Sword Song

The Battle for London

Bernard Cornwell

Contents

Part One

The Bride

Part Two

The City

Part Three

The Scouring

Sword Song is voor Aukje,

met liefde:

Er was eens

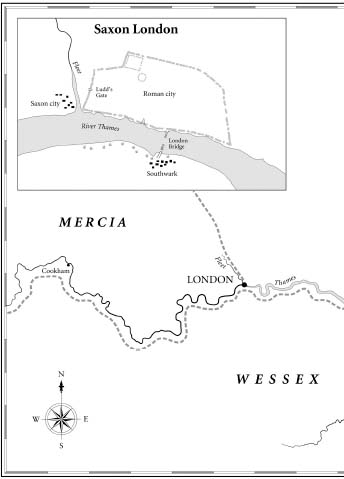

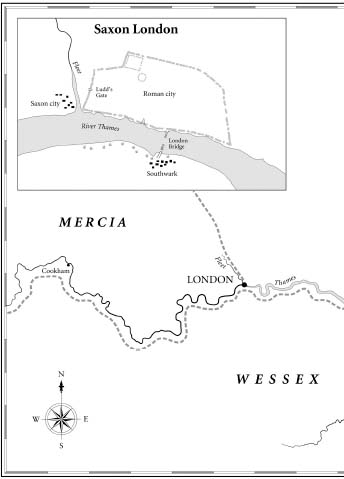

T he spelling of place-names in Anglo-Saxon England was an uncertain business, with no consistency and no agreement even about the name itself. Thus London was variously rendered as Lundonia, Lundenberg, Lundenne, Lundene, Lundenwic, Lundenceaster, and Lundres. Doubtless some readers will prefer other versions of the names listed below, but I have usually employed whichever spelling is cited in either the Oxford or the Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names for the years nearest or contained within Alfreds reign, AD 871899, but even that solution is not foolproof. Hayling Island, in 956, was written as both Heilincigae and Hglingaigg. Nor have I been consistent myself; I spell England as Englaland, but have preferred the modern form Northumbria to Norhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.

