Published by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre, 3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

Email:

www.introducingbooks.com

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Everything that exists is born for no reason, carries on living through weakness, and dies by accident.

Existentialism, a way of looking at experience which Sartre made famous, was the attempt to draw all possible conclusions from the fact that there is no God. Man, he wrote in 1943, is a useless passion. But he is also condemned to be free.

The Early Years

Jean-Paul Sartre, the French philosopher, playwright, novelist, essayist and political activist, was born in Paris on 21 June 1905. His mother, ne Anne-Marie Schweitzer, was 23 years old, and his father, Jean-Baptiste, the son of a country doctor, 31.

On 17 September 1906, Jean-Baptiste Sartre, a naval officer, died of a fever contracted in Cochinchina.

His widow, without means of earning her own living, had to go back to live with her family.

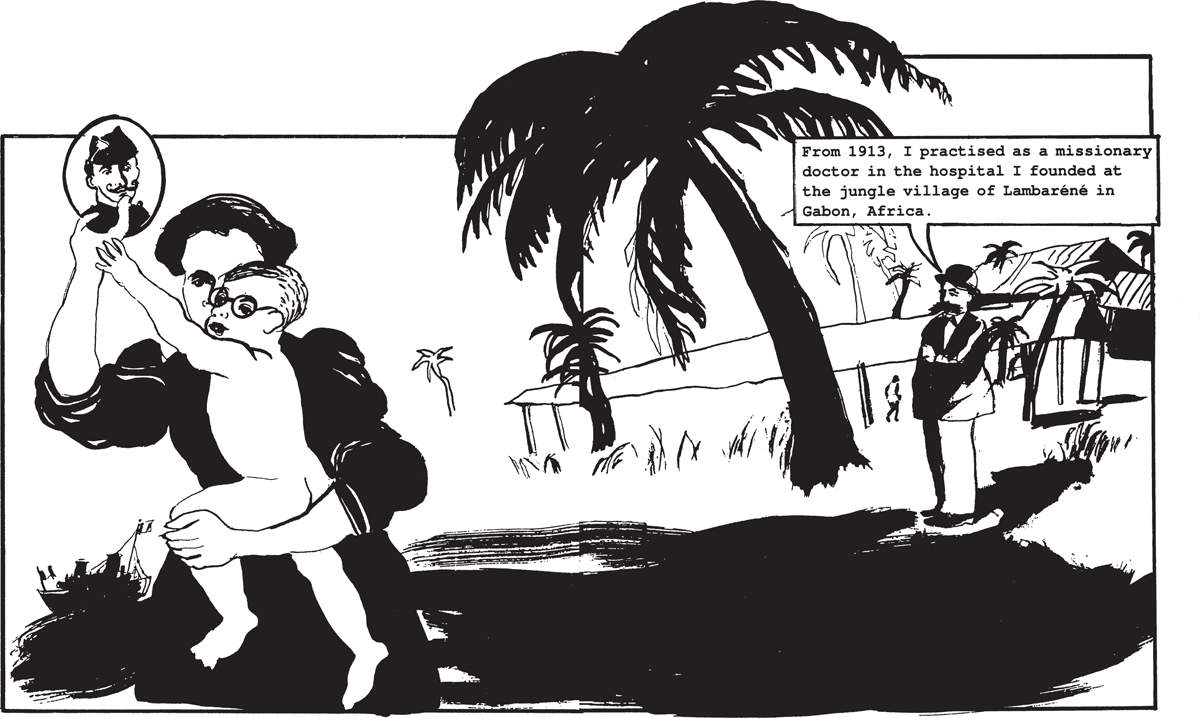

From 1913, I practised as a missionary doctor in the hospital I founded at the jungle village of Lambarn in Gabon, Africa.

Sartres origins, like those of Roland Barthes (191580), are Protestant, and this might explain his sense of being an outsider in a largely Catholic France. His maternal grandfather Charles Schweitzer was uncle to the famous Bach scholar, musician, theologian and Christian missionary Albert Schweitzer (18751965).

In 1963, Sartre published a biographical essay, Les Mots (Words). It tells the story of what he presented as a lonely and unhappy childhood, isolated from other children.

I was kept at home because of the selfish and possessive attitude of my grandfather, Charles Schweitzer.

In 1917, his mother remarried, choosing as her second husband an old admirer, Joseph Mancy.

We know little of this second husband, with whom Sartre did not get on, except that he had earlier not seen himself as capable of offering Anne-Marie the kind of lifestyle which he thought she deserved.

Now that I began to make a career for myself as an engineer, I proposed marriage and took Anne-Marie and her son to live with me in La Rochelle.

For the first time in his life, in La Rochelle, Sartre began to go regularly to school. Once at school, perhaps understandably, Sartre did not get on well with his fellow pupils.

I tried to buy their friendship by offering them treats paid for with money stolen from my mothers purse.

Academically, however, he had few problems, apart from a reluctance to concentrate on the mathematics which his stepfather saw as essential to the career as an engineer which he wished to see him follow. Joseph Mancy did not himself enjoy a particularly successful career and actually went bankrupt.

In 1920, Sartre returned to Paris to study first at the prestigious lyce Henri IV, then the lyce Louis le Grand, a school with a high success rate in preparing students for the competitive examinations required for entry into one of the grandes coles. In 1924, he competed successfully to enter the cole Normale Suprieure, the most famous of all French institutes of higher education for the study of literature and philosophy, and he stayed till 1928.

