M OST PEOPLE TODAY WOULDNT CLASSIFY MILK AS A HEALTH HAZARD . To us, its an innocuous form of nutrition, poured over cereal or consumed with cookies. Milk was not always so innocuous, though. Only a century ago, it was a leading cause of food-borne illness in the industrialized world. Drinking cows milk is not inherently dangeroushumans have been doing so for millenniabut it becomes dangerous if too much time has passed between when the milk is collected and when the milk is consumed. Milk is typically consumed without heating, and heat is what kills the bacteria inherent in our food. Milk is also high in sugar and fat, which makes it a perfect medium for bacterial growth. The negligible amount of bacteria present in milk when it is collected grows exponentially with each passing houra biological fact that milk consumers never really grappled with until the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

The industrial revolution changed the landscape of where people worked and thus where they lived. As the population of Europe and the United States shifted from the country (where people worked on farms) to the city (where they worked in factories), people no longer lived close to the cows that produced their milk. Dairy farmers began transporting milk farther and farther from its source, which meant that people began drinking milk longer and longer after it had been collected. century was, according to one medical expert, as deadly as Socrates hemlock.

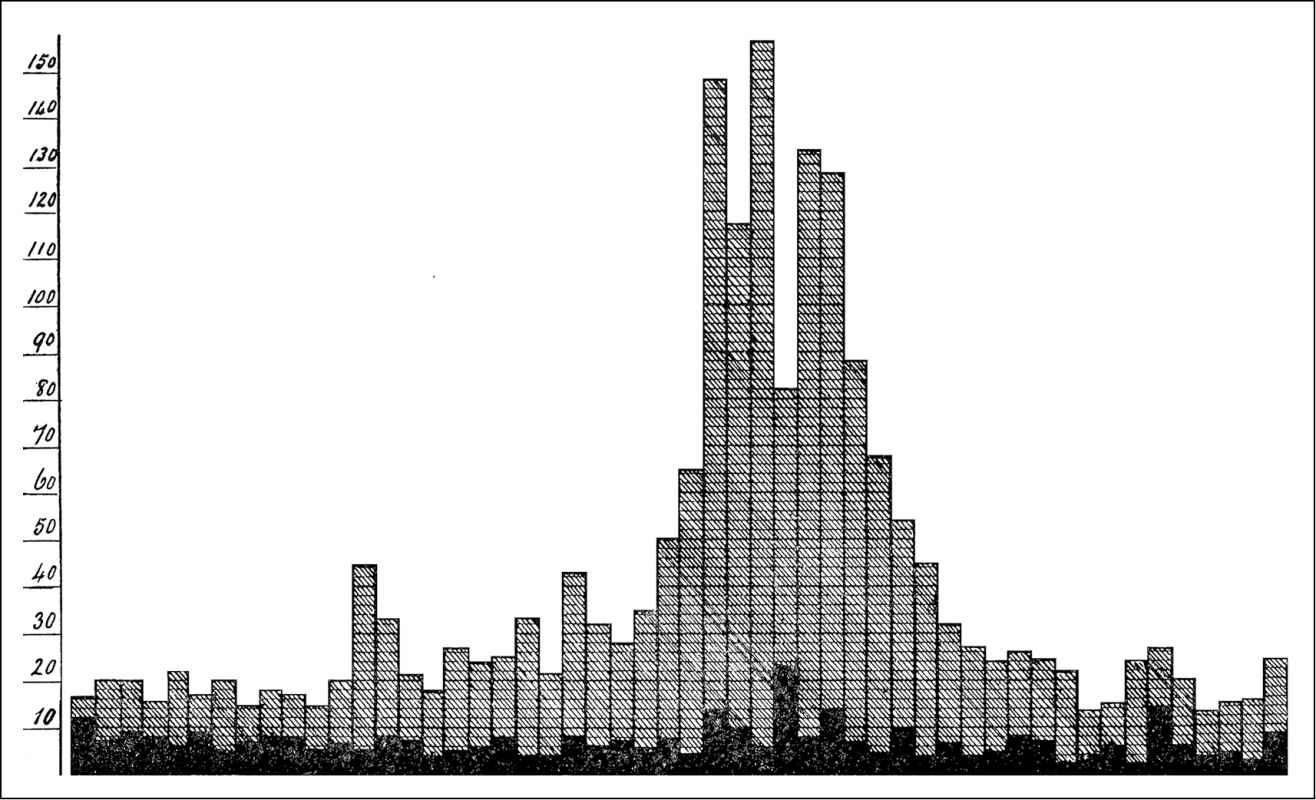

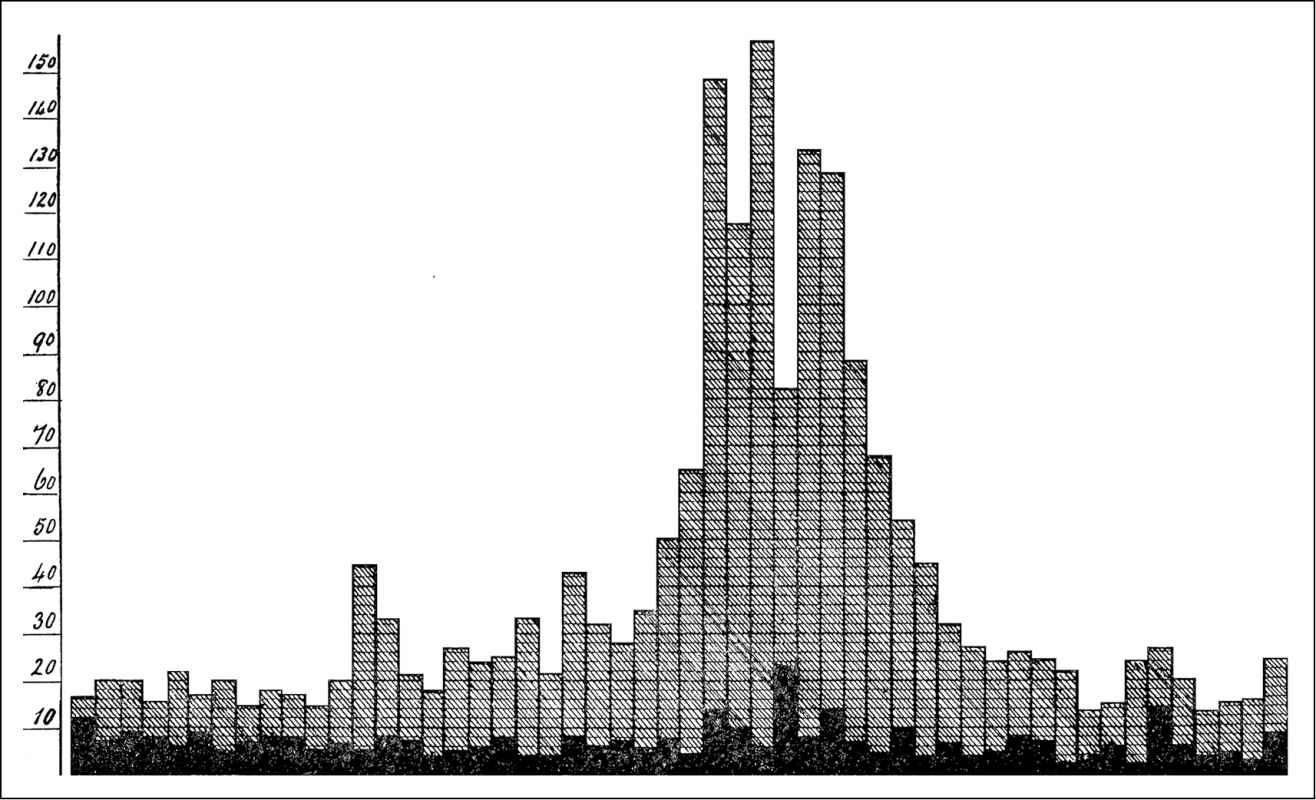

This graph depicts Parisian infants in 1903 who died of gastrointestinal disease within the first year of life, from week 1 to week 52. Breastfed infants (solid bars) were significantly less likely to die than were bottle-fed infants (hatched bars).

