1948

She had left his desk exactly as it was. As had been true for weeks, she spent the afternoon seated in his easy chair, smelling himthe old books overflowing from their cases, the hint of cigar smoke that always hung about him in life, a smell that brought him back to her like a spirit upon the air.

She could not bear to move his things, as if rearranging his office or going through his papers would break the spell, as if then he would truly vanish from this place he loved more than any other.

Her daughter leaned against the windowsill, the morning sun on her back. Behind her, beyond the sloping lawn, beneath the branches of the willows, a mallard and her ducklings paddled in a line across the pond. Nearer to the house, the tulips and irises had returned, pushing up through the grass, adding patches of yellow and purple to the green. Her great-grandchildren chased each other around the flowers, their shouts faint but audible through the glass.

Her daughter repeated herself.

Are you well enough to give the eulogy, Mother?

She did not answer. As her daughter looked at her, she seemed, for the first time, to look her age of ninety-two years.

I can help you write it.

Her mother continued staring out the window. He loved this time of year, Elizabeth.

I know.

We planted those bulbs together. It took us hours. I did not think they would outlast him. He would be smiling at their color now. He stood where you are standing when he could not decide what to write, when the words refused to come.

The funeral is in three days, Mother. If you are going to speak, we need to get to work.

Is the Prime Minister coming?

Elizabeths eyes shifted, as if she did not want to answer. He declined.

He has always been a coward.

He is a politician, Mother. They do what is popular.

You are old enough to remember when Prime Ministers did their duty, Elizabeth. What did the Queen say?

The Palace has not yet responded. Some say if she does come, there will be an uproar.

Are they still trying to tear down his statues?

Some are.

Have they succeeded?

Not yet.

The older woman nodded, closing her eyes.

Should I just write it for you, Mother?

No. You are not ready.

Not ready?

There are things you do not know.

What things?

He would have told you, said the mother, still avoiding her daughters eyes, He wanted to. More than once he asked me if he could share parts of it with you, leaving out the parts I wished to keep secret. It was his love for me that stopped him.

What are you talking about? asked the daughter, growing impatient.

I told him that we must share all of the story or none of it. But I was never ready to share all of it, even with you, and even in the end, when he asked me once more.

What story?

