This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1945 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

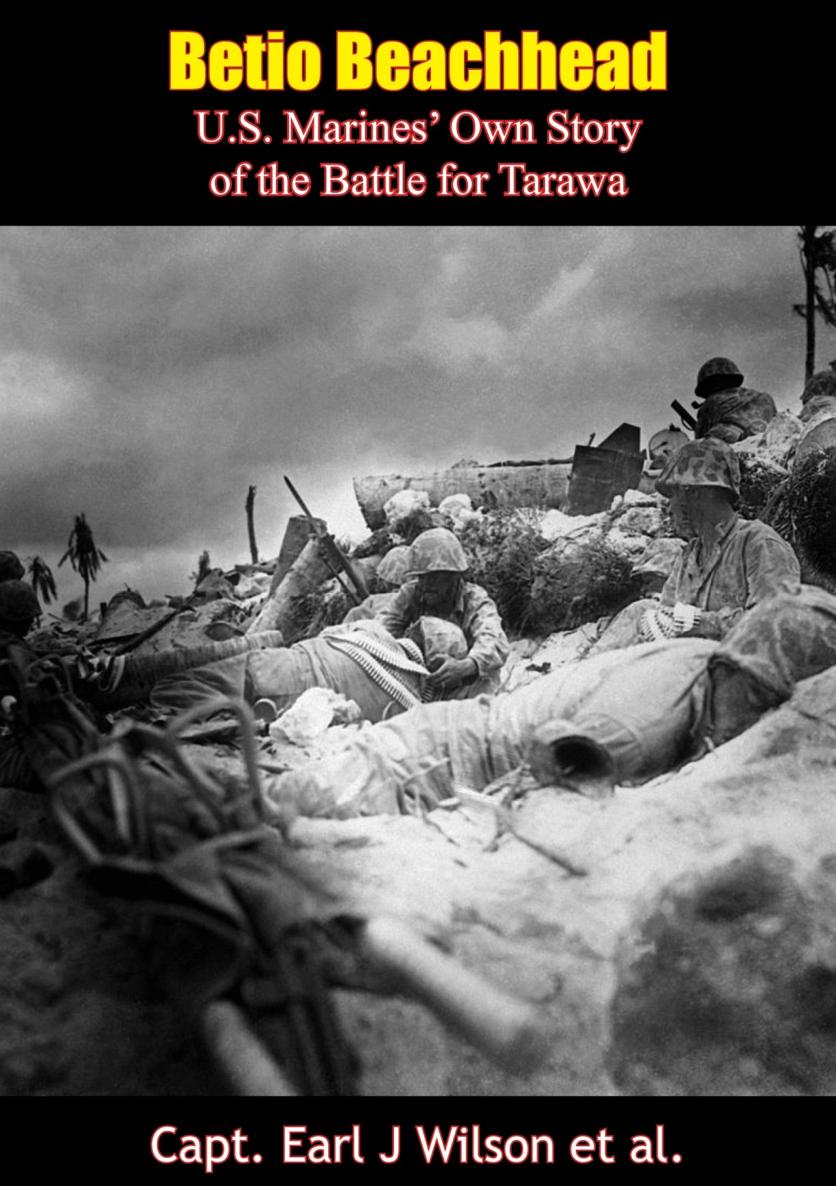

BETIO BEACHHEAD:

U.S. Marines Own Story of The Battle for Tarawa

An account documented and written by

four Marines who went through the battle.

THEY WERE:

Captain Earl J. Wilson and

Marine Combat Correspondents

Master Technical Sergeants

Jim G. Lucas (now 2 nd Lt.) and Samuel Shaffer, and

Staff Sergeant C. Peter Zurlinden (now 2 nd Lt.)

INTRODUCTION

Public interest in amphibious warfare has greatly increased during the course of this war. Perhaps the most classical example of a strictly amphibious operation was the taking of Tarawa. In order that a popular presentation of that action might be made to the American public, as one of my last acts as Commandant of the Marine Corps, I arranged for Marine personnel who participated to return home to prepare this account.

Tarawa, from the public viewpoint, will long stand as one of the most spectacular battles Marines have ever fought. To the public and to the Corps alike, it will endure as a monument of unsurpassed heroism, built by every man who was there.

Its importance to the Marine Corps as a tactical experience in amphibious warfare transcends that of any operation in this highly specialized field to date. The hard-bought lessons of Tarawa are serving all Allied forces in the resolute prosecution of our amphibious offensives, and will thereby speed our victory over the enemy in the Pacific.

T. Holcomb

General, United States Marine Corps

1

Last week some two to three thousand U.S. Marines, most of them now dead or wounded, gave the nation a name to stand beside those of Concord Bridge, the Bonhomme Richard , the Alamo, Little Big Horn and Belleau Wood. The name was Tarawa.

Time Magazine, December 6, 1943.

For two dragging weeks the crowded transports had been zigzagging their way through the blue waters of the South Pacific and for the Marines aboard it had been two long weeks of weary monotony.

They were headed for one of the bloodiest battles in Marine Corps history, but they did not know that then. They did not even know where they were going.

At the end of these two weeks, on November 14, 1943, they found out. A message from the Task Force Commander wigwagged from ship to ship, Give all hands general picture of projected operations....

It was then that Marines of the Second Division heard for the first time the name of the tiny coral atoll in the Central Pacific where they were to make history.

