H ISTORICAL F ICTION BY D UDLEY P OPE PUBLISHED BY M C B OOKS P RESS

Ramage

Ramage & The Drumbeat

Ramage & The Freebooters

Governor Ramage R.N.

Ramages Prize

Ramage & The Guillotine

Ramages Diamond

Ramages Mutiny

Ramage & The Rebels

The Ramage Touch

Ramages Signal

Ramage & The Renegades

Ramages Devil

Ramages Trial

Ramages Challenge

Ramage at Trafalgar

Ramage & The Saracens

Ramage & The Dido

Published by McBooks Press 2003

Copyright 1987 by Dudley Pope

First published in England 1987 by

The Alison Press/Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd, London

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the publisher. Requests for such permissions should be addressed to McBooks Press, Inc., ID Booth Building, 520 North Meadow St., Ithaca, NY 14850.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pope, Dudley.

The devil himself : the mutiny of 1800 / by Dudley Pope.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 1-59013-035-9 (alk. paper)

1. Danae (Ship) 2. Napoleonic Wars, 1800-1815--Naval operations, British. 3. Napoleonic Wars, 1800-1815--Naval operations, French. 4. Mutiny--Great Britain--History--19th century. 5. Great Britain. Royal Navy--History--19th century. 6. France--History, Naval--19th century. I. Title.

DC153.P73 2003

940.2745--dc21

2002155901

Visit the McBooks Press website at www.mcbooks.com.

Printed in the United States of America

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

For Kay

kindly critic, patient translator, but never a mutineer!

Contents

Index

Authors Note

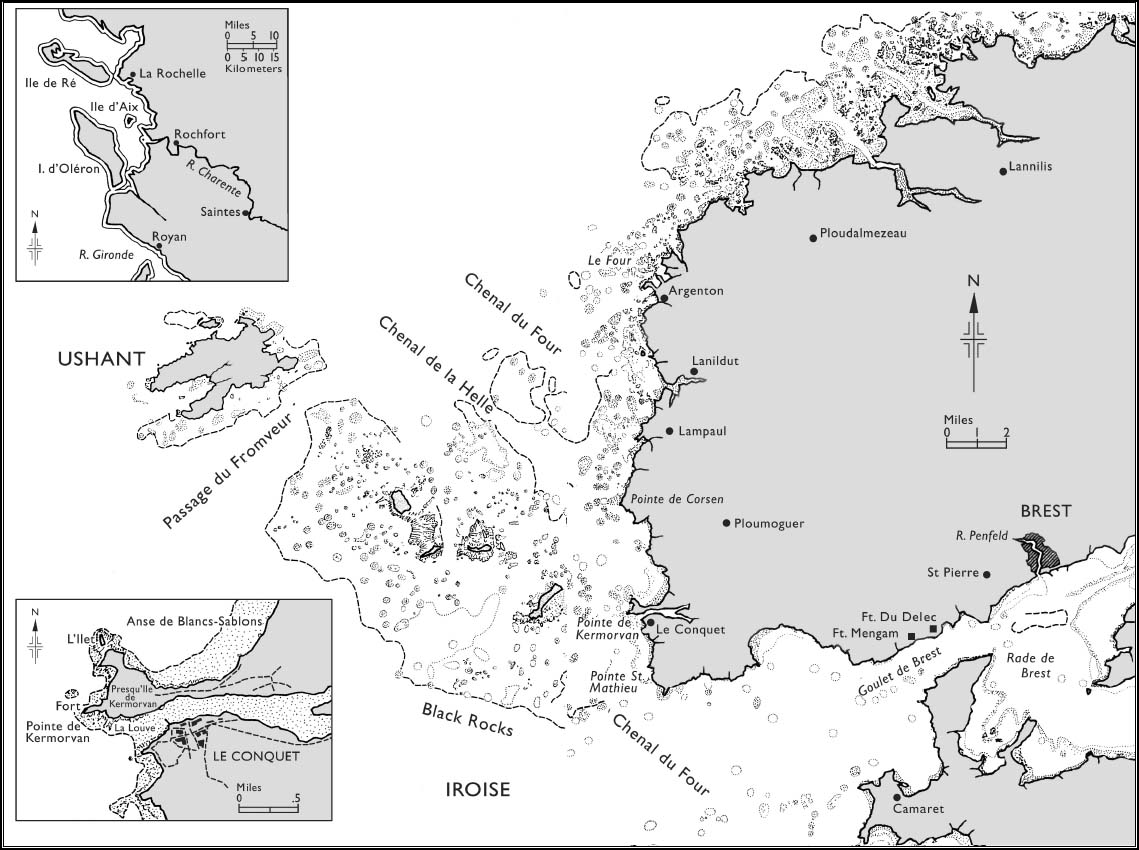

I N THE ARCHIVES at the walled naval headquarters in Brest is a folder labelled Le Diable Lui-mme (the Devil Himself). It dates from March 1800, and no one knows who gave it that name, but the story emerging from the archives (and those in the Public Record Office in London) is intriguing and poses the question: when was a man an American?