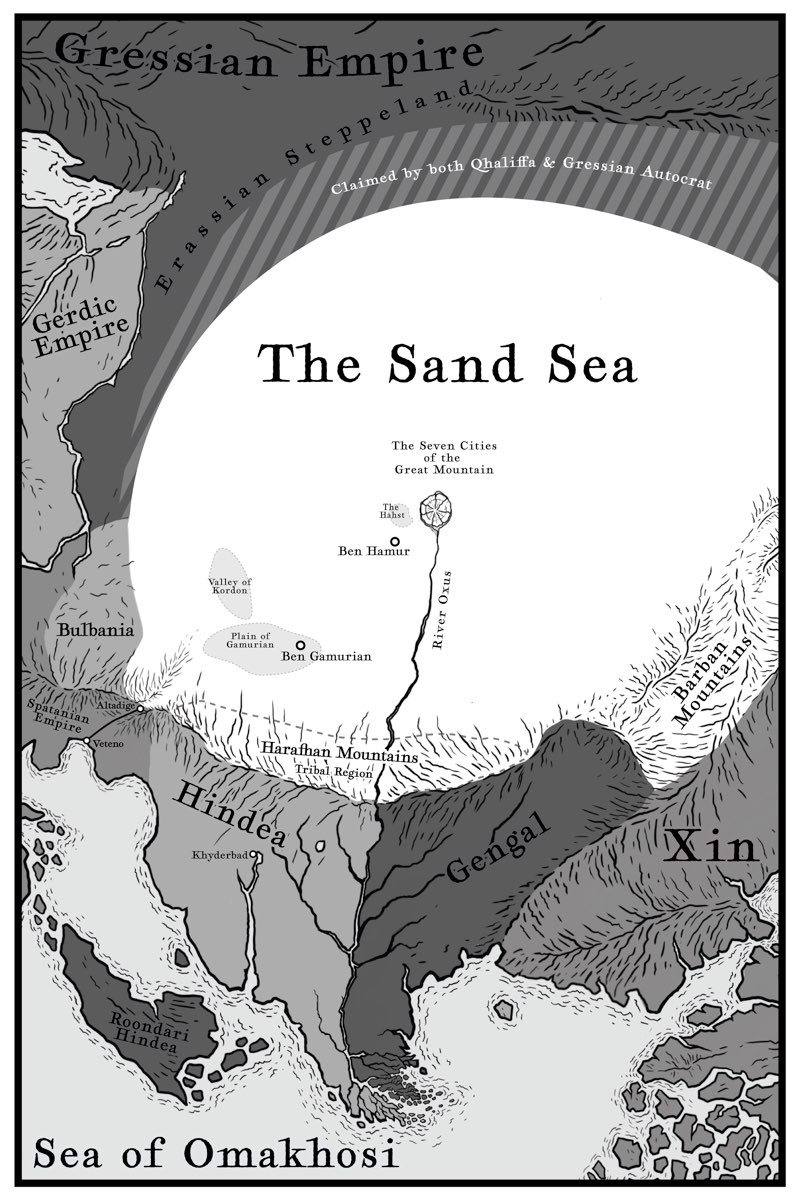

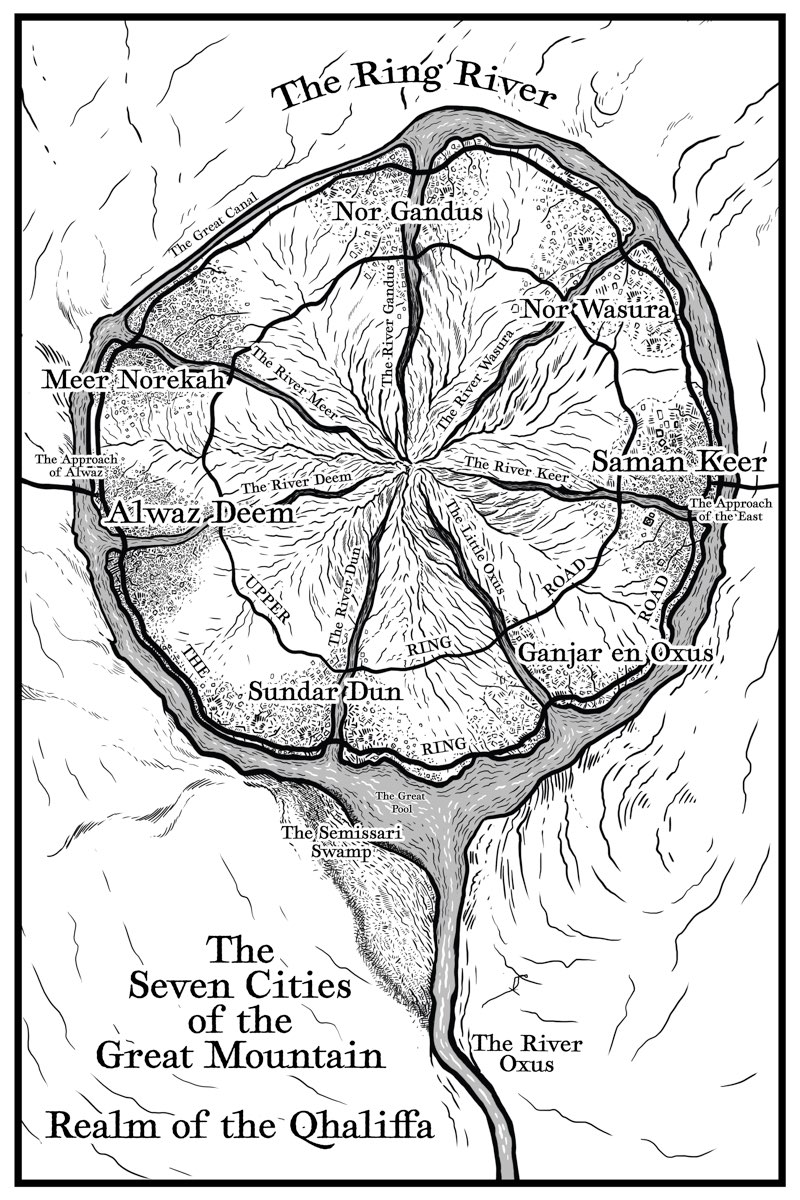

He could always see, Elizabeth. The past, the present, that which was yet to come. He gained that vision in the desert, and it never fully left him. He saw all of this long ago. He knew they would try to diminish him, to erase his place in our history. To his credit, he did not let that change him.

Mother, you are not making sense.

Your father became as famous as a man can become, Elizabeth. Even those who do not care to know much of anything can still state the basic facts of his life. But those are not the things I am talking about. There are things we hid from the press, from his biographers, and from you and your sisters.

Elizabeth stared as if a stranger had suddenly replaced her mother. Her eyebrows furrowed, and the lines deepened across her forehead. Elizabeth was still beautiful in her late middle years, with the strong jawline of the woman in front of her, but the eyes and the auburn hair of her father.

What are you trying to say? That I dont know my own father well enough to write his eulogy? I am a grandmother myself, Mother, not a child

The older woman smiled. Yes, but you are still my child, Elizabeth, and always will be. Open that drawer. The deep one on the bottom left-hand side of the desk.

Elizabeth walked to the desk, her cheeks flushed with frustration.

She pulled the drawer handle. It opened reluctantly, heavy with the contents inside. She lifted out an old dirty helmet made of pith and smelling of stale sweat and other things she could not identify.

She set it on the desk. This?

No, underneath that. But when I am gone, you must protect that and treat it with reverence. That was his helmet.