The Forgotten Children

1788

The Gold Rush

The Great Race

Published by Little, Brown

ISBN: 978-1-4087-0574-2

Copyright 2012 by David Hill

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Maps on pp.viii-xvi Ice Cold Publishing

Cover: map detail South Australian Museum.

Chart of Duffs Track in the Pacific Ocean, 1797

A Missionary Voyage to the Southern Pacific Ocean performed in the years 1796, 1797 and 1798 in the Ship Duff , London, 1799.

Ships from the painting HMS Investigator and LGeographe by Ian Hansen from the collection of the Australian National Maritime Museum and reproduced with kind permission of Ian Hansen.

Cover design by Christabella Designs

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Little, Brown

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DY

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

C ONTENTS

To Stergitsa

Wherever possible I have avoided the word discover in relation to European forays around and into Australia and other parts of the New World, but in some instances it was unwieldy to avoid the verb. Where I have used discovered in relation to European exploration, I do so meaning the first European discovery. I hope readers are comfortable with this it does not indicate that I believe Australia or any other lands were undiscovered before Europeans landed on or settled them.

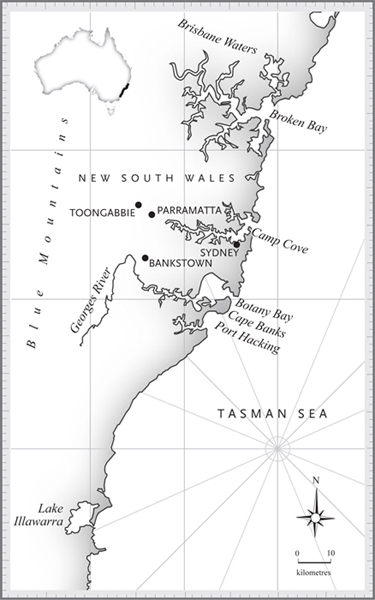

Sydney and its environs

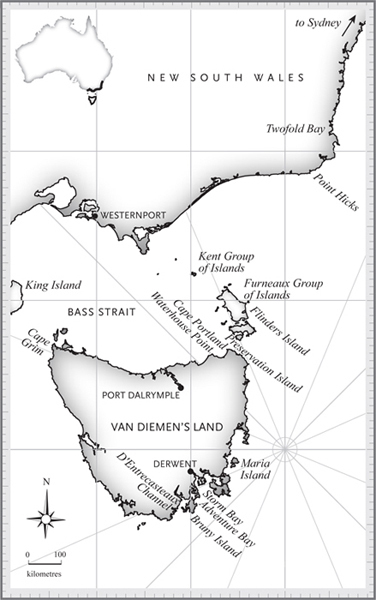

Van Diemens Land

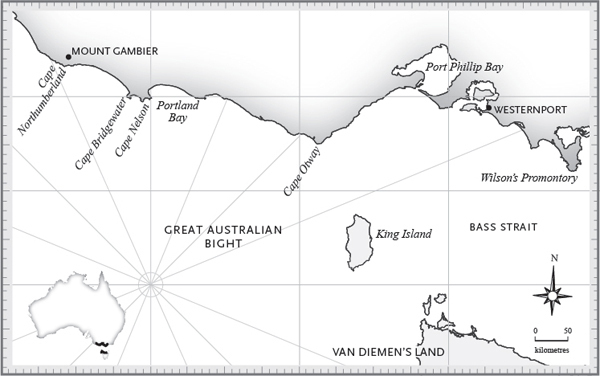

South-eastern coast

South Australian gulfs

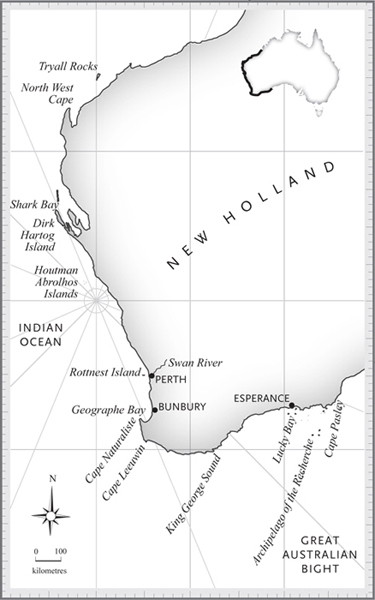

West coast to North West Cape

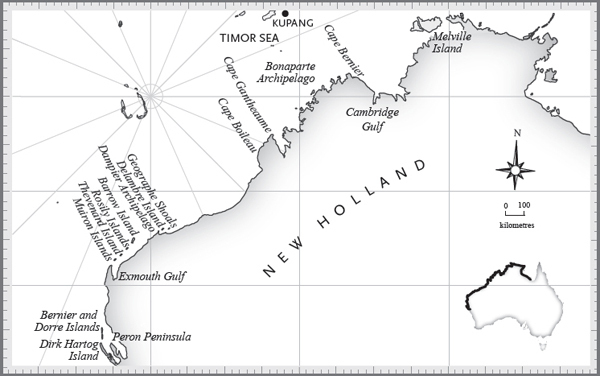

North West Cape

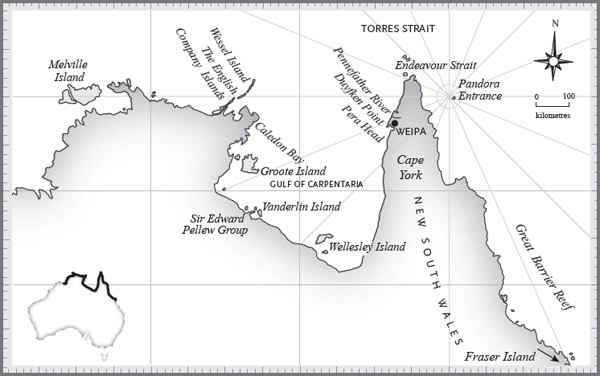

Gulf of Carpentaria to Fraser Island

O n the afternoon of 8 April 1802, in a remote part of the Southern Ocean where no ship had ever sailed before, two explorers had a chance encounter. Sailing west along the worlds largest remaining stretch of uncharted coast was the French ship Le G ographe , captained by Nicolas Thomas Baudin; heading east was the English ship Investigator , captained by Matthew Flinders.

Baudin and Flinders were both on the same quest. They had each been sent by their government to explore thousands of kilometres of unknown coast of the Great South Land, and to find out if the west coast of New Holland, as it was called then, and the east coast of New South Wales, 4000 kilometres away, were part of the same land or separated by a sea, or a strait. Over the next three years, Baudin and Flinders would both command ill-fated expeditions as they rivalled each other to produce the first complete map of this largely unexplored continent.

*

The French and the British were both relative latecomers to the Great South Land. For more than 200 years, other European navigators and explorers had visited, and some had charted, various parts of its coast.

The first documented European visits to Australia were both in 1606: one by a Spanish explorer, Luis Vez de Torres; and one by a Dutchman, Willem Janszoon. But there is some pretty compelling evidence suggesting that other Europeans had arrived much earlier, including surviving maps indicating Portuguese seafarers may have sailed along large sections of the Australian coast in the early 1500s.