Tarawathe Marines rolled the strange name off their tongues and repeated it to each other. Now they knew their destination. In their wildest speculations, with guesses from Wake to the Philippines, none had ever said the name Tarawa.

Six days later the first assault waves landed. Nine days later the bloody battle for Tarawa was history.

If you want to place the small solitude of the atoll of Tarawa in the incalculable reaches of the Pacific take your start from San Francisco. Go roughly two thousand nautical miles toward the south-west and youll be at Pearl Harbor on Oahu of the Hawaiian Islands.

You will also be at the hub of the outer line which defends our west coast.

Now start again and travel three thousand more nautical miles along the general route you took from San Francisco and you reach, where they straddle the equator, the Gilbert Islands. One of them, a few degrees north of the line, is the atoll of Tarawa.

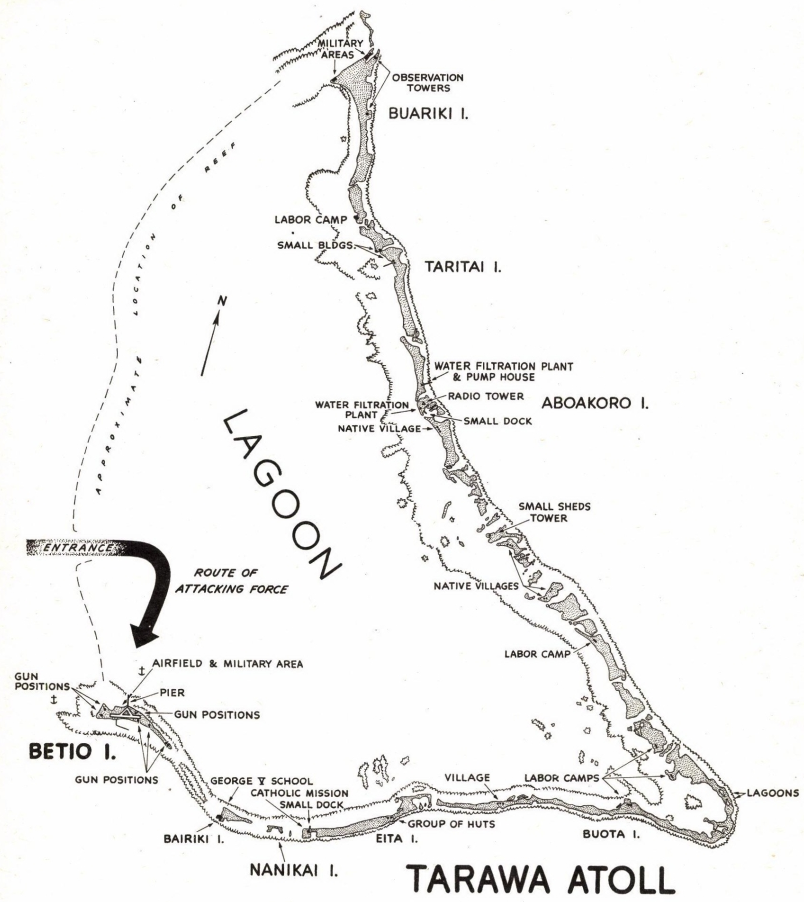

If you looked down on it from the air the atoll would make you think of a lopsided, skinny V, the open ends of which are joined by a reef. The longer arm of this V which stretches toward the north covers eighteen miles, while the bottom arm runs west for twelve.

Its economy consists in a chain of low-lying coral islets separated by sand channels which are fordable at low water. Completely surrounding the seaward side of the atoll is a broad reef. Within the sheltering arms of the V is a lagoon, entered through one small gap in the barrier reef.

You can forget the islets of the atoll with the exception of one. That is Betio, and it lies at Tarawas south-western end. It is a little place, somewhat smaller than New York Citys Central Park. It looks like the profile of a sea horse with a long, tapering tail. With a length of two and a half miles, it is only eight hundred yards across at its widest, and it narrows down to a fraction.

Against this minuscule dot in the immensity of the sea, on November 20, 1943, was hurled the power of the largest Pacific operation to that date. It was an armada composed of battleships, carriers, cruisers, destroyers, transports, subchasers, mine sweepers, and LSTs. And men.

Upon it, this little Betio, was fought one of the bloodiest battles in one hundred and sixty-nine years of Marine Corps history. Of the attacking force three thousand and fifty-six men were either killed, wounded, or missing.

You will wonder why.

The Japanese over a period of fifteen months did a very sound job in perfecting their defenses for the Gilberts, and the heart of their efforts was little Betio. They transformed its flat insignificance into one solid islet fortress which they felt, with considerable justification, would prove impregnable.

For its beaches and the reef were lined with obstaclesconcrete pyramid-shaped obstructions designed to stop landing boats, tactical wire in long fences, coconut-log barricades, mines, and large piles of coral rocks.

And for its beach defense there were numerous weaponsgrenades, mortars, rifles, light and heavy machine guns, 13-mm. dual-purpose machine guns, 37-mm. guns, 70-mm. infantry guns, 75-mm. mountain guns, 75-mm. dual-purpose guns, 80-mm. antiboat guns, 127-mm. twin-mount, dual-purpose guns, 140-mm. coast-defense guns, and 8-inch coast-defense guns.