The problem of how to safely consume milk several hours (or days) after its collection was solved in the 1860s with a relatively simple process: heating milk for long enough to kill most of the bacteria within but not so long as to alter its sensory qualities or nutritional value. This method of food treatment, devised by Louis Pasteur, came to be known as pasteurization. The health consequences of pasteurization were immediate and immense. Those most at risk of milk-borne disease in the nineteenth century were infants, as infants fed cows milk were several times more likely to die than those fed from the breast. , however, infant mortality rates in urban centers dropped by around 20 percent.

Today, pasteurized milk is considered one of the safest foods to consume, associated with less than 1 percent of all food-borne illnesses. Oddly, however, people are increasingly opting to drink unpasteurized milk, and as a consequence, the rates of milk-borne disease are rising. Between 2007 and 2009, the United States experienced thirty outbreaks related to the bacteria Campylobacter, Salmonella, and E. colioutbreaks linked to the consumption of unpasteurized milk. buying raw, unpasteurized milk for a variety of reasons: the belief that raw milk tastes better than pasteurized milk, that raw milk has higher nutritional content than pasteurized milk (which it does not), that raw milk is what humans were intended to drink, and that consumers should have the right to choose whether their milk is pasteurized or not. Those who reject pasteurized milk in favor of a more natural alternative do so seemingly blind to the fact that, before the advent of pasteurization, thousands of people suffered organ failure, miscarriage, blindness, paralysis, and even death at the hands of milk-borne diseases.

Do people fully understand what they are rejecting when they reject pasteurizing? Probably not. Pasteurization is counterintuitive. Its counterintuitive because germs are counterintuitive. Germs are living things that cannot be seen; they are passed from one host to another without detection, and they make us ill several hours or days after we come in contact with them. Also counterintuitive is the idea that germs transform our food from sources of nutrition to sources of disease but that we can stop germs from doing so by killing them with heat. Heating food to kill germs is a widespread practice in the food industry. Several types of food are pasteurized (or otherwise heat-treated) before they hit the shelvesbeer, wine, juice, canned fruits, canned vegetablesnot just milk. It is ironic that advocates for unpasteurized milk are seemingly okay with pasteurized beer and canned peaches. Either they believe that forgoing pasteurization is a justified risk for milk but not for other foods, or, more likely, they fail to understand what pasteurization is and why it is a necessary safeguard against food-borne illness.

The science behind pasteurization is as sound as science gets, but many people reject this science. They reject not just the science behind pasteurization but science in general, from immunology to geology to genetics. A recent survey of American adults found that only 65 percent believe that humans have evolved over time, compared with 98 percent of the members of the worlds largest scientific society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). believe that climate change is due mostly to human activity, compared with 87 percent of AAAS members. And only 37 percent of American adults believe that genetically modified foods are safe to eat, compared with 88 percent of AAAS members.

to accept science than liberals, religious individuals are less likely to accept science than secular individuals, and misinformation breeds skepticism and hostility toward scientific ideas. But these factors are not the only causes of science denial. Psychologists have uncovered another: intuitive theories.

Intuitive theories are our untutored explanations for how the world works. They are our best guess as to why we observe the events we do and how we can intervene in those events to change them. Intuitive theories cover all manner of phenomenafrom gravity to geology to illness to adaptationand they operate from infancy to senescence. The problem is, they are often wrong. Our intuitive theory of illness, for instance, is grounded in behavior (what we should and should not do to stay healthy), not microbes. Thus it seems incredible that heating milk could render it safer to drink or that injecting dead viruses into our bodies, as done in vaccination, could confer immunity to live strains of the disease. Likewise, our intuitive theory of geology assumes that the earth is a static object, not a dynamic system, and thus we find it inconceivable that humans could be changing the earth itself, causing earthquakes though hydraulic fracking or global warming though carbon emission.