DUDLEY POPE

Governor Ramage RN

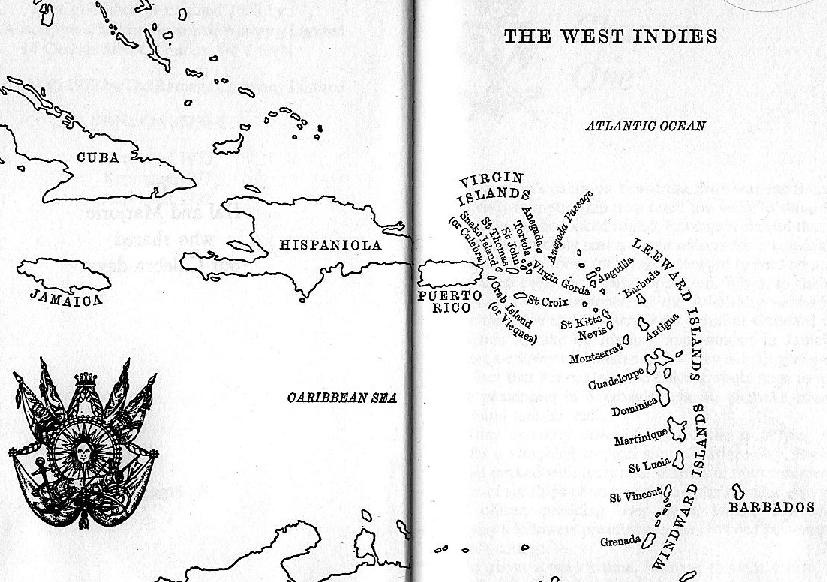

The captain's cabin on board the Lion was small, even for an old sixty-four-gun ship now rated too weak to stand in the line of battle. As he looked round, Ramage reckoned that at most it could comfortably seat a dozen officers for a convivial evening and still leave room for an agile steward to haul on a corkscrew and keep everyone's glass topped up. When, in their wisdom, the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty suddenly decided that the Lion should carry Rear-Admiral Goddard across the Atlantic to take up his new appointment in Jamaica - and escort a convoy at the same time - they did not give a thought to the fact that her captain and officers would have to move over, like passengers in a crowded coach, to make room for the Admiral and his staff.

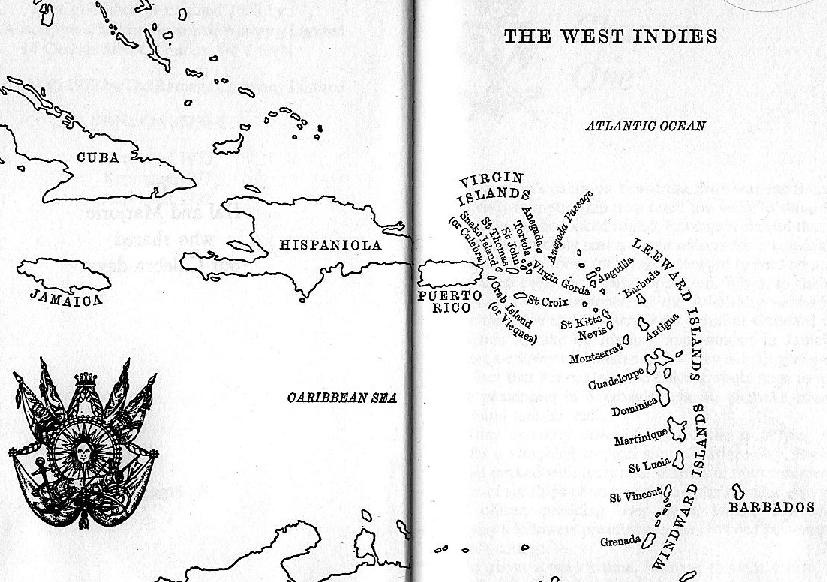

They certainly never visualized the ship lying at anchor under a scorching tropical sun in Carlisle Bay, Barbados, the cabin packed with forty-nine masters of merchantmen, the captains of six ships of war, and the Admiral. Her own commanding officer, presiding over them, looked like one of Mr Wesley's followers preaching in the crowded parlour of a fisherman's cottage.

In about a week's time, Ramage thought sourly, it'll dawn on Captain Croucher that he could have held this convoy conference up on deck under the big awning, or in any one of a dozen buildings on shore in Bridgetown; but among his other shortcomings Captain Aloysius Croucher lacked imagination -and was so thin there was probably not enough meat on him to notice any difference between tropical heat and arctic cold.

Ramage guessed that Captain Croucher's mind was fully occupied with two considerations: relief at having brought the convoy safely across the Atlantic to Barbados, and the need to make sure that the masters of the merchant ships understood that here fresh frigates took over as escorts for the last leg of the voyage, westward across the Caribbean to Kingston, Jamaica.

