With just a few blows from a spike maul, east and west were united by twin ribbons of steel. It also marked the day the US railroads moved from adolescence to maturitythey had vanquished the stagecoach and the canalending a mere four decades of whirlwind change. The American Civil War was over, and the nation and its railroads were entering a new era.

The build-up to this golden age is a remarkable story itself. Railroads were well established in Europe by 1830, but were hardly present in the new world. Freight railroads began to appear, tied to specific industries such as mining, but passenger travel remained the domain of the stagecoach and horse. It wasnt until the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O) was chartered in 1827 that the idea of a network of rails began to take shape. The B&O instituted passenger service in 1831 to the suburbs of Baltimoreinitially it was horse drawn, and later steam powered. Railroad mileage in the United States quickly boomed. In 1830 only the B&Os 23 miles was built. By 1840 the mileage had increased to almost 3,000 and by 1850 it tripled to over 9,000 miles. It tripled again by 1860, with over 30,000 miles of track constructed. Due to the Civil War, it would take twenty years for mileage to triple again, with over 92,000 miles built by 1880. Another 100,000 miles would be in use by 1900. Passenger-miles would increase along with the track mileage, surpassing 7 billion by 1865 and reaching 16 billion in 1900.

Early passenger coaches were not much more than horse carriages mounted on flanged wheels. It was the B&Os Ross Winans, one of the great innovators of early railroad design, who came up with the double-truck passenger car. Two sets of four wheels, one set under each end of the car, allowed for longer coaches and smoothed out the ride. By 1840 most railroads had adopted what is still the basic standard design for a rail car. Other changes over the next twenty years included a clerestory roof that allowed additional light in the car and aided in circulating air. As railroad travel became more competitive, the cars became less utilitarian with each railroad embellishing its coaches to attract passengers. By 1855, railroads had reached the point where long-distance travel was possible, and to lure passengers the railroads started adding the first premium carsdiners, observation cars, lounges and more.

Golden Spike ceremony, May 10, 1869, joining the Union Pacific track with the Central Pacific line at Promontory, Utah, thus making transcontinental railroad travel across the US possible for the first time.

Early passenger trains featured no onboard amenities. At meal times trains stopped at stations equipped with dining halls, and passengers stayed in luxurious hotels overnight. Business travelers demanded faster service, though, and one way to achieve that was to keep the trains moving. Sleeping cars had been developed as early as 1830, but it was Theodore T. Woodruff who put the first fleet of cars in service in 1857. Unlike coaches, which were owned by each railroad, sleeping cars were operated by independent companies, as these cars might travel over several different railroads on each journey. Other sleeping-car companies soon entered the market, although most of these companies had a very short life when one dominant company entered the field. Dining cars entered regular service on the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad in 1862, although the food was prepared off the train.

When one thinks of rail travel, especially in the golden age, one does not think of pedestrian coaches, however. One thinks of the palatial first-class accommodations. To find the birth of those, one needs to go back to 1840 on the Camden & Amboy Railroad, when two coaches were equipped not with the standard wooden benches of the time, but with rocking chairs. Seat springs, upholstery and better protection from the outside elements (not only weather, but locomotive soot and sparks) all were part of the earliest first-class services.

That brings us up to that day at Promontory Summit in Utah in 1869. Rail travel was common from east coast cities to Chicago, albeit a bit rough. Most major waterways still had not been bridged, and track gauges still had not been standardized so a long trip still meant changing trains, sometimes involving an overnight stay at the connecting cities.

Directors of the Union Pacific (UP) in a luxurious private rail car during the construction of the railroad in 1868.

