This edition copyright A Vincent McInerney 2011

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84832 096 3

PDF ISBN: 978 1 78346 408 1

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 78346 874 4

PRC ISBN: 978 1 78346 641 2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, including photocopying, recording,

or any information storage and retrieval system, without

prior permission in writing of both the copyright

owner and the above publisher.

The right of Vincent McInerney to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Typeset and designed by M.A.T.S. Leigh-on-Sea, Essex

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, Wiltshire

Editorial Note

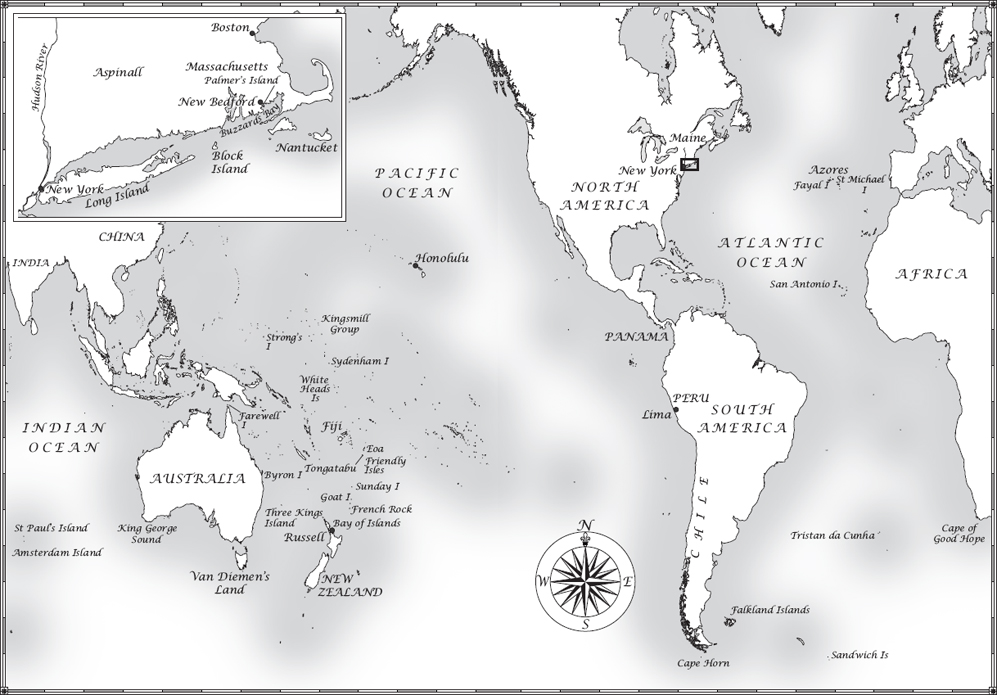

NELSON COLE HALEY seems to have written the initial manuscript account of his life aboard the whale ship, Charles W Morgan, while in Hawaii around the time of his marriage in 1864 there is no evidence as to whether this was from a journal, or from memory. The manuscript then passed into Haleys family. In 1941 the Charles W Morgan was taken over by the Marine Historical Association, Mystic, Connecticut, and newspaper accounts of this came to the notice of Haleys heirs. His daughter, Mrs May Rothwell, of Honolulu, contacted the Marine Association and sent them a typewritten copy of the original manuscript, and eventually presented the original to the Marine Museum in 1944. Within this period the history department at the University of Hawaii also made a copy. After this, there was an edition from Ives Washburn, New York, 1948, and a Robert Hale, London, edition of 1950.

This abridgement of Haleys Whale Hunter is taken from the 1951 edition by the Travel Book Club, London, of approximately 130,000 words, reduced here to 45,000. Losses have been of some slightly repetitious encounters and engagements with the whale and accounts of geographic, topographic, and oceanic descriptive, and explanatory, passages.

Introduction

Except to a few whose minds to them are kingdoms, and others who can hardly be said to have any minds at all, the long monotony of unsuccessful seeking for whales is very wearying.

