GREGORY N. FLEMMING

At the Point of a Cutlass

THE PIRATE CAPTURE, BOLD ESCAPE, & LONELY EXILE OF PHILIP ASHTON

ForeEdge

ForeEdge

An imprint of University Press of New England

www.upne.com

2014 Gregory N. Flemming

All rights reserved

For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Suite 250, Lebanon NH 03766; or visit www.upne.com

Cloth ISBN: 978-1-61168-515-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-61168-562-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013954865

And a supplication for our sea-faring people; that they may more generally turn and live unto God; that they may not fall into the hands of pirates; that such as are fallen into their hands, may not fall into their ways; that the poor captives may, with cries to God that shall pierce the heavens, procure His good providence to work for their deliverance; and, that the pirates now infesting the seas may have a remarkable blast from heaven following of them.

COTTON MATHER

Instructions to the Living from the Condition of the Dead (1717)

Contents

Prologue

JULY 19, 1723

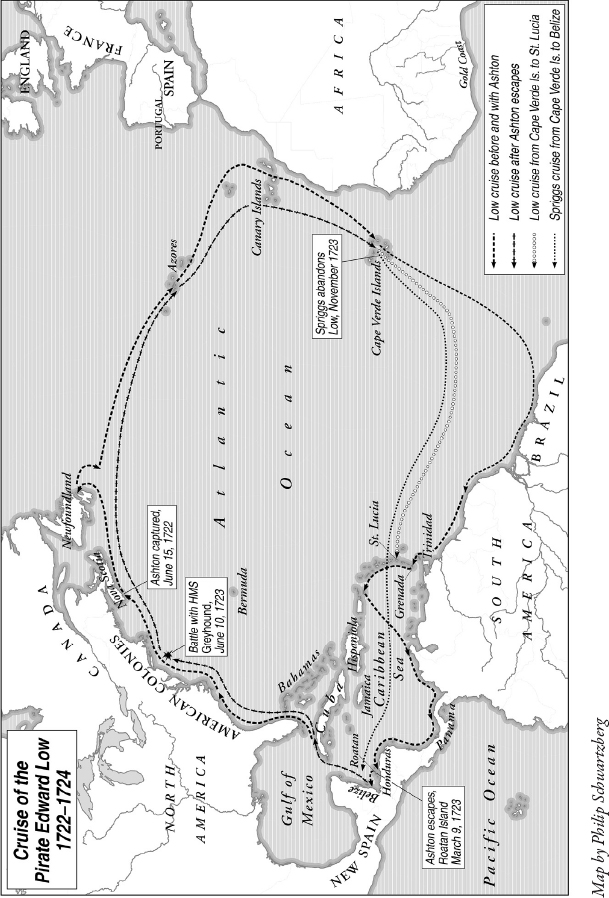

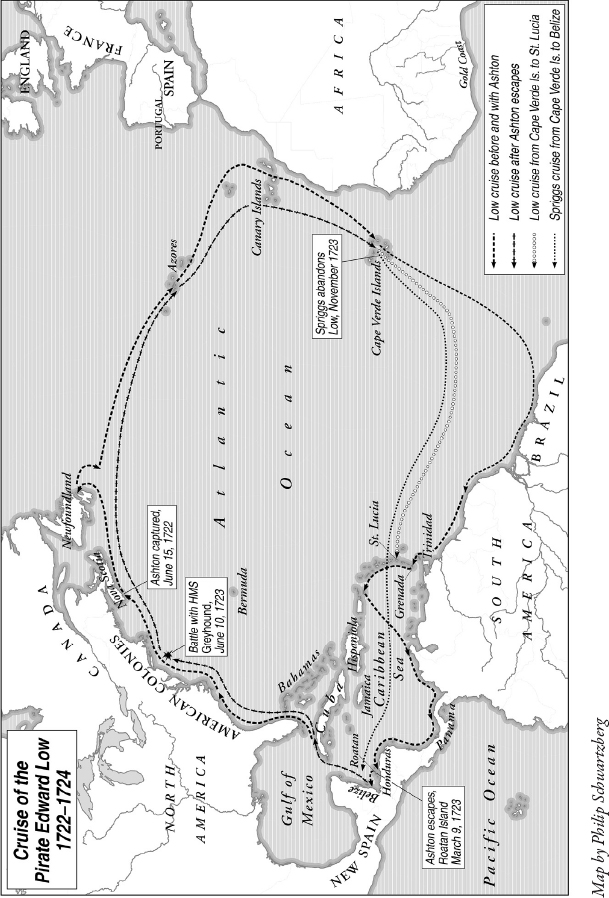

Exactly one week before he died, Joseph Libbey stood in court and pleaded his innocence. Libbey had shown the judges a year-old copy of the Boston News Letter, from July 1722, that contained depositions by the captains of three fishing vessels. Those statements, sworn under oath, attested that Libbey was a forced man. But over the past thirteen months, Joseph Libbey had made enough mistakes for the witnesses who testified in court to claim he was in fact guilty of being an active member of a pirate crew that had been terrorizing the Atlantic coast. Libbey fired guns during the pirates attacks on other ships, the witnesses said. He was a stirring, active man among them and had been seen going aboard captured vessels in search of plunder.