scengum | Eashing, Surrey |

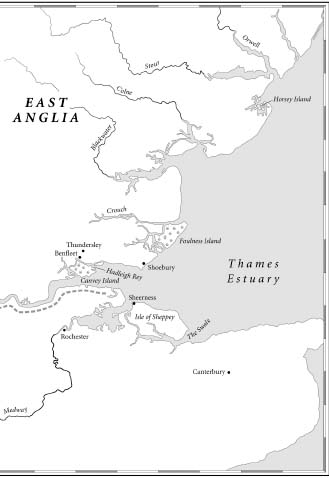

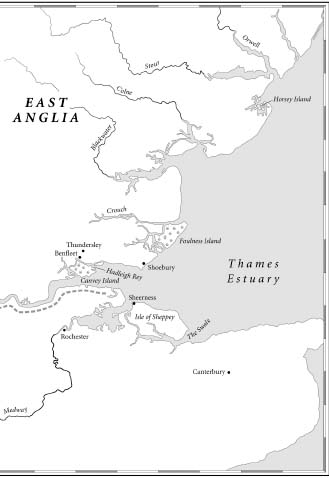

Arwan | River Orwell, Suffolk |

Beamfleot | Benfleet, Essex |

Bebbanburg | Bamburgh, Northumberland |

Berrocscire | Berkshire |

Cair Ligualid | Carlisle, Cumbria |

Caninga | Canvey Island, Essex |

Cent | Kent |

Cippanhamm | Chippenham, Wiltshire |

Cirrenceastre | Cirencester, Gloucestershire |

Cisseceastre | Chichester, Sussex |

Coccham | Cookham, Berkshire |

Colaun, River | River Colne, Essex |

Contwaraburg | Canterbury, Kent |

Cornwalum | Cornwall |

Cracgelad | Cricklade, Wiltshire |

Dunastopol | Dunstable (Roman name Durocobrivis), Bedfordshire |

Dunholm | Durham, County Durham |

Eoferwic | York, Yorkshire |

Ethandun | Edington, Wiltshire |

Exanceaster | Exeter, Devon |

Fleot | River Fleet, London |

Frankia | Germany |

Fughelness | Foulness Island, Essex |

Grantaceaster | Cambridge, Cambridgeshire |

Gyruum | Jarrow, County Durham |

Hastengas | Hastings, Sussex |

Horseg | Horsey Island, Essex |

Hothlege | River Hadleigh, Essex |

Hrofeceastre | Rochester, Kent |

Hwealf | River Crouch, Essex |

Lundene | London |

Mides Stana | Maidstone, Kent |

Medwg | River Medway, Kent |

Oxnaforda | Oxford, Oxfordshire |

Padintune | Paddington, Greater London |

Pant | River Blackwater, Essex |

Scaepege | Isle of Sheppey, Kent |

Sceaftes Eye | Sashes Island (at Coccham) |

Sceobyrig | Shoebury, Essex |

Scerhnesse | Sheerness, Kent |

Sture | River Stour, Essex |

Sutherge | Surrey |

Suthriganaweorc | Southwark, Greater London |

Swealwe | River Swale, Kent |

Temes | River Thames |

Thunresleam | Thundersley, Essex |

Wced | Watchet, Somerset |

Wclingastrt | Watling Street |

Welengaford | Wallingford, Oxfordshire |

Werham | Wareham, Dorset |

Wiltunscir | Wiltshire |

Wintanceaster | Winchester, Hampshire |

Woccas Dun | South Ockenden, Essex |

Wodenes Eye | Odney Island (at Coccham) |

D arkness. Winter. A night of frost and no moon.

We floated on the River Temes, and beyond the boats high bow I could see the stars reflected on the shimmering water. The river was in spate as melted snow fed it from countless hills. The winterbournes were flowing from the chalk uplands of Wessex. In summer those streams would be dry, but now they foamed down the long green hills and filled the river and flowed to the distant sea.

Our boat, which had no name, lay close to the Wessex bank. North across the river lay Mercia. Our bows pointed upstream. We were hidden beneath the leafless, bending branches of three willow trees, held there against the current by a leather mooring rope tied to one of those branches.

There were thirty-eight of us in that nameless boat, which was a trading ship that worked the upper reaches of the Temes. The ships master was called Ralla and he stood beside me with one hand on the steering-oar. I could hardly see him in the darkness, but knew he wore a leather jerkin and had a sword at his side. The rest of us were in leather and mail, had helmets, and carried shields, axes, swords, or spears. Tonight we would kill.

Sihtric, my servant, squatted beside me and stroked a whetstone along the blade of his short-sword. She says she loves me, he told me.

Of course she says that, I said.

He paused, and when he spoke again his voice had brightened, as though he had been encouraged by my words. And I must be nineteen by now, lord! Maybe even twenty?

Eighteen? I suggested.

I could have been married four years ago, lord!

We spoke almost in whispers. The night was full of noises. The water rippled, the bare branches clattered in the wind, a night creature splashed into the river, a vixen howled like a dying soul, and somewhere an owl hooted. The boat creaked. Sihtrics stone hissed and scraped on the steel. A shield thumped against a rowers bench. I dared not speak louder, despite the nights noises, because the enemy ship was upstream of us and the men who had gone ashore from that ship would have left sentries on board. Those sentries might have seen us as we slipped downstream on the Mercian bank, but by now they would surely have thought we were long gone toward Lundene.

But why marry a whore? I asked Sihtric.

Shes Sihtric began.

Shes old, I snarled, maybe thirty. And shes addled. Ealhswith only has to see a man and her thighs fly apart! If you lined up every man whod tupped that whore youd have an army big enough to conquer all Britain. Beside me Ralla sniggered. Youd be in that army, Ralla? I asked.