Contents

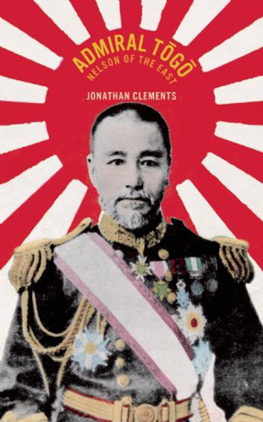

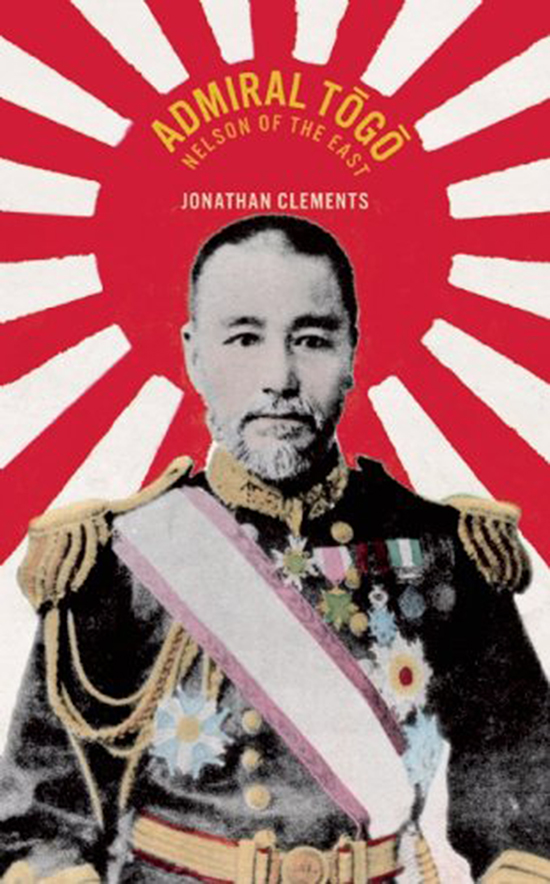

Admiral Tg: Nelson of the East

ALSO BY JONATHAN CLEMENTS

AND AVAILABLE FROM HAUS PUBLISHING

IN THE MAKERS OF THE MODERN WORLD SERIES

Wellington Koo: China

Prince Saionji: Japan

IN THE LIFE & TIMES SERIES

Marco Polo

Mao

Mannerheim: President, Soldier, Spy

Admiral Tg:

Nelson of the East

Jonathan Clements

Haus Publishing

London

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by

Haus Publishing Ltd

70 Cadogan Place

London SW1X 9AH

www.hauspublishing.com

Copyright Muramasa Industries, 2010

The moral right of the author has been asserted

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-906598-62-4

Typeset in Warnock by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by JF Print, Sparkford

CONDITIONS OF SALE

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

For Stephen Jones

Introduction

I n 1996, during a British parliamentary debate on the selling of naval assets to a Japanese consortium, an MP alluded to the awful prospect that a road on former Admiralty property might be renamed Admiral Tg Avenue. It was assumed by both speaker and audience that this would be a bad thing a strange and inadvertent reversal of fortune for a naval commander who had once been so feted by the British establishment. Nobody pointed out the irony that the same Admiral Tg had been trained by the British, that he had held that rank for a 20-year period when Japan and Britain were allies, or that his presence was already stamped on British road maps, in the form of Mikasa Street in Barrow-in-Furness, named after his flagship. Once hailed as a world-class hero, Admiral Tgs reputation was sunk in the afterlife, consumed in the maelstrom of war crimes by others. Six decades after his death, he was simply assumed to have been Britains enemy.

Tg Heihachirs military career began in the last days of the samurai, when Japans self-imposed exclusion was smashed apart by Western powers in search of trade concessions. He became a member of what would become the Japanese navy during the brief civil war that constituted the Meiji Restoration, in which he was a low-ranking samurai in just one of several factions, all claiming to be loyalists. Luckily for Tg, his faction was victorious, and thereby able to impose its concept of loyalty on the rest of Japan a loyalty that favoured the abolition of the Shgunate, the restoration of power to the Emperor himself and the modernisation of Japan to meet the challenge from the West. It was as part of this modernisation that Tg was sent to learn from the British he studied for seven years in England, to the extent that his later victories were often misleadingly claimed by British newspapers to be the accomplishments of a local hero, in imitation of a British icon.

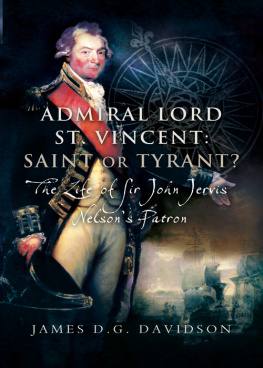

It is considered condescending today to attach associations of one culture to that of another. Calling Tg the Nelson of the East implies by some token that he is merely a mimic of a European predecessor, a pale shadow of a true hero. However, Tgs interest in Horatio Nelson was a much-recorded feature of his own time, and so I have retained the sobriquet that was so often heaped upon him in the early 20th century, including: Nelson of Japan (Western Mail), Nelson of the East (Glasgow Herald), Nelson of Japan (New York Truth), Nelson of the East (Newcastle Chronicle), Nelson of the East (South Mail), best compared with Nelson (New York Tribune), and modern naval officers should find it more helpful to study tactics of Tg than those of Nelson (New York Sun). Indeed, the concept was soon embraced by the Japanese themselves, who never seemed to tire of styling themselves as the British of Asia, or comparing Tg to the victorious admiral of Trafalgar. Nelson was Tgs hero, a figure who inspired him during his student days in England, and whose Trafalgar tactics he adapted at Tsushima. In the Song of Condolence composed to mark Tgs funeral, the poet Doi Bansui defiantly reversed the clich, instead referring to Nelson as the Tg of England.