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to sail into the Indian Ocean, when Bartholomeu Diaz navigated the Cape of Good Hope in 1486 and, a little more than a decade later, in 1497, Vasco da Gama sailed two ships to India and then back to Lisbon. Over the next century, the Portuguese developed a network of trading routes in the southern hemisphere, connecting South America, southern Africa, India and the Pacific as far as Timor. A major impetus for the trade was to collect spices and herbs that were not then available in Europe, including ginger, cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, lemongrass, curry, vanilla and fennel.

The theory that the Portuguese may also have reached as far as Australia is largely based on old maps that contain a number of coastal features strikingly similar to the Australian shoreline. The beautifully made French Dieppe maps are believed to be reproductions of Portuguese originals, and they show a land mass named Java la Grande between Indonesia and Antarctica. They were made by the Dieppe Cartography Department for wealthy and royal patrons and included the Dauphin map of 1547, which was ordered by King Francis I of France as a gift to his son the Dauphin, who later became King Henry II. The map, which is now in the British Library, depicts a coastline that appears similar to the features of the Australian coast from Cape York to the current-day southern Victoria.

Other surviving charts from this period include a book of maps dated 1542 that was presented to Englands King Henry VIII by Frenchman Jean Rotz, an artist-cartographer who was a member of the Dieppe School. The Jean Rotz maps depict a coastline similar to some of Australias north and east coasts. Then in 1566 Nicolas Desliens created a world map whose depiction of Australia had similar features to one of the far north-east coast of the continent made 200 years later by Captain James Cook. Also supporting the theory of an earlier Portuguese discovery of Australia was the claim in 1836 by two whalers that they had found the remains of a sixteenth-century Portuguese ship on a deserted stretch of beach on the southern Australian coast near Warrnambool. There were other reported sightings over the next few decades, but no more evidence has been found since the 1880s, despite the offer of a $250,000 reward by the Victorian state government in the late 1970s.

Historians are divided as to whether the maps are proof that the Portuguese had, albeit unwittingly and presumably unknowingly, discovered Australia in the early sixteenth century. Some argue the coastal features on the maps are too accurate for their likeness to the Australian coast to be a coincidence. The explorer Matthew Flinders was among those who thought the Portuguese had been to the Great South Land many years before him; he said of the surviving maps that the direction given to some parts of the coast, approaches too near the truth, for the whole to have been marked by conjecture alone.

Others, however, argue the maps are merely theoretical constructs and not the result of actual discovery. It has also been argued that the features of Java la Grande on the Dieppe maps could resemble the coast of Indonesia and Indochina as much as they do Australia.