SKETCHES FROM MY LIFE.

CHAPTER I.

A ROUGH START IN LIFE.

To attempt to write and publish sketches of my somewhat eventful career is an act that, I fear, entails the risk of making enemies of some with whom I have come in contact. But I have arrived at that time of life when, while respecting, as I do, public opinion, I have hardened somewhat into indifference of censure. I will, however, endeavour to write as far as lies in my power (while recording facts) 'in charity with all men.' This can be done in most part by omitting the names of ships in which and officers under whom I have served.

I was born, as the novelists say, of respectable parents, at Walton-on-the-Wold, in Leicestershire, on April 1, 1822. I will pass over my early youth, which was, as might be expected, from the time of my birth until I was ten years of age, without any event that could prove interesting to those who are kind enough to peruse these pages.

At the age of ten I was sent to a well-known school at Cheam, in Surrey, the master of which, Dr. Mayo, has turned out some very distinguished pupils, of whom I was not fated to be one; for, after a year or so of futile attempt on my part to learn something, and give promise that I might aspire to the woolsack or the premiership, I was pronounced hopeless; and having declared myself anxious to emulate the deeds of Nelson, and other celebrated sailors, it was decided that I should enter the navy, and steps were taken to send me at once to sea.

A young cousin of mine who had been advanced to the rank of captain, more through the influence of his high connections than from any merit of his own, condescended to give me a nomination in a ship which he had just commissioned, and thus I was launched like a young bear, 'having all his sorrows to come,' into Her Majesty's navy as a naval cadet. I shall never forget the pride with which I donned my first uniform, little thinking what I should have to go through. My only consolation while recounting facts that will make many parents shudder at the thought of what their children (for they are little more when they join the service) were liable to suffer, is, that things are now totally altered, and that under the present rgime every officer, whatever his rank, is treated like a gentleman, or he, or his friends, can know 'the reason why.'

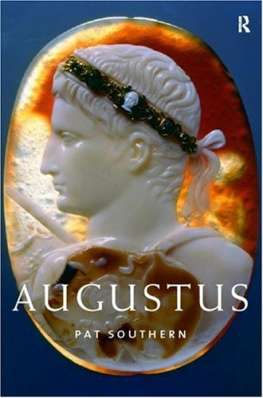

I am writing of a period some fifteen or twenty years after Marryat had astonished the world by his thrilling descriptions of a naval officer's life and its accompanying troubles. At the time of which I write people flattered themselves that the sufferings which 'Midshipman Easy' and 'The Naval Officer' underwent while serving the Crown were tales of the past. I will show by what I am about very briefly to relate that such was very far from being the case.

Everything being prepared, and good-bye being said to my friends, who seemed rather glad to be rid of me, I was allowed to travel from London on the box of a carriage which contained the great man who had given me the nomination (captains of men-of-war were very great men in those days), and after a long weary journey we arrived at the port where H.M.S. was lying ready for sea. On the same night of our arrival the sailing orders came from the Admiralty; we were to go to sea the next day, our destination being South America.

Being a very insignificant individual, I was put into a waterman's boat with my chest and bed, and was sent on board. On reporting myself, I was told by the commanding officer not to bother him, but to go to my mess, where I should be taken care of. On descending a ladder to the lower deck, I looked about for the mess, or midshipmen's berth, as it was then called. In one corner of this deck was a dirty little hole about ten feet long and six feet wide, five feet high. It was lighted by two or three dips, otherwise tallow candles, of the commonest descriptionbehold the mess!

In this were seated six or seven officers and gentlemen, some twenty-five to thirty years of age, called mates, meaning what are now called sub-lieutenants. They were drinking rum and water and eating mouldy biscuits; all were in their shirtsleeves, and really, considering the circumstances, seemed to be enjoying themselves exceedingly.

On my appearance it was evident that I was looked upon as an interloper, for whom, small as I was, room must be found. I was received with a chorus of exclamations, such as, 'What the deuce does the little fellow want here?' 'Surely there are enough of us crammed into this beastly little hole!' 'Oh, I suppose he is some protg of the captain's,' &c. &c.

At last one, more kindly disposed than the rest, addressed me: 'Sorry there is no more room in here, youngster;' and calling a dirty-looking fellow, also in his shirtsleeves, said, 'Steward, give this young gentleman some tea and bread and butter, and get him a hammock to sleep in.' So I had to be contented to sit on a chest outside the midshipmen's berth, eat my tea and bread and butter, and turn into a hammock for the first time in my life, which means 'turned out'the usual procedure being to tumble out several times before getting accustomed to this, to me, novel bedstead. However, once accustomed to the thing, it is easy enough, and many indeed have been the comfortable nights I have slept in a hammock, such a sleep as many an occupant of a luxurious four-poster might envy. At early dawn a noise all around me disturbed my slumbers: this was caused by all handsofficers and menbeing called up to receive the captain, who was coming alongside to assume his command by reading his official appointment.

I shall never forget his first words. He was a handsome young man, with fine features, darkened, however, by a deep scowl. As he stepped over the side he greeted us by saying to the first lieutenant in a loud voice, 'Put all my boat's crew in irons for neglect of duty.' It seems that one of them kept him waiting for a couple of minutes when he came down to embark. After giving this order our captain honoured the officers who received him with a haughty bow, read aloud his commission, and retired to his cabin, having ordered the anchor to be weighed in two hours.

Accordingly at eight o'clock we stood out to sea, the weather being fine and wind favourable. At eleven all hands were called to attend the punishment of the captain's boat's crew. I cannot describe the horror with which I witnessed six fine sailor-like looking fellows torn by the frightful cat, for having kept this officer waiting a few minutes on the pier. Nor will I dwell on this illegal sickening proceeding, as I do not write to create a sensation, and, thank goodness! such things cannot be done now.