Battleship

Introduction

Many authorities in 1945 believed that the era of the man owar, as we have known her for 500 years, ceased with the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan. More than 30 years later, the deep concern with the rise of Russian naval power, from a poorly regarded and diminutive force, to the ever-growing strength it flaunts today, proves that the importance of the fighting ship is at least as great as it has ever been. Men owar are being built, counted, assessed and exercised, their bases modernized and created, tactical and strategic considerations debated, with the same vigour today as at the beginning of the century and during the Napoleonic wars.

As I write, a war is being fought in Africa which may decide whether or not the Russian Empire will control the sea routes from the Middle East oilfields. Gunboat diplomacy is still with us; doubtless always will be. Today the theoretical debate of aircraft carrier versus nuclear submarine is as powerfully argued as battleship versus submarine from, say, 1910 until 1940. As far as the man owar is concerned, never has the old aphorism Plus a change, plus cest la mme chose applied more truly.

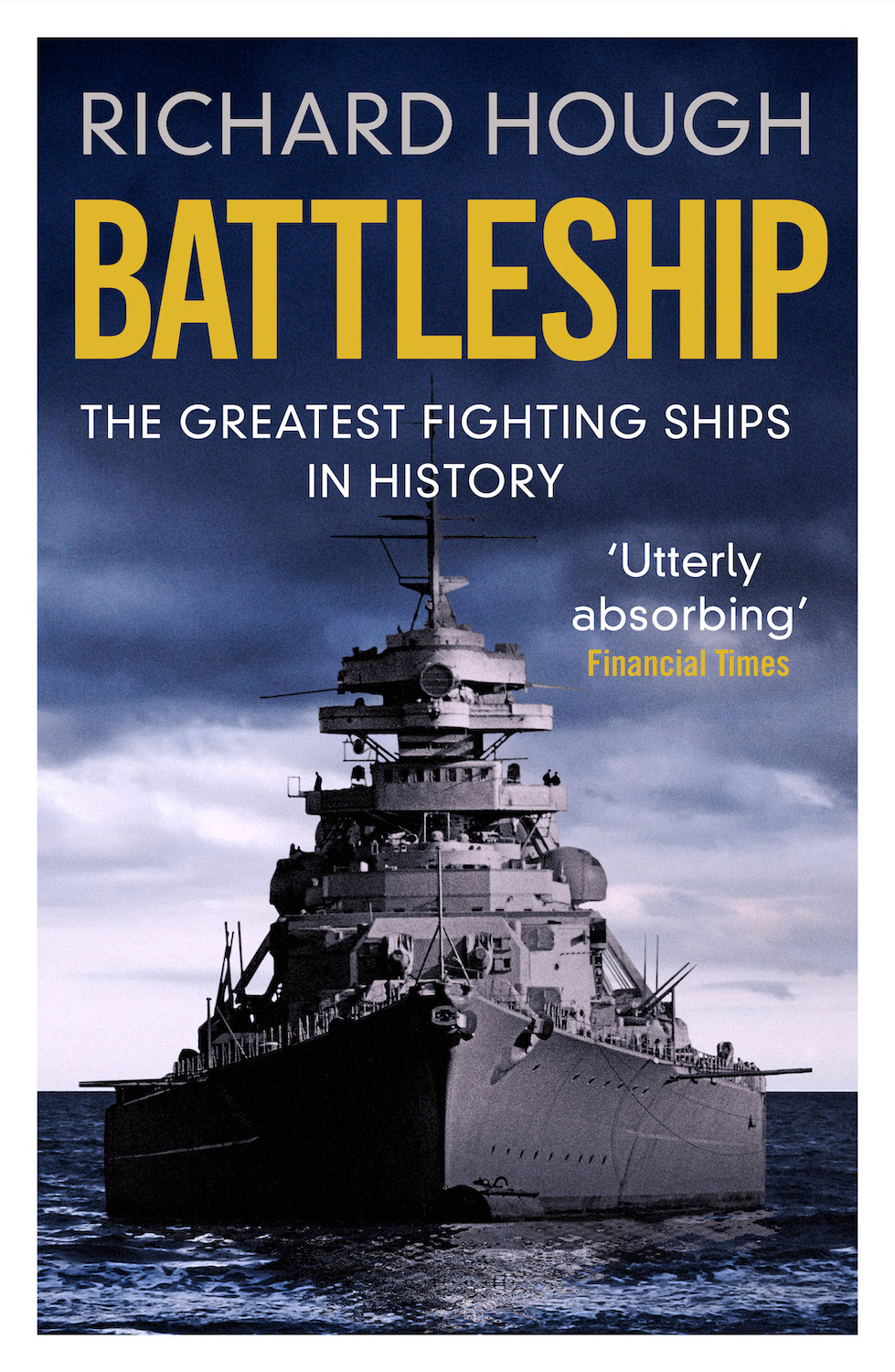

In this book, however, I am not concerned with the present-day fighting ship. I leave it to future historians to write of 40,000-ton amphibious assault ships, radar picket assault ships and cruiser helicopter carriers; pausing only to comment that we are in the throes of another hideous era of naval architecture. What I have attempted to provide in this book is an abbreviated history of the man owar and her battles over 400 years by singling out chronologically examples that I consider significant and interesting, stitching them into a pattern of progress from galleon to super-Dreadnought.

