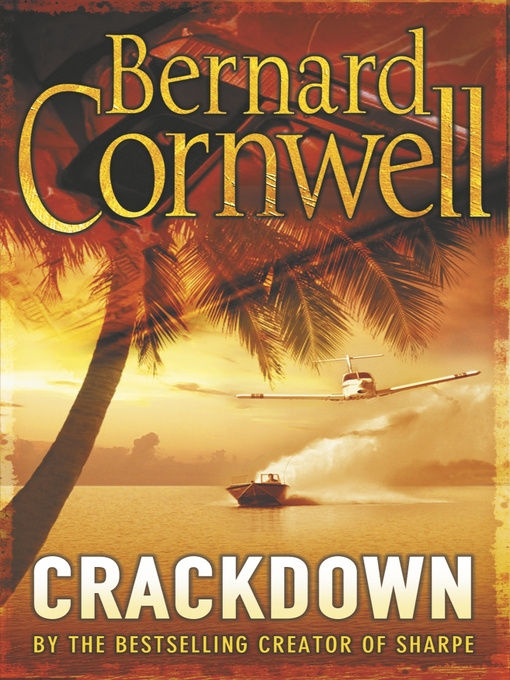

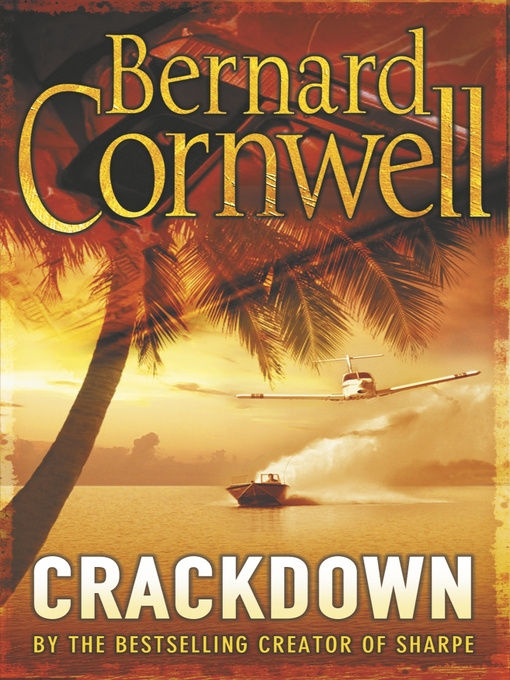

Crackdown

by Bernard Cornwell

Acknowledgements and Dedication

It is usual, and prudent, to claim that no characters in any novel are based on real people, which claim is certainly true of the characters in Crackdown, yet the fictional island of Murder Cay is based on the all too real Bahamian island of Normans Cay, and for details of that island, as well as for much other information about the narcotraficantes, I am indebted to the book The Cocaine Wars by Paul Eddy, Hugo Sabogal and Sara Walden.

I must also acknowledge my extreme debt to Dr Laura Reid, erstwhile Medical Director of the Gosnold Treatment Center in Falmouth, Cape Cod, who educated me about cocaine, and about the difficulties faced by her patients who are trying to break their cocaine addictions.

It seems to me that the true warriors of the drug war are people like Laura Reid and her colleagues whose battles and victories are rarely headlined. To them, and to all their patients who have defeated the evil, Crackdown is respectfully dedicated.

You cannot cheat death. It is not an illusion. It does not melt into air, into thin air, it is instead a clumsy thing of the night, to be discovered in the dawn.

And it was in the dawn, in a gentle Bahamian dawn, that I discovered Hirondelle.

She had been a cruising yacht; a pretty thirty-eight-foot fibreglass sloop. She had been a graceful thing, and she had been butchered.

When I found Hirondelle she was nothing but a barely floating derelict, so low in the water that I might have missed her altogether except that a heave of her sluggish hull flashed a reflection of the suns new wan light from a polished deck-fitting into my eyes. I was so tired that I almost took no notice, assuming that the scrap of light had been mirrored from a discarded and floating beer can, but something made me pick up my binoculars and there she was; a dead creature which rolled under the blows of the short dawn chop.

I could see no one aboard the rolling hull. Her apparent abandonment, together with my weariness, tempted me to ease my helm to starboard and thus slip past the stricken boat that, like any other piece of floating junk, would have been out of sight within moments, and forgotten within hours, but curiosity and my sense of duty would not let me ignore her. There was still a slight chance that a wounded mariner was aboard, and so the wave-drenched wreck had to be boarded.