The gallows was erected on the long, narrow bar of sand and rock that formed Gravelly Point, at the edge of the harbor in Newport, Rhode Island. A large crowd of people had come to watch the condemned men dienot only Libbey, but twenty-five others accused of being pirates. Libbey was one of the youngest of the men, just twenty-one or twenty-two years old that summer. Before his capture he had been a fisherman from the small village of Marblehead, Massachusetts, where he had grown up. Like some of the other men who stood with him at the gallows, Libbey claimed he was the victim of cruel circumstances. He had not chosen to sail with the pirates; he and many of the others had, in one captives words, gone with the greatest reluctancy and horror of mind and conscience. In time, however, Joseph Libbey must have given in to the crews brutalitythe threats, whippings, and beatingsand began helping out when the pirates attacked other vessels at sea.

The execution was held shortly after noon on Friday, July 19, 1723. A local minister, Nathaniel Clap, said a final prayer. After that, it was time. Libbey stood on the gallows while a rope was placed around his neck, the thick knot of the noose positioned to the side of his head, under the ear, which was thought to be the most effective placement. When the bodies of the convicted pirates dropped, the ropes snapped tightbut only a few of the twenty-six men died instantly. The rest strangled for a minute or two longer, convulsing and gasping for air as they swung from the ropes. The crowd stood watching the morbid spectacle unfold. The eyes of the men bulged from their heads as they hanged, their lips slowly turning purple. Oh! a witness wrote afterwards. How awful the noise of their dying moans. Finally, the ropes gripping the mens necks cut off the supply of blood to their brains and the flow of air to their lungs, and they died. When the sun set on Newport that day, the spectators had witnessed history, one of the largest mass executions ever held in the nearly two hundred years of the American colonial era.

Two thousand miles away from New England on that summer day, another young man was sitting alone on the ground, surrounded not by a crowd of spectators but by utter solitude. He gazed out at the empty blue sea from a small cay that was no more than a few hundred yards off a remote island at the western edge of the Caribbean. The island had once, long ago, been inhabited by native people, and again later by a small group of British colonists who tried to build a plantation there but failed and left after just a few years. By 1723, the island was wild and desolate, overgrown and uninhabited for the past seventy-five years.

The man who was stranded along its quiet, windswept shore was named Philip Ashton. Four months earlier, Ashton had run for his life into the thick, jungle-like woods of the island when his ship stopped there for repairs and fresh water. Now Ashton was completely alone, and the odds of survival were against him. He had no knife, no gun, and no way to make a fire. He was hungry and growing weaker by the day. He hadnt eaten a cooked meal since hed escaped on the island and was barely surviving on whatever fruit he could find growing on trees and the raw turtle eggs he could dig out of the sand. Everything, Ashton later recorded, looked with a dismal face. Ashtons condition would continue to worsen and within a matter of months, Ashton would be so starved and sick that he would be close to death.

These two menJoseph Libbey and Philip Ashtonwere friends. They had worked together on the same fishing schooner that sailed out of the village of Marblehead in what was then the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Less than a year earlier, Libbey had reached his hand over the side of a boat and saved Ashton from drowning. They had been together on one of the most terrifying nights of their lives, a quiet Friday evening in June 1722, when Ashton and Libbey were attacked and forced to go aboard the pirate ship. They came face-to-face with a raving-mad pirate captain, Edward Low, who captured more ships and killed more people than even Blackbeardoften by hacking the lips or ears off his victims or slaughtering them and roasting their hearts over a fire. It was during their cruise with the pirates across the Atlantic and back that Ashton and Libbey parted ways. By the end of July 1723, Joseph Libbey had been accused of being a member of the vicious pirate crew, and was dead. Philip Ashton was trying to figure out how to survive.

Behind the tragedy of this summer day lies the incredible true story of Philip Ashtonhis capture, his escape, his survival, and his rescue. Ashton has been called Americas real-life Robinson Crusoe, and in many ways he would go on to become one of historys most noteworthy pirate captives. Today there are no statues of Philip Ashton nor any memorials hidden away in his hometown, the small seaside community of Marblehead, Massachusetts. Ashton does not even have a cemetery headstone, since he more than likely died at sea. No one ever painted a portrait of Ashton, so there is no surviving record of what he looked like. But he did leave an account of his ordeal, and during his lifetime, his incredible story amounted to what in modern times would be termed a bestseller. Ashtons narrative describing his voyage with the pirates and his survival on an uninhabited island is a rare first-person account of a pirate captive and castaway in the early 1720s, when Atlantic piracy was an ever-present threat to men who worked at sea. Copies of the book were published in both America and Europe and may even have been read by the very man who had just written the novel about Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe.