The Book of Disquiet

Copyright 2017 by Margaret Jull Costa

Copyright 2013 by Jernimo Pizarro

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or website review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

First published in this arrangement in Portuguese by Tinta-da-china as Livro do desassossego in 2013.

Obra publicada com o apoio do CamesInstituto da Cooperao e da Lngua I.P. (Published with the support of CamesInstituto da Cooperao e da Lngua I.P.)

Manufactured in the United States of America

First published by New Directions clothbound in 2017

Design by Erik Rieselbach

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Date to come

Names: Pessoa, Fernando, 18881935, author. | Pizarro, Jernimo, editor. | Costa, Margaret Jull, translator.

Title: The book of disquiet : the complete edition / Fernando Pessoa ; edited by Jernimo Pizarro ; translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa.

Other titles: Livro do desassossego. English

Description: First edition. | New York : New Directions Publishing Corporation, 2017. | First published in Portuguese as Livro do desassossego.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017000589 | ISBN 9780811226936 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : Pessoa, Fernando, 18881935. | Poets, Portuguese20th century Biography.

Classification: LCC PQ9261.P417 Z 46213 2017 | DDC 869.1/41 [ B ] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017000589

eISBN: 9780811226943

New Directions Books are published for James Laughlin

by New Directions Publishing Corporation

80 Eighth Avenue, New York 10011

Contents

Introduction

Fernando Pessoas life divides neatly into three periods. In a letter to the British Journal of Astrology dated 8 February 1918, he wrote that there were only two dates he remembered with absolute precision: 13 July 1893, the date of his fathers death from TB when Pessoa was only five; and 30 December 1895, the day his mother remarried, which meant that, shortly afterwards, the family moved to Durban, where his new stepfather had been appointed Portuguese Consul. In that same letter, he mentions a third date too: 20 August 1905, the day he left South Africa and returned to Lisbon for good.

That first brief period was marked by two losses: the deaths of his father and of a younger brother. And perhaps a third loss too, that of his beloved Lisbon. During the second period, despite knowing only Portuguese when he arrived in Durban, Pessoa rapidly became fluent in English and in French.

