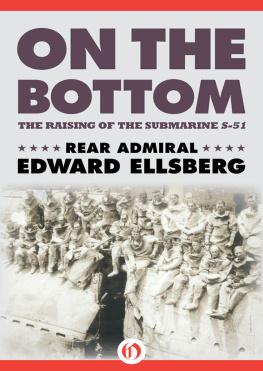

PREFACE

T HE world beneath the sea has always had a peculiar fascination for us mortals, though unequipped ourselves by nature with fins, tails, and gills to explore its watery depths as may the fishes. But our lack of natural equipment has never prevented our imaginations from running riot with the oceans wonders and its treasures, and from ancient days to the present the literature of the deep sea, whether presented as fact or fiction, has mainly been notable for the fantastic tales which adorn it and the unreal terrors and legendary treasures with which authors have strewn the ocean floor.

MEN UNDER THE SEA is the story of real men of several nations and of various centuries who in different parts of the ocean and for diverse reasons have actually battled with the deep sea, sometimes for treasure, sometimes to save others, sometimes to save themselves. Here they are, whether trapped in smashed submarines, dressed in rubber diving suits, cased in ponderous metal armor, or as naked as nature brought them into the world, face to face with the real terrors of the deep. Sometimes they lived and won, sometimes they diedin either case their adventures under the sea need garnishing neither with fabulous monsters nor mythical treasures to make them as gripping to us today as anything evolved in the fertile imaginations of Victor Hugo or Jules Verne or of their more modern imitators.

In some of the struggles related here I took part. In most of the others I have had personal contact with some of the participants and with what took place, and can vouch for the facts, or (as will be noted occasionally) for the lack of them in the instances cited where the public has been gulled by self-styled salvage experts (?) and their glowing tales of wealth beneath the seas to be recovered by their particular diving gadgets.

For details in connection with the Laurentic, I am indebted to Captain G. C. C. Damant, Royal Navy (now retired), who commanded throughout in the unprecedented recovery of $44,000,000 in gold from that wartime victim of German submarine activities.

For data on the Davis lung, for much of the history of diving, and for permission to use certain illustrations from his book DEEP DIVING, thanks are due to Sir Robert H. Davis, manager of Siebe, Gorman & Co., of London, pioneers for over a century in diving developments and equipment.

The illustrations and much of the data on the use of the underwater torch were furnished through the courtesy of Mr. Charles Kandel, manager of the Craftsweld Equipment Corporation of New York.

To Mr. William Wallace Wotherspoon, salvage master on many wrecks in the United States and Canada, I owe my information on the Empress of Ireland.

To the late Lieutenant Alberto Cuniberti, Italian Royal Navy, lamented martyr to the advancement of safety beneath the seas, I owe a debt which can now never be paid for much information on deep diving in armored rigs, and in particular for information on the salvage of the Egypts treasure.

Special thanks are due to Commendatore Giovanni Quaglia, president of Sorima of Genoa, Italy, and to Signor Galeazzo Manzi-F de Riseis, manager of Sorima, for many courtesies while in Genoa, for detailed information, and for their privately printed account (on which my story is mainly based) of Sorimas successful recovery of a huge amount of bullion from the Egypts strong room in by far the deepest salvage job ever attempted by men under the sea.

In this connection, to those interested in a very stirring and completely detailed eye-witness account of the Egypt salvage, I can recommend the two-volume story, SEVENTY FATHOMS DEEP and THE EGYPTS GOLD , by David Scott, correspondent of the London Times, who was present during much of the work on the Egypt.

To Lieutenant Commander C. B. Momsen, U.S.N., I am grateful for data furnished on the Momsen lung now used for submarine escape in the United States Navy, and for the account of our Navys recent experiments in deep diving with helium. To Lieutenants A. R. Behnke and O. D. Yarbrough, Medical Corps, U.S.N., I am obliged for most of the facts on the physiology of lung training and of the physiological effects of helium in deep diving.

Lastly to Commander Henry Hartley, U.S.N., late skipper of the U.S.S. Falcon, and to my old shipmates on the Falcon, who at the risk of their lives unwittingly furnished many of the adventures here related, I owe a deep debt of gratitude. Especially is my appreciation here extended to Chief Bosuns Mate Bill Carr, who in spite of my one lamentable failure to coperate with him, finally and deservedly won the Navy Cross for heroism on the S-4.

E DWARD E LLSBERG .

CHAPTER I

S HROUDED in a web of frayed hawsers and dripping air hoses, a battered submarine, with a ragged gash laying open her port side from deck to keel, rested in the drydock. With her diving fins cocked drunkenly in opposite planes, her conning tower half smashed in, her rudder jammed hard astarboard, and a trickle of mud and water oozing from her stern torpedo tube, that submarine was a dismal sight. Around her, crazily floating half awash in the nearly unwatered drydock, were the eight huge cylindrical pontoons which had floated that wreck in from her ocean bed at the bottom of the cold Atlantic off Block Island, 150 miles away.

Looking down on that submarine from the towering sides of the drydock were the divers who had lifted her and brought her in, their incredulous eyes hardly able yet to believe that actually they saw her there, the submarine S-51, for whose hulk over nine seemingly endless months they had battled the fierce Atlanticthat at last, safely locked in behind the caisson of that drydock holding back the sea, they had that ship where she could not again get away from them and sickeningly slip from their sight back to the ocean depths.

They were a wan group of men, those staring diversweather-beaten, with cracked lips, seamed faces, sunken eyes, and lean bodies from which had been burned every ounce of fat by long hours of breathing excessive oxygen in heavily compressed air forced down to them as they struggled on the ocean floor. For the hundredth time they leaned again over the drydock rails, gazing unbelievingly at the ship they had salvaged. Hopeless their task had seemed when, 22 fathoms down at the bottom of the icy ocean, they first had pitted their puny bodies against the powers of the sea, to lift that 1,200-ton wreck to the surface. Even more hopeless the task had seemed after months of fruitless struggling far offshore, whenin the minds of the divers groping in mud, in darkness, and in frigid coldthe ocean began to take on a definite personality, that of a malignant demon with superhuman cunning and unearthly strength fighting to hold from them what it had claimed as its own. Relentless was the grip, formidable were the weapons of the seaon the surface, fierce gales to batter and to scatter the salvage ships; on the bottom, icy cold water to freeze a man to the very marrow of his bones, the dark solitude of the weird depths to drive cold fear into a mans heart as he struggled alone in the mud and the blackness enfolding that wrecked submarine, a cold fear to paralyze the heart even more than the chilling water ever could paralyze the body, and last and worst of all the terrible pressure of the deep sea enveloping everything, ready instantly to crush a man into jelly under a load of 60 tons should he by any mischance lose the air pressure inflating his suit.