I became very critical of French society and the highly litist system in which I was being educated.

The principal function of the cole Normale Suprieure was to prepare students for the competitive examination known as the Agrgation, the essential step in any successful teaching career in France. Candidates successful in this examination enjoy higher pay and shorter hours of work than their less well-qualified colleagues. Then, as now, all pupils in the higher forms of the lyces were required to study philosophy.

It is my aim to become a philosophy teacher.

After having, to everyones surprise, failed at his first attempt at the Agrgation de philosophie in 1928, Sartre was more successful in 1929. He came first, followed in the competition, in second place, by Simone de Beauvoir.

The Beaver

Simone de Beauvoir (190886) later wrote of her feelings for Sartre at this time in the first volume of her autobiography, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter (1958).

I met the Beaver earlier in 1929 at the Sorbonne.

I knew when I left him to go home at the end of that academic year that he would never be out of my life.

Although Sartre and the Beaver (his nickname for her) never married, they would indeed become lifelong partners.

Military Service

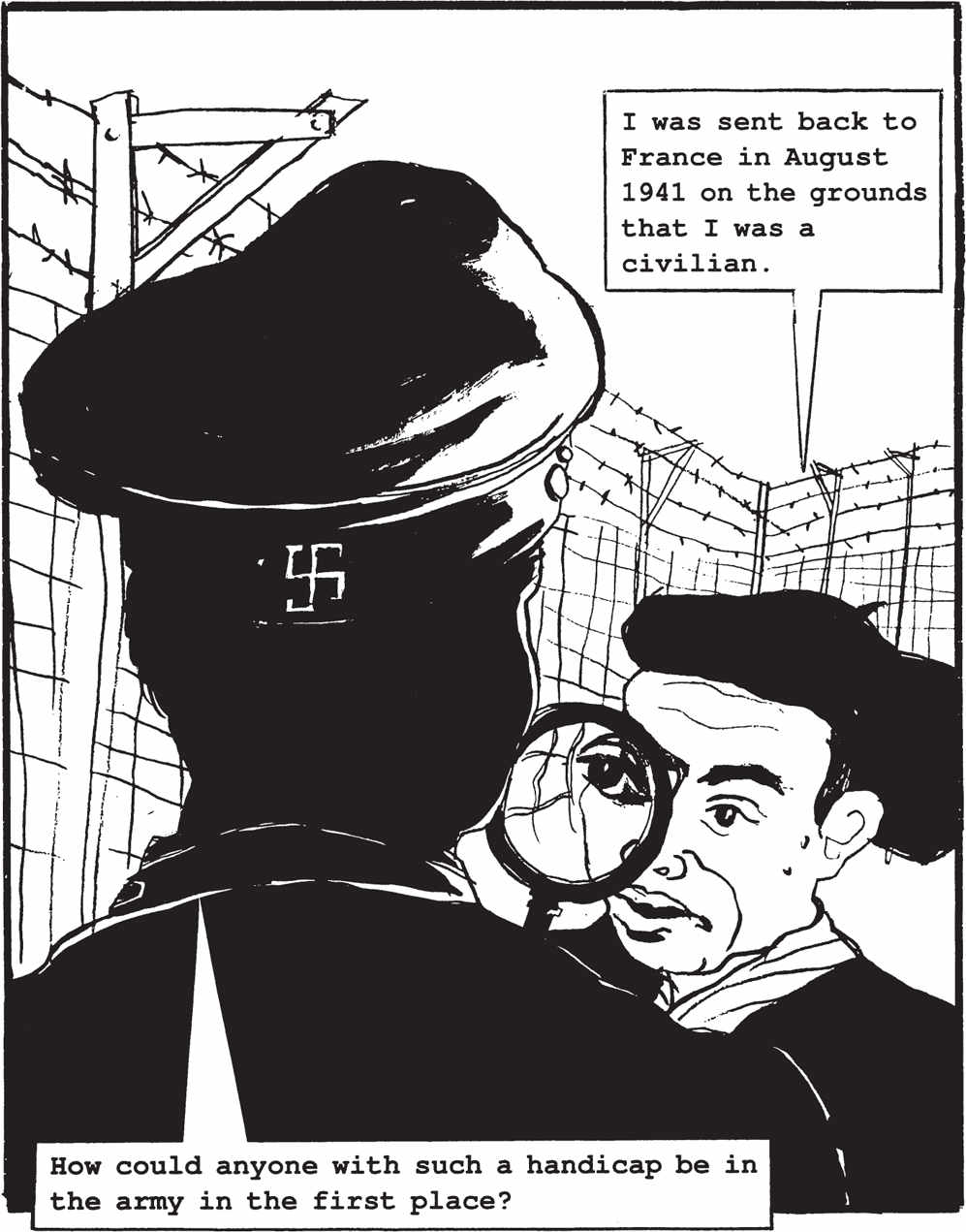

Before Sartre could take up the teaching post to which he was now entitled, he had to do his military service. It is an indication of what the French call la dnatalit franaise (an undesirably low birth-rate) that although Sartre was virtually blind in his left eye, he was not exempted on medical grounds and was called up again at the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. Like a million-and-a-half other French soldiers, he was taken prisoner in the summer of 1940.

I was sent back to France in August 1941 on the grounds that I was a civilian.

How could anyone with such a handicap be in the army in the first place?

Sartre was not, however, either in 1929 or in 1939, expected to be a fighting soldier, and was put into the meteorological section. By an odd coincidence, his instructor was another French philosopher whom he already knew,