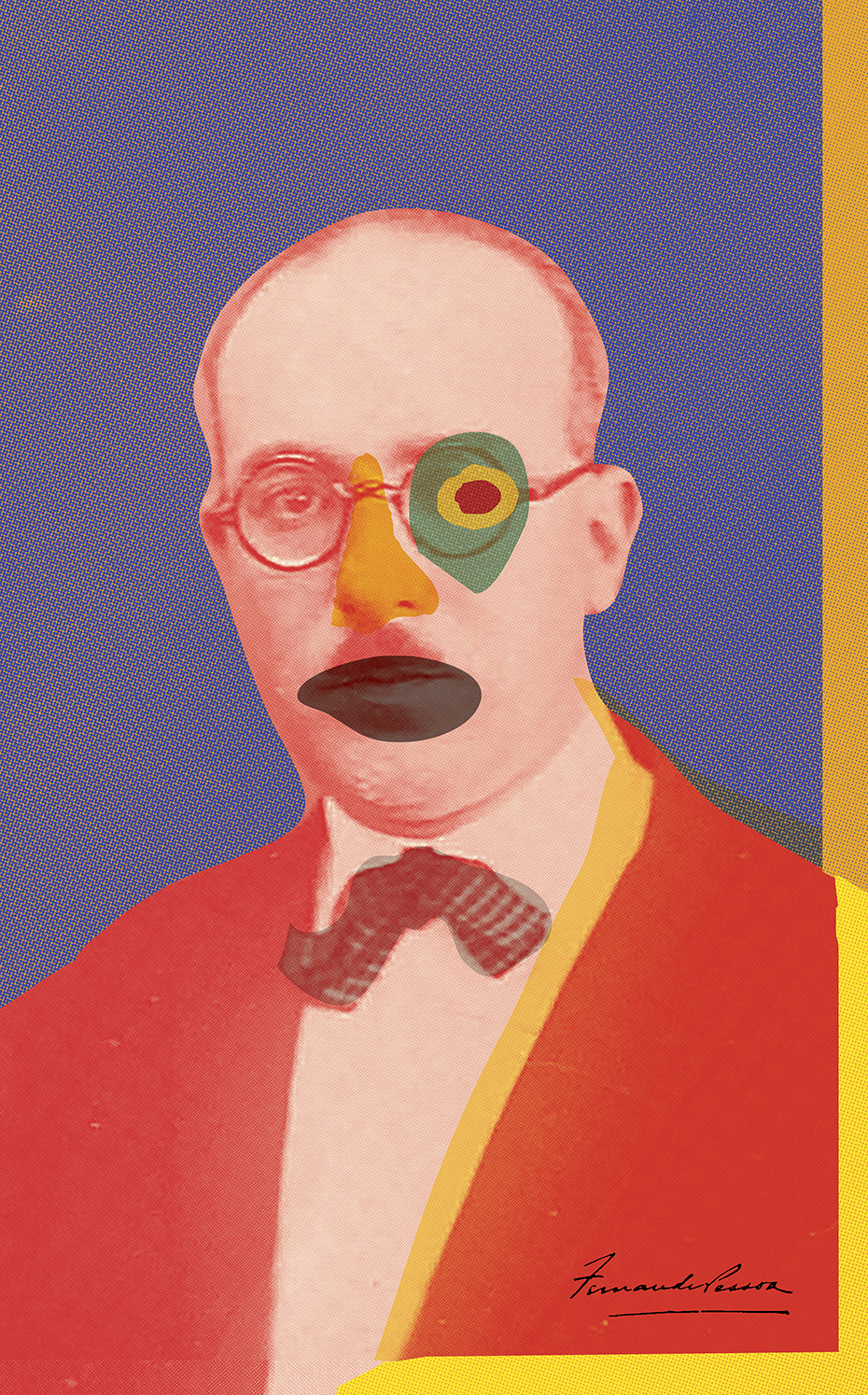

He was clearly not the average student. When asked years later, a fellow pupil described Pessoa as: A little fellow with a big head. He was brilliantly clever but quite mad. In 1902, just six years after arriving in Durban, he won first prize for an essay on the British historian Thomas Babington Macaulay. Indeed, he appeared to spend all his spare time reading or writing, and had already begun creating the fictional alter egos, or as he later described them, heteronyms, for which he is now so famous, writing stories and poems under such names as Chevalier de Pas, David Merrick, Charles Robert Anon, Horace James Faber, Alexander Search, and more. In their recent book Eu sou uma antologia (I am an anthology), Jernimo Pizarro and Patricio Ferrari list 136 heteronyms, giving biographies and examples of each heteronyms work. In 1928, Pessoa wrote of the heteronyms: They are beings with a sort-of-life-of-their-own, with feelings I do not have, and opinions I do not accept. While their writings are not mine, they do also happen to be mine.

The third period of Pessoas life began when, at the age of seventeen, he returned alone to Lisbon and never went back to South Africa. He returned ostensibly to go to university. For various reasons, though among them, ill health and a student strike he abandoned his studies in 1907 and became a regular visitor to the National Library, where he resumed his regime of voracious reading philosophy, sociology, history and, in particular, Portuguese literature. He lived initially with his aunts and, later, from 1909 onwards, in rented rooms. In 1907, his grandmother left him a small inheritance and in 1909 he used that money to buy a printing press for the publishing house, Empreza bis, which he set up a few months later. Empreza bis closed in 1910, having published not a single book. From 1912 onwards, Pessoa began contributing essays to various journals; from 1915, with the creation of the literary magazine Orpheu, which he cofounded with a group of artists and poets including Almada Negreiros and Mrio de S-Carneiro, he became part of Lisbons literary avant-garde and was involved in various ephemeral literary movements such as Intersectionism and Sensationism. Alongside his day job as freelance commercial translator between English and French, he also wrote for numerous journals and newspapers, translated Nathaniel Hawthornes The Scarlet Letter, short stories by O. Henry and poems by Edgar Allan Poe, as well as continuing to write voluminously in all genres. Very little of his own poetry or prose was published in his lifetime: just one slender volume of poems in Portuguese, Mensagem (Message), and four chapbooks of English poetry. When he died in 1935, at the age of forty-seven, he left behind the famous trunks (there are at least two) stuffed with writings nearly thirty thousand pieces of paper and only then, thanks to his friends and to the many scholars who have since spent years excavating that archive, did he come to be recognized as the prolific genius he was.

Pessoa lived to write, typing or scribbling on anything that came to hand scraps of paper, envelopes, leaflets, advertising flyers, the backs of business letters, etc. He also wrote in almost every genre poetry, prose, drama, philosophy, criticism, political theory as well as developing a deep interest in occultism, theosophy, and astrology. He drew up horoscopes not only for himself and his friends, but also for many dead writers and historical figures, among them Shakespeare, Oscar