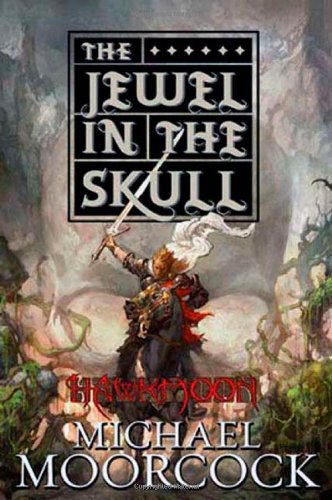

Chapter Two - YISSELDA AND BOWGENTLE

COUNT BRASS had led armies in almost every famous battle of his day; he had been the power behind the thrones of half the rulers of Europe, a maker and a destroyer of kings and princes. He was a master of intrigue, a man whose advice was sought in any affair involving political struggle. He had been, in truth, a mercenary; but he had been a mercenary with an ideal, and the ideal had been to set the continent of Europe toward unification and peace. Thus he had, from preference, leagued himself with any force he judged capable of making some contribution to this cause. Many a time he had refused the offer to rule an empire, knowing that this was an age when a man could make an empire in five years and lose it in six months, for history was still in a state of flux and would not settle in the Count's lifetime. He sought only to guide history a little in the course he thought best.

Tiring of wars, of intrigue, and even to some extent, of ideals, the old hero had eventually accepted the offer of the people of the Kamarg to become their Lord Guardian.

That ancient land of marshes and lagoons lay close to the coast of the Mediterranean. It had once been part of the nation called France, but France was now two dozen duke-doms with as many grandiose names. The Kamarg, with its wide, faded skies of orange, yellow, red, and purple, its relics of the dim past, its barely changing customs and rituals, had appealed to the old Count and he had set himself the task of making his adopted land secure.

In his travels in all the Courts of Europe he had discovered many secrets, and thus the great, gloomy towers that ringed the borders of the Kamarg now protected the territory with more potent, less-recognizable weaponry than broadswords or flame-lances.

On the southern borders, the marshes gradually gave way to sea, and sometimes ships stopped at the little ports, though travelers rarely disembarked. This was because of the Kamarg's terrain. The wild landscapes were treacherous to those not familiar with them, and the marsh roads were hard to find; also, mountain ranges flanked its three sides on land. The man wishing to head inland disembarked farther east and took a boat up the Rhone. So the Kamarg received little news from the outside world, and what it did receive was usually stale.

This was one of the reasons why Count Brass had settled there. He enjoyed the sense of isolation; he had been too long involved with worldly affairs for even the most sensational news to interest him much. In his youth he had commanded armies in the wars that constantly raged across Europe. Now, however, he was tired of all conflict and refused all requests for aid or advice that reached him, no matter what inducement was offered.

In the west lay the island empire of Granbretan, the only nation with any real political stability, with her half-insane science and her ambitions of conquest. Having built the tall, curved bridge of silver that spanned thirty miles of sea, the empire was bent on increasing her territories by means of her black wisdom and her war machines like the brazen ornithopters that had a range of more than a hundred miles. But even the encroachment of the Dark Empire into the mainland of Europe did not greatly disturb Count Brass; it was a law of history, he believed, that such things must happen, and he saw the ultimate benefits that could result from a force, no matter how cruel, capable of uniting all the warring states into one nation

Count Brass's philosophy was the philosophy of experience, the philosophy of a man of the world rather than a scholar, and he saw no reason to doubt it, while the Kamarg, his sole responsibility, was strong enough to resist even the full might of Granbretan,

Having nothing, himself, to fear from Granbretan, he watched with a certain remote admiration the cruel and effi-cient manner in which the nation spread her shadow farther and farther across Europe with every year that passed.

Across Scandia and all the nations of the north the shadow fell, along a line marked by famous cities: Parye, Munchein, Wien, Krahkov, Kerninsburg (itself a foothold in the mysterious land of Muskovia). A great semi-circle of power in the main continental land mass; a semi-circle that grew wider almost every day and must soon touch the northernmost princedoms of Italia, Magyaria, and Slavia. Soon, Count Brass guessed, the Dark Empire's power would stretch from the Norwegian Sea to the Mediterranean, and only the Kamarg would not be under its sway. It was partly with this knowledge in mind that he had accepted the Lord Guardianship of the territory when its previous Guardian, a corrupt and spurious sorcerer from the land of the Bulgars, had been torn to pieces by the native guardians whom he had commanded.

Count Brass had made the Kamarg secure from attack from outside and from menace from within. There were few baragoons left to terrorize the people of the many small villages, and other terrors had been dealt with also.

Now the Count dwelt in his warm castle at Aigues-Mortes, enjoying the simple, rural pleasures of the land, while the people were, for the first time in many years, free from anxiety.

The castle, known as Castle Brass, had been built some centuries before on what had then been an artificial pyramid rising high above the center of the town. But now the pyramid was hidden by earth in which had been planted grass and gardens for flowers, vines, and vegetables in a series of terraces. Here there were well-kept lawns on which the children of the castle could play or adults stroll, there were the grape-vines that gave the best wine in the Kamarg, and farther down grew rows of harricots and patches of potatoes, cauliflowers, carrots, lettuce, and many other common vegetables, as well as more exotic ones like the giant pumpkin-tomatoes, celery trees, and sweet ambrogines. There were also fruit trees and bushes that supplied the castle through most of the seasons.

The castle was built of the same white stone as the houses of the town. It had windows of thick glass (much of it painted fancifully) and ornate towers and battlements of delicate workmanship. From its highest turrets it was possible to see most of the territory it protected, and it was so designed that when the mistral came an arrangement of vents, pulleys, and little doors could be operated and the castle would sing so that its music, like that of an organ, could be heard for miles on the wind.

The castle looked down on the red roofs of the town and at the bullring beyond, which had originally been built, it was said, many thousands of years ago by the Romanians.

Count Brass rode his weary horse up the winding road to the castle and hallooed to the guards to open the gate. The rain was easing off, but the night was cold and the Count was eager to reach his fireside. He rode through the great iron gates and into the courtyard, where a groom took his horse.

Then he plodded up the steps, through the doors of the castle, down a short passage, and into the main hall.

There, a huge fire roared in the grate, and beside it, in deep, padded armchairs, sat his daughter, Yisselda, and his old friend Bowgentle. They rose as he entered, and Yisselda stood on tiptoe to kiss his cheek, while Bowgentle stood by smiling.

"You look as if you could do with some hot food and a change into something warmer than armor," said Bowgentle, tugging at a bellrope. "I'll see to it."

Count Brass nodded gratefully and went to stand by the fire tugging off his helmet and placing it with a clank on the mantel. Yisselda was already kneeling at his feet, tugging at the straps of his greaves. She was a beautiful girl of nineteen, with soft rose-gold skin and fair hair that was not quite blonde and not quite auburn but of a color lovelier than both. She was dressed in a flowing gown of flame-orange that made her resemble a fire sprite as she moved with graceful swiftness to carry the greaves to the servant who now stood by with a change of clothes for her father.