In the last chapter I mention my love affair with the battleship. It began when I was a boy, and its ardour was inflamed by the Coronation Naval Review of 1937, the last occasion when the big gun platform the battleship was everywhere recognized as the prime weapon and arbiter in sea warfare. The marriage was consummated when I watched battleships from above going about their affairs majestically and purposefully during the 193945 war. Our golden wedding, so to speak, was celebrated when I took a small part in the reactivation of the mighty USS New Jersey in 1967, whose subsequent successful if brief career seemed to prove that the battleship was not dead after all.

I have known naval officers who have commanded diminutive motor torpedo boats, cruisers, carriers, squadrons and fleets. Whatever their varying qualities may have been, affection for their men owar has always been a common characteristic. Lord Howard of Effinghams words of admiration for his Ark Royal formed themselves into an Elizabethan love ode: I think her the odd ship in the world for all conditions, and truly I think there can be no great ship make me change and go out of her. Then he made sail and thrashed the Spanish Armada to prove that love and the will to win are indivisible, too.

The careers of several of the ships I have singled out were as brief as they were glorious. Both the Bismarck of 1941 and the Bonhomme Richard of 1799 succumbed after defeating their adversary in their first fight on their first operational voyage. By contrast, the Dutch Zeven Provincien, for example, saw de Ruyter through all his greatest battles. The Warspite fought through two wars, the New Jersey in three. The Kellys, career was crowded into hectic months, the Victory is still a flagship after 200 years.

Richard Hough

March 1978

Acknowledgements

I am especially grateful to Admiral of the Fleet the Earl Mountbatten of Burma kg, pc, gcb, om, etc., to the late Oliver Warner, and to Tom Pocock, for their own special contributions to this book.

R. H.

Ark Royal

Galleon, 1587, England

Accounting for the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 Sir Walter Raleigh wrote:

The Spaniard had an army aboard them, and [the English C.-in-C.] had none: they had more ships than he had of higher building and charging; so that, had he entangled himself with those great and powerful vessels, he had greatly endangered this Kingdome of England

Raleigh himself was out of favour with Queen Elizabeth I and had a shore appointment at the time of the Enterprize of England, as the Spaniards called their Armada operations, but his ship, the Ark Royal, took a leading part in the fighting and was the flagship of Lord Howard of Effingham. In her design and construction, and in her career, there can be seen all that made English fighting ships and fighting tactics the best in the world in the sixteenth century.

For 100 years and more before the Spanish attack on England the Portuguese and Spaniards had led the world in exploration and had dominated distant maritime trading. Navigators of peerless courage had touched and charted much of the coastline of the Americas, created an empire in Central and South America, set up trading stations in Africa and India, doubled the Cape of Good Hope as well as the Horn, grown rich on the spices of the East as well as the gold of Peru.

By the Bull of Demarcation of 1493 the world no less had been divided into two between these Iberian powers: everyone else would, from then on, be trespassing. For these staggering accomplishments the Portuguese and Spanish sailors and traders relied largely upon caravels and carracks of the most basic design and with an overall length of no more than 100 feet.

But, as the Americans discovered 250 years later, you cannot create a merchant fleet without providing for its protection. From this need originated the Spanish and Portuguese fighting galleons, originally no more than caravels with a couple of built-up wooden castles for soldiers a fore and an after castle. Enemy ships were not destroyed. They were captured by boarding at the waist between the castles, while the defenders hurled missiles upon them from the castles or descended to fight hand to hand with the boarders.

Defensive and offensive methods were elaborated, nets were laid in the waist to entrap the boarders, like barbed wire in the First World War. Guns were set up in the castles, and light railing pieces of doubtful reliability, but of undoubted morale-damaging usefulness, were added. Then some unknown soldier seized upon the idea of placing larger cannon in the waist itself, one or two to each side to strike at the enemy before he could board. A good solid plank was disposed above the guns to protect the crews, and acquired the name gunwale. The answer to this was a second tier of guns in the waist disposed one above the other and decked over. Decks were similarly added to the castles. In this way, spasmodically over the years, there emerged the decked fighting ship with tiers of guns disposed within gun ports: the stately Spanish galleon.

Henceforward the gun would be the primary weapon of sea warfare until the arrival of the super-torpedo and the bomb of the Second World War, and then the missile. But the Spanish and Portuguese, who dominated the high seas, still regarded sea fighting as an extension of land warfare and fought accordingly soldier against soldier, the target the enemys castles, or ship, as if the sea were no more than an inconvenient moat. Guns were for destroying the enemys rigging, and thus his mobility.