D UDLEY P OPE |

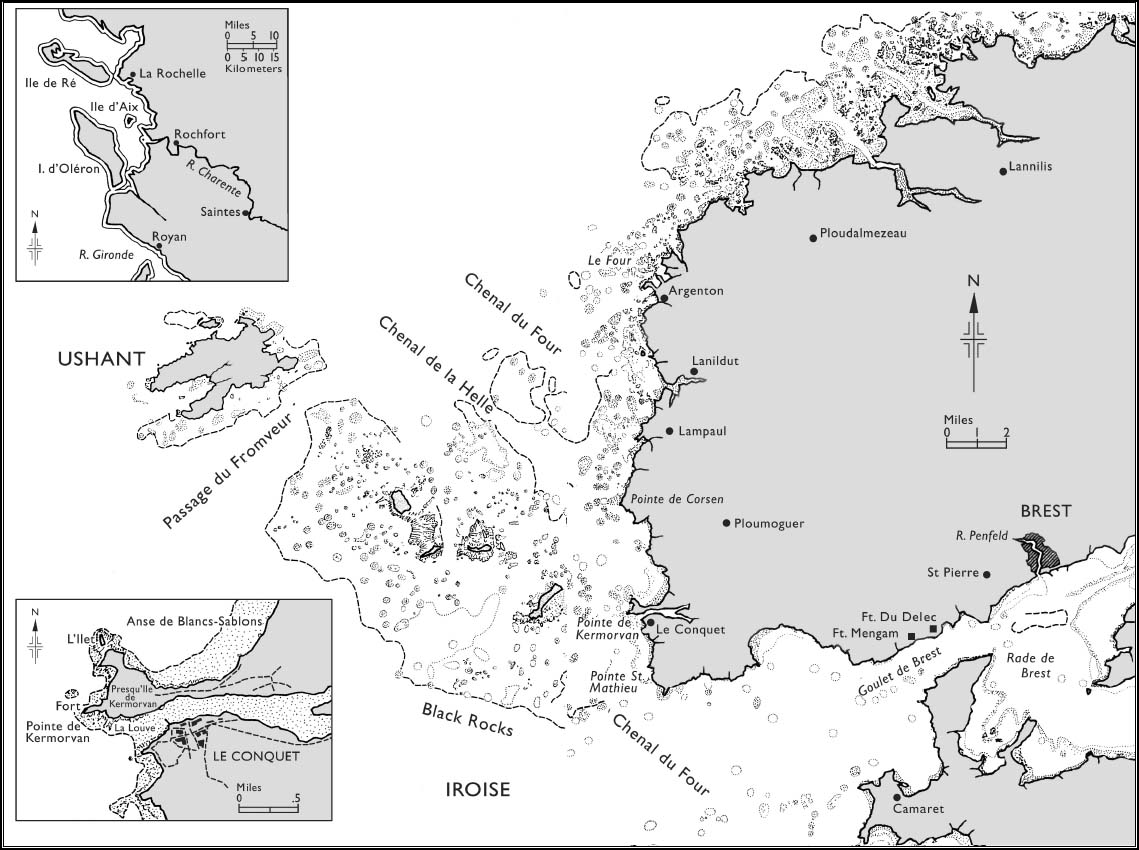

F RENCH A NTILLES |

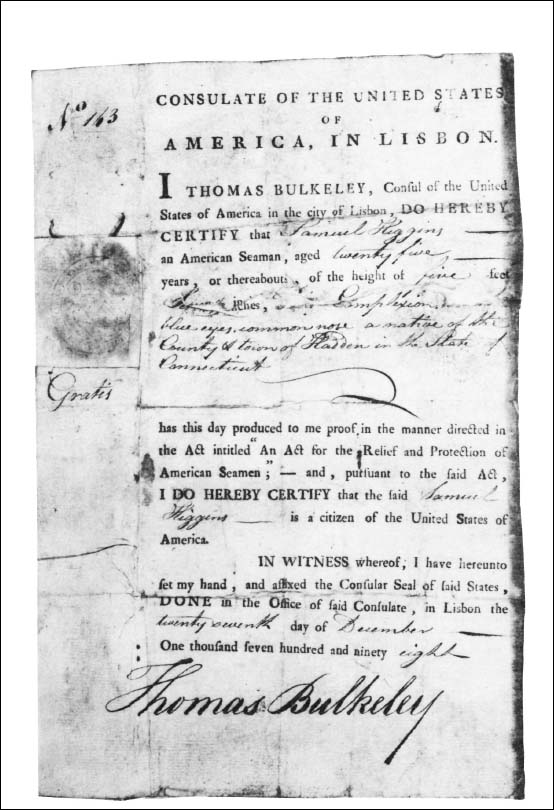

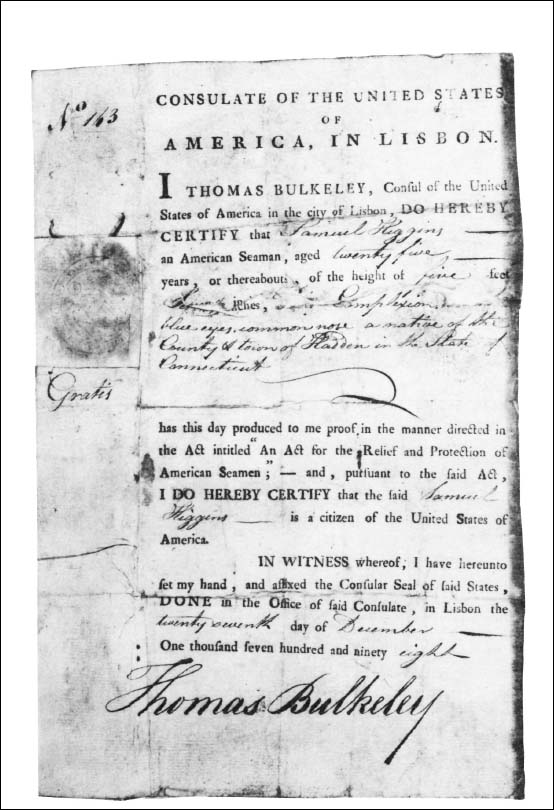

The American Protection form which was produced at a court martial. (Courtesy of Public Record Office, ADM 1/5356)

Preface

T HIS IS THE STORY of a mutiny in the British frigate Danae at the turn of the eighteenth century. The reason for the mutiny will never be known for certain, but it is notable because, along with the story of the Hermione in the West Indies, it was the only case in a war lasting nearly a quarter of a century of a crew mutinying, seizing a frigate and carrying her into an enemy port (where they were distrusted and meagrely rewarded).

The great mutinies of the Fleet at Spithead and the Nore some years earlier had resulted in improvements of the conditions under which the seamen lived. However, unlike the Hermione, which had a sadistically cruel captain whose murder by his crew can raise little sympathy, the mutiny in the Danae focuses on two other problems the Navy faced during the whole war: the pressing of men generally, and in particular the pressing of men claiming to be Americans and who held Protections.

The question of Americans and Protections is dealt with in . However, it must be remembered that the strength of the Royal Navy during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars rested on the press gangs. By 1800 the Royal Navy comprised 110,000 seamen and 20,000 Marines out of a total population of less than nine million. The Navy was in competition with the Army for men, but both were at a disadvantage compared with France, which had universal conscription.

Apart from small parties sent out by individual ships, the press gangs were operated by the Impress Service, which had headquarters in various towns. At the beginning of the war only men connected with the sea were seized, but later any man who appeared to be over eighteen and under fifty-five could be taken. A few classes of men were exemptedfor example farm labourers, especially at harvest time, when each was given a certificate showing he was not liable. Gentlemen, using their dress as a yardstick, were usually exempted by the gangs, which found that jails and the assizes yielded plenty of men: the justices were only too pleased to give offenders the choice of going to sea or going to jail. However, this did not mean that the press gangs supplied the Navy with hardened criminals: men were sent to jail for a wide variety of offences, many quite minor, and a man brought to court for poaching could find himself at sea serving in a ship of the line within the month.