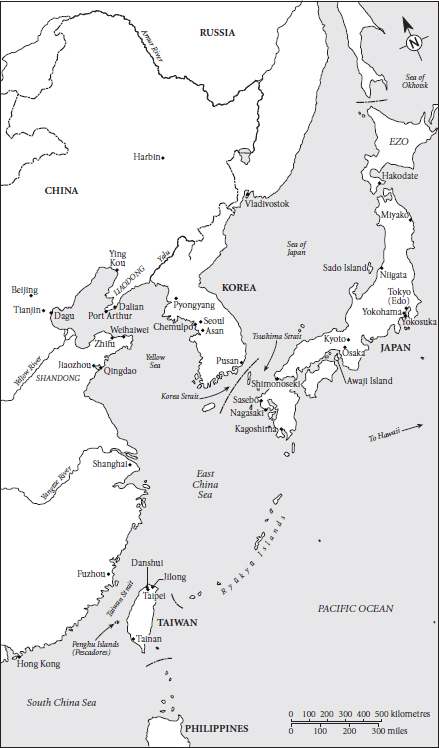

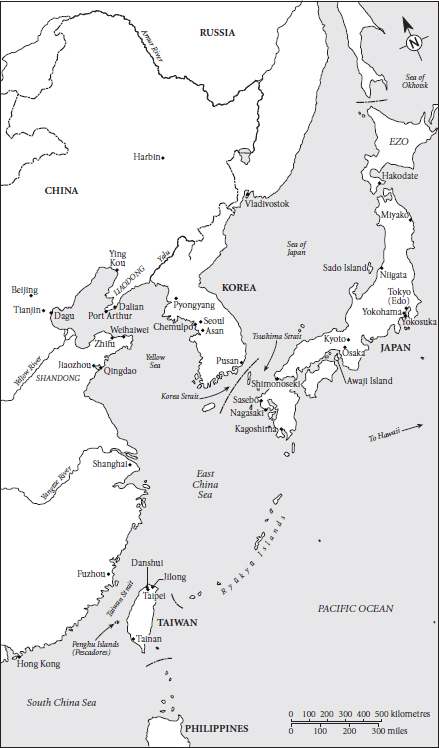

Tg was witness to the bloody birth-pangs of modern Japan, and one of the victors in the conflict that toppled the short-lived breakaway Republic of Ezo. While some of his countrymen, and even family-members, clung to the old order, Tg embraced the new, abandoning his clan allegiances to become one of the first officers of the national navy. He was, fortunately for him, posted abroad in the 1870s, and hence was not dragged into the counter-revolutionary Satsuma Rebellion, which saw the death of his brother and many of his old clan colleagues in a protest against the end of samurai traditions. He is remembered chiefly for his command of Japanese fleets as a high-ranking officer approaching retirement, but the groundwork for his achievements was undoubtedly laid during the long years of peace, when a younger Tg gained a reputation as an expert, or even something of a stickler, on the subject of maritime law. His grasp of naval etiquette and protocol was no idle occupation, but allowed him to maintain active service even during long stretches bedridden with illness. It also kept the young captain from making hot-headed decisions during tense stand-offs that could have ruined a less careful sailors career. Crucially, it gave him the incisive intellectual tools to deal with the thorniest problem he ever faced: the no-win situation in the Yellow Sea in 1894, when he was confronted by mutinous Chinese soldiers aboard the British-registered transport ship Kowshing.

Tg was closely associated with the transformation of Japanese sea power and its first relations with the Western world. As a teenager, he saw samurai standing waist-deep in water, angrily brandishing their swords at distant British warships. He witnessed the last gasp of old-school abordage, as sword-wielding marines braved a deck-mounted machine gun to leap aboard one of the first ironclads. After decades with barely a shot fired in naval combat, or overwhelming broadsides by European ships against hopelessly outclassed native boats, Tg was a participant in the first battle to pit modern naval technology against itself. The Battle of the Yalu set the German-built battleships of the Chinese navy against the British-built cruisers of Japan, a generation before the First World War. Most famously, Tg was the admiral who led the Japanese navy to a resounding, crushing victory against two fleets from the Tsars Russia, the first time that an Asian nation had bested a modern European power.

In later life he was a reluctant celebrity, embraced by the Japanese as a man whose sense of duty placed him above party politics, and feted by the wider world as an invincible admiral. His fame seems odd today because he was far from charismatic. His nickname among his men, Oni (The Devil), may even have been a facetious, sarcastic sass a terrifying name for a commander who was actually rather quiet and unassuming. Throughout his life his associates described him as quiet, dedicated and stubborn, but also as workmanlike. Tgs genius lay in training, in operational ideas, in strategic thinking. His great victory at Tsushima was arguably won not at sea in 1905, but in the drills and intelligence-gathering of the preceding two years. He is certainly not the kind of man who would become a celebrity today: he was not a creature of soundbites, nor did he cut a conspicuous figure in a crowd. And yet, Tg was the first Japanese subject to grace the cover of