At least the weather was being kind. There was no steep chop or gusting wind to make boarding the waterlogged hull difficult. Instead the dawn was a calm, lovely finish to what had been a perfect tropical night during which I had been reaching northwards with every sail set; jib, staysail, foresail, mainsail and both jackyard topsails. Wavebreaker must have looked unutterably beautiful in that ghostly sunrise until the moment when I ran her head into wind and pressed the buttons which controlled the electric motors that furled her sails. I still found it odd to be sailing a boat on which everything was mechanised, electrified or computerised because by inclination and income I was a sailor of simpler tastes, but for the present I was Wavebreakers hired skipper, and Wavebreaker was a luxury charter schooner, and the kind of people who rented her expected to find her loaded down with as many gadgets as a space shuttle.

We had no charterers aboard on the morning I discovered Hirondelle. Instead we had been dead-heading, meaning that Wavebreaker sailed with only her crew aboard. The three of us had just spent four weeks off the western coast of Andros where Wavebreaker had been hired to make a television commercial for cat food. The notion of the commercial had been that an extremely wealthy cat had chartered the schooner to search the worlds oceans for the best-tasting fish, only to discover that Pussy-Cute Cat Food had already caught and canned the taste. The commercial must have cost Pussy-Cute millions of dollars, and Wavebreaker had been overrun with camera crews, designers, visualisers, scriptwriters, cat-handlers, fish-handlers, directors, account executives, make-up girls, hairdressers, line-producers, assistant-producers, real producers, as well as all the girlfriends and boyfriends and hermaphrodite-friends of everyone involved. Serious adults had argued passionately about the motivation of the rich cat, and even I, who had thought myself immune to the insanities of the film world, had been astonished when an elderly actor had been specially flown down from New York to imitate the beasts miaow because the real thing had not been considered sufficiently authentic. The elderly actor, coming aboard Wavebreaker for the first time, had stared at me in astonishment; then, though he had never seen me in his life before, he spread his arms in familiar and lavish welcome. Sweet Tom! He had called me by my fathers name, and I had smiled wanly, then confessed that I was indeed Tom Breakspears son. How could you not be? the New York actor had demanded. Youre the very image of him! Will you remember me to the old rascal? Everyone knew my father. Everyone wanted me to know how they just loved my father. Everyone told me just how like my father I looked, though very few dared ask me from which of my fathers wives I had been whelped.

But now, thank God, I was free of miaowing Thespians, and Wavebreaker was sailing back to her home port on Grand Bahama where, in just twenty-four hours time, she would begin her last charter of the season. Then came Hirondelle to spoil the dawn.

I had been alone on deck when I first saw the wreck. Ellen had been sleeping in the stern-cabins king-sized bed, and Thessy had been snoring in one of the clients forward cabins. It was only when we were dead-heading that we were allowed to make free with the air-conditioned luxuries of the boats staterooms. The brochure promised our charterers the authentic sea-salt taste of tropical seafaring, though sailing on Wavebreaker was about as authentic as Pussy-Cutes miaow.

The whine of the sail-furling motors brought an alarmed Thessy running on deck. He stood blinking in the new daylight, then stared in astonishment at the waterlogged white hull which rolled sluggishly under our lee. We were now close enough to read the name on her transom and could see that the derelict was called Hirondelle, and hailed from Ostend. The small waves slopped and splashed across the neat blue lettering. It seemed a terrible waste to have run from that grim North Sea port safely across the Atlantic to what must have seemed like the sunlit paradise of the Bahamas sheltered shallow waters, only to meet this savage fate.

And something savage had happened to Hirondelle: She was a mastless mess, trailing a tangle of sodden rigging. Her coachroof and deck were riddled with holes; so many holes that groups of them had joined together to make dark, jagged and splintered craters. My first thought was that someone had run berserk with an industrial drill, but then I saw a glint of brass in her scuppers and I recognised an empty cartridge case and knew I was looking at bullet holes. Hirondelle had been machine-gunned. Someone had poured fire at her, but she had stayed afloat because she was one of the few production boats that were built to be unsinkable. Foam had been sandwiched between her fibreglass layers and crammed into every unused space inside her hull and that foam was now holding her afloat, fighting against the dead weight of her ballast and engine and winches and galley stove.