Nelson Cole Haleys (1832-1900) Whale Hunter is a classic and authentic first-hand account of a four-year voyage aboard the famous American whaler Charles W Morgan. It is both a compelling seamans yarn and an important source of information on the great days of American whaling during the middle years of the nineteenth century when whales were the source of oil and fuel to a nascent industrial nation. The New England whalers sailed far into the South Pacific in their search for whales and Haleys evocations of the exotic places they saw are as potent as his descriptions of the dangerous whale hunts he experienced as a harpooner.

The book is set during the zenith of a fishery whose And by Acts of Parliament in 1315 and 1324, it was promulgated that any whales cast/washed ashore or taken in the sea would, naturally, belong to the king.

Scoresby tells us that the first organised English whaling attempt was made in the year 1594. A fleet of ships, including the Grace of Bristol, were fitted out for Cape Breton. In this area they took on board 700 or But over-fishing saw the shoal-water coasts of Sptizbergen and Greenland soon depleted of inhsore whales, and fishing had to move to deeper waters relatively far from land. This meant that now the trying out, or extraction of oil, needed to be performed at sea on board ship, which became standard practice.

It soon became apparent that just as, nowadays, pig farmers claim that the only unusable part of the pig is the squeal, so eventually all of the whale would be processed except the spout. Oil for light, heat and fire, meat and whalebone (used in much the same way as plastic today) were the commodities first extracted, and Britain was right at the forefront. Such was the importance of the industry in the mid-eighteenth century that a bounty of 40 shillings for every ton, when the ship was 200 tons, or upwards, was given to the crews of ships engaged in that business in the Greenland seas, If they made it there, an oath sworn by a particular ships owners that the sailors concerned were of a particular ships crew would act as a safeguard and buy them an uneasy reprieve.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the northern seas were providing fewer fish, while the Industrial Revolution was gathering pace, with its corresponding demands for oils for light, and for lubricating and cooling fluids. Whales around the Grand Banks had become scarce, while Britain imposed prohibitive duty on American whale oil. What has been described as the golden age of American whaling began with the commencement of the commercial exploitation of the Pacific grounds in the 1830s after the Ganges, a Nantucket whaler, caught the first right whale off the northwest coast of America. The earlier discovery of whales out in the warm South Pacific, where whalers could fish for three years at a time rather than just through the short Arctic summer in the North Atlantic fishery, was to prove a boon for the American whaling ports.

Captain Coffin of Nantucket, in about 1773 was invited to tell the British Parliament all he knew about certain monstrous creatures in southern regions, that is, about whales and whaling. Captain Coffin, like the Ancient Mariner, told his tale, from which it emerged that Nantucket ships were already active in and around the Falkland Islands, and were cautiously venturing around both capes, Horn and Good Hope, into inviting and fertile seas. These ventures to the Falklands and beyond seem to have been the beginning of southern whaling for the New England ports, and by the time of Haleys voyage on the Charles W Morgan during the years 1849-1853, Nantucket and New Bedford (where the Charles W Morgan currently lies restored) were, by many, considered the epicentre of the American whaling industry, an industry so huge that posters were displayed up and down the northeast seaboard inviting recruits. The anonymous author of Adventures of a Sailor gives an example:

LANDSMEN WANTED! ONE THOUSAND STOUT YOUNG MEN WANTED for the fleet of whale-ships now fitting out for the North and South Pacific Fisheries. Extra chances given to Coopers, Carpenters and Blacksmiths. None but industrious young men, with good recommendations, taken. Such will have superior chances for advancement. Outfits furnished to each individual, before proceeding to sea. Persons desiring of availing themselves of the present

This unknown author goes on to state: They are the lures by means of which farmers lads, and factory and city boys, are drawn into the net of the shipper of crews for whalers. That is, what the owners and agents wanted, ideally, were non-seamen (except for the officers and boat-steerers, carpenters, coopers, etc.) for their crews. A real, before-the-mast tar would be refused a place, being thought too footloose and too ready to desert, and to be impossible to discipline and control over the course of a three or four year voyage. Whalers were not vessels that demanded great seafaring experience. Usually, ships, like hospitals, do not close at night, but whalers would often drop sails come the dark, and lie to. Their work was done by daylight and, once on the fishing grounds, there was no need to go any further. No, the ideal candidate for the pulling of ropes and oars, and the wielding of the mop and bucket, was the sort of landsman that Haley describes appearing on deck at the