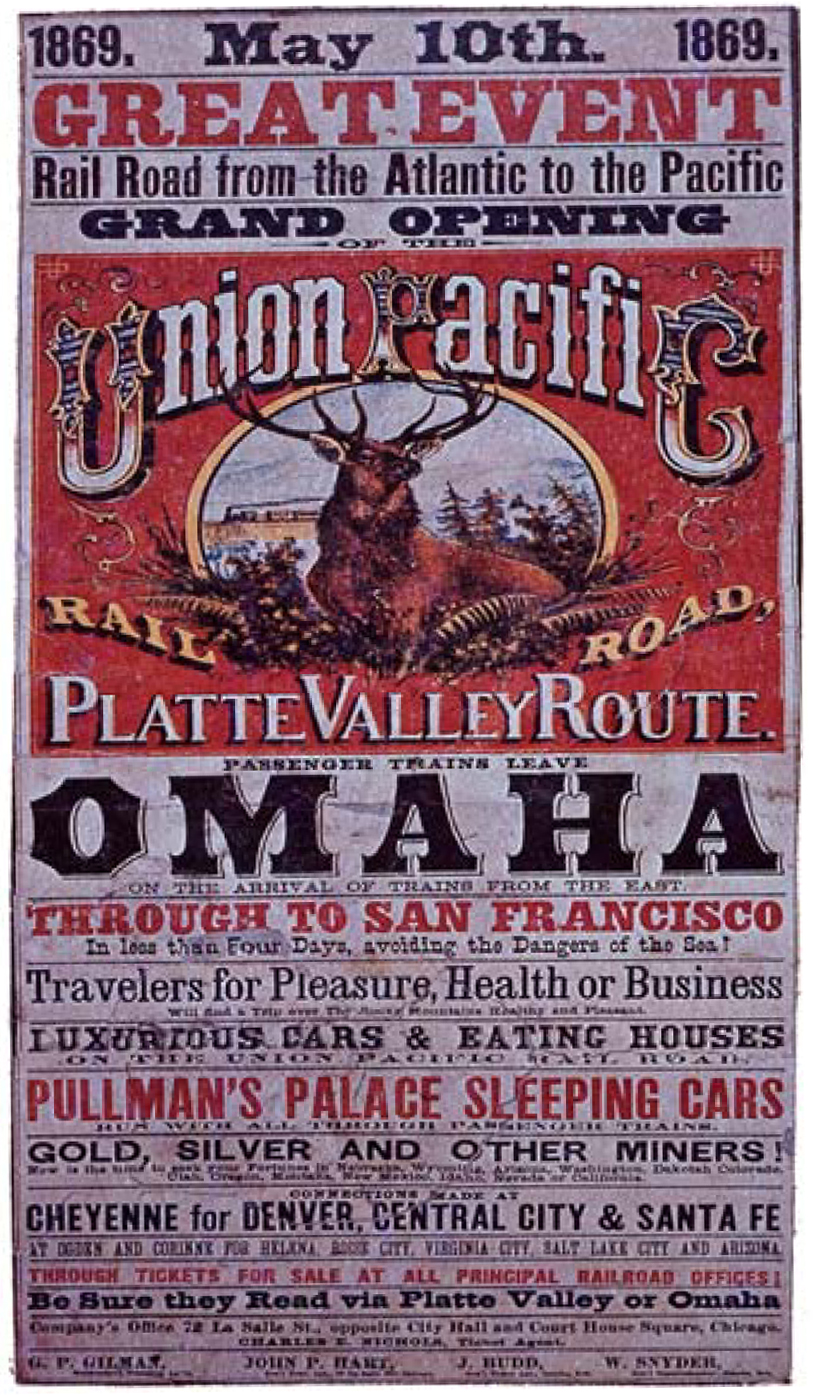

Poster advertising the grand opening of the Union Pacific Railroad route from Omaha to San Francisco in less than four days, avoiding the dangers of the sea!

In the post-Civil War years, passenger car development was still continuing. From the beginning, cars were made from wood, but as the years progressed the materials got finer. Cherry and walnut became standard, although oak was used on some cheaper interior work. The first heated cars appeared around 1870, utilizing piping that brought in steam from the locomotives (and replacing the coal stoves which kept part of the car hot and left other parts cold). Air brakes became standard in the 1870s, dramatically improving safety. Vestibules at each end of the coach were initially open, exposing passengers to the weather and locomotive soot as they passed between cars; closed vestibules became standard by the 1880s.

Meanwhile, the fabric of the nation was changing as well. The mobility provided by the passenger train broke down regional barriers. Business could be more easily conducted between firms that were hundreds of miles apart. Railroad profits grew by leaps and bounds as passenger revenues outdistanced those of freight. And along with the fast passenger trains came a whole new category of businessexpress traffic. News could now spread faster as the magazines and newspapers of the time hitched a ride on the passenger trains.