For a variety of reasons the next and shortest section of the voyage was by far the most dangerous. It was obvious to Ramage that, unlike Captain Croucher, the masters of the merchantmen had only one idea in their minds: to stop him talking so they could get out of this furnace-like cabin as quickly as possible and cool off on deck, where a brisk Trade wind breeze was blowing.

The canvas covering the planking underfoot was painted chessboard fashion in black-and-white squares and the masters, slumped in canvas-backed chairs from the officers' cabins or hunched uncomfortably on narrow forms brought up from the messdeck, reminded Ramage of a jumbled set of pawns. The simile amused him because Captain Croucher made a perfect bishop.

Croucher tugged at the lapels of his coat in an attempt to make the shoulders sit squarely. Although the Captain's tailor had obviously worked hard, all his artful skill with scissors and thread could not disguise the fact that nature had sold Croucher short: a bonus of half a hundredweight of flesh would not have stopped him from looking like a skeleton wrapped in parchment. No wonder the seamen, with their unerring instinct for the apt and ambiguous nickname, called him "The Rake". He was every man's idea of the prosecutor at an Inquisition trial. He had the features of a fanatic, and one could imagine him fervently condemning a heretic to hellfire and damnation amidst a welter of prayers and exhortations. Or perhaps he could even be the victim; a few hours' torture on the rack might leave a man as long and thin.

The bone of Croucher's brow protruded so much that the deep-set grey eyes looked like a lizard glaring out from under a ledge of rock. His hands and wrists were so skinny they would pass muster for lizard's claws. Was he married? What sort of woman could love a man like this? Even the thought was repellent.

If Croucher was the bishop on this bizarre chessboard, then Jebediah Arbuthnot Goddard, Rear-Admiral of the White, was the knight, Ramage mused. Being prevented by the rules from going in a straight line would not worry him: Goddard always chose the devious route instinctively and would find the knight's dog-leg move, two forward and one sideways, no hindrance.

Croucher's voice was as monotonous and unavoidable as the drip from a leaking deck in a seaway, but even more depressing. He was giving his instructions to the masters like a weary and disillusioned parson delivering a sermon written by his wife and castigating something he secretly liked. From time to time he glanced nervously at Goddard, who was sitting to one side, as plump as Croucher was thin: a pink frog squatting grossly at the edge of a pond. Perspiration trickling down the creases of his bulging neck was rapidly reducing the starched neatness of his lace stock to a necklet of overcooked lasagna. Goddard frequently mopped his face with a handkerchief which he occasionally tossed to a young and pimply lieutenant, who replaced it with a fresh one from a bag beneath his chair. Nor did the Admiral attempt to hide his boredom, yawning every few minutes and removing the diamond pin from his stock for inspection by the glare of the sea reflected through the stern lights.

The cabin was comfortably furnished. The fitted racks above the mahogany sideboard on the larboard side held silver-lidded claret jugs and several square-sided, cut-glass decanters. On the sideboard itself, out of place in such company, was a large silver tea urn. Heavy, dark-blue and gold brocade curtains hung down each side of the stern lights and the covers of four armchairs were of the same pattern. On the starboard side a large, highly polished mahogany wine cooler had a silver plaque on the side, and the rack above it held four rows of cut-glass tumblers, each sparkling as flashes of sunlight reflected up from the water through the stern lights. Other racks held an elaborate fighting sword, the leather scabbard inlaid with silver tracery and the basket handle of an unusual design. Below it was a dress sword with a black scabbard and sword knots of heavy bullion that would cost at least five hundred guineas from Mr Prater, the sword cutler in Charing Cross.

The whole cabin, formerly Croucher's and now Goddard's, showed that its present occupant was a man of wealth and, Ramage had to admit, of taste. The only hint that it was the cabin of a warship came from the heavy guns on each side, squatting like great bulldogs, the barrels and breeches gleaming black and the carriages painted dull yellow. The thick rope breeching and train tackles had been scrubbed and the blocks sanded and varnished until they gleamed.

The masters, oblivious to the Admiral's taste, were a motley group. Some had the weather-worn appearance and four-square stance of working seamen - obviously their ships were small, with crews to match, and they weren't above tailing on the end of a rope when needed. Others were well dressed; the masters of "established" ships trading regularly across the Atlantic and whose tailors had made them clothes of cooler, lightweight material.

The uniforms of the naval officers made no concession to the climate, and since they were visiting the flagship they were dressed in frock coats and white breeches, with swords. Each of the three frigate captains wore a plain gold epaulet on the right shoulder showing he had less than three years' seniority.

The two lieutenants were a complete contrast to each other. Lieutenant Henry Jenks, commanding the Lark lugger, was in his late twenties, sandy-haired and plump, with a cheerful face turned a deep red by the sun. A white band of skin across his brow just below the hair-line showed he rarely went out in the sun without wearing his hat. Alone among the naval officers, his hat was of the old style, cocked on three sides, instead of the newly introduced hat cocked on only two.