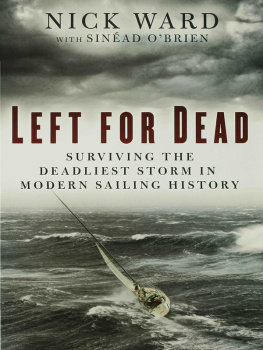

LEFT FOR DEAD

FOR CHRIS

LEFT

FOR

DEAD

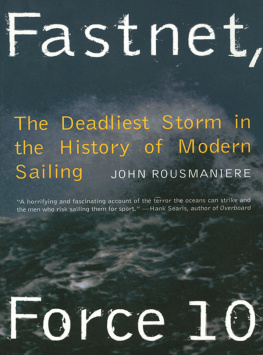

Surviving the Deadliest Storm

in Modern Sailing History

NICK WARD

with Sinad O'Brien

BLOOMSBURY

Copyright 2007 by Nick Ward and Sinad O'Brien

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Bloomsbury USA are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA HAS BEEN APPLIED FOR.

eISBN: 978-1-59691-930-3

First U.S. Edition 2007

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

CONTENTS

It is over 26 years since I sat alone

at a bedside table with paper and pen supplied to me by Treliske Hospital in north Cornwall. Then I thought it important to record the facts, as I knew them, while they were still vivid in my mind. I was tired and overcome, but the words wrote themselves. The date was 15 August 1979 the day after the most shattering event of my life. This last quarter-century has given me plenty of time to reflect on the longest 14 hours of my life, which I shared with my friend and crewmate Gerry Winks aboard the yacht Grimalkin.

Four days before, on 11 August 1979,1 had set sail on my first ever Fastnet Race, part of a crew of six men: David Sheahan (owner and skipper of Grimalkin), his son Matthew Sheahan, Gerald Winks, Mike Doyle and Dave Wheeler. All of us on Grimalkin were excited and proud to be taking part in this 600-mile offshore classic. The race began in near-perfect conditions, but on day three the unforeseen happened Grimalkin, along with many of the other yachts, got caught up in the deadliest storm in the history of modern sailing.

The Fastnet Race disaster of 1979 claimed the lives of 15 yachtsmen, including two of Grimalkin's crew, David Sheahan and Gerald Winks. What happened during Fastnet '79 has been much written about, including a great deal of intrigue about the circumstances in which Gerald Winks and I were left for dead, abandoned by our shipmates, at the height of the storm. I have seen little or nothing of the other three surviving members of Grimalkin's crew, Mike Doyle, Dave Wheeler and Matthew Sheahan, over the last quarter-century. The few days we spent together aboard Grimalkin have been written about, discussed and debated in the yachting press, on television and by the media. But we, the remaining crew, the survivors, the four of us, have not spoken collectively, either in public or privately. I have always felt there has been some bad feeling, some uneasiness between us. Recently, during a television documentary, I heard Matthew say that he had felt 'closure'. Like me, I am sure that he too, along with Mike and Dave, has his own perception of the events that took place on that god-awful August day.

In the months following the disaster I gave several interviews. I know now that I never portrayed my true feelings nor gave the full story. I was a 24-year-old man in deep shock and in no position to evaluate my situation objectively. Much of what I read about the circumstances surrounding my story caused me such pain that I simply wanted to block it all out. In 1980 I took the decision not to be interviewed again on the subject. Since then, every time a television company, a film company or a journalist has knocked on my door asking for an interview, I have declined.

That was until September 2004, when I was approached by a documentary filmmaker called Sinad O'Brien. She had by chance heard a story of how a young man had been abandoned with his crewmate in the Irish Sea. Of course, my first reaction to this approach was one of unwillingness. Now, though, I had begun to write for myself, not specifically about the Fastnet Race, but personal thoughts in the form of a journal. I discussed this new approach at length with my wife Chris, and then I agreed to meet Sinad. She was interested in pursuing the story for a documentary or feature film, and had come across a video clip in which I was pictured with my dead crewmate Gerald Winks at my feet. The footage was taken moments before a Royal Navy Sea King helicopter rescue. Watching the streaming video on my computer screen brought back immediately, all too vividly, a slice of time buried but not forgotten. I was shocked, overcome and glad that Chris was with me. Over the next few months, Sinad, this bright, young, vibrant, tenacious Irish woman, was to tease out memories from me, some long covered up, almost denied. In front of this stranger I began to purge myself of 25 years of pent-up emotions.

After much indecision I decided to concentrate my latent emotions into a book to finally put down on paper the feelings of anger, torment, helplessness, despair and pure bloody-minded frustration I had felt while trying to survive the near impossible.

Sinad was able to explain to me the best way to embark upon the project. It was not long before we became partners in this book. My co-writer's input from the very start has been inspirational. I recognised her talent and enthusiasm immediately. Once she realised I had a story to tell, Sinad brought her incisive style and her structuring skills to the writing of this book. She showed me how to add without veering off the line the line of being true to myself. Without Sinad this story would have been left as a private journal, unpublished.

This book is as much for Gerald Winks as it is for me for if it were not for him, I would not be here to tell this story. This is the, until now, untold story of what became of Gerry and me on that day, 14 August 1979. This is my 'closure'.

NICK WARD, 2007

I was born in the little south-coast

village of Hamble, in Hampshire. I was the youngest of four children, three boys and one girl, and my upbringing was pretty much the usual for a small village by the sea. Hamble is no ordinary village, though; life in the village is inextricably bound to fishing, sailing and, in particular, yacht racing. Some of the finest national and Olympic sailing champions were born here, sailed here or are connected in some way with this place. If you are born in Hamble, it is inevitable that the sea or sailing will play some part in your growing up.

And certainly my father, Pa, instilled in his three sons from a very young age a love of the water and all things nautical, particularly sailing. My first sailing lessons were at the age of four in a pram dinghy Pa built for me during the winter of 1959/60. In the garage of our home, I would sit in a wooden rocking chair watching Pa plan and shape the plywood dinghy. The love, care and attention he put into building it were extraordinary. Perhaps because I was the youngest and he was that much older when I was growing up, Pa had the time to do things for me he had not had for the others. I know I spent far more time with him than my siblings had, and although I adored both my parents, Pa and I had a particular, wonderful affinity. Many nights I fell asleep in the rocking chair to the sound of him sawing, planing and nailing, then to be carried to bed in his arms. He was well built, six foot two, and for as long as I knew him had white hair, and an untipped Senior Service cigarette in his hand. Articulate and well read, he captivated me with bedtime stories and tales of the sea. He read me many tales, classic accounts of ships and their crews sailing the southern oceans and rounding Cape Horn. I wanted to be there, with the characters in the books. I can remember the absolute thrill I felt when we launched the dinghy down at Hamble quay the following spring and also the crowd that it drew. Pa had named her

Next page

![Nick Cracknell - The Quiet Apocalypse [= Island Zero]](/uploads/posts/book/837188/thumbs/nick-cracknell-the-quiet-apocalypse-island.jpg)