There was one universal rule: once the man was pressed into the Navy he would serve as long as the war continued. A soldier was in the same position. Many men were freed briefly during the few months of peace following the Treaty of Amiens but were pressed again as soon as the war restarted.

The press gang was of course nothing new. Centuries earlier, before the Royal Navy was established, the Cinque ports had to supply ships and men for the countrys defence, and the press was well known to Shakespeare. He has Falstaff, in Henry IV, Part One, admitting that he had misused the Kings press damnably: he had impressed men for the Army and then freed some (especially bachelors about to be married) when bribed. I have got, in exchange of a hundred and fifty soldiers, three hundred and odd pounds, the old villain admitted, saying that he pressed none but good householders, but to make up the numbers had to take up revolted tapsters and ostlers trade-falln; the cankers of a calm world and a long peace

The treatment of a man after he had volunteered or been pressed into the Navy could be harsh if he misbehaved, although the system was fair inasmuch as every volunteer was paid a bounty of 5, and every pressed man was always given the chance of volunteering when he boarded a ship, so that he received the bounty.

Flogging was common, but it must be remembered that this was a harsh age, and it is absurd to judge it nearly two centuries later by modern humanitarian standards. Lashes were awarded in dozens, a dozen being the usual punishment for drunkenness. A captain was not supposed to award more than two dozen lashes, but when the offence deserved more and the captain could not appeal to higher authority (a process which could take months and involve a court martial) the limit was often ignored. The lash was used universally the Army flogged miscreants, and the lash was as well known in the French Navy and Army as the British.

More severe punishments such as hanging were rare: all ships at all times were short of men, and the noose was reserved almost entirely for mutiny or treason. Keel-hauling was never performed in the Royal Navyit is a part of mythology, like pirates making their victims walk the plank (why bother when it was easier to throw the victim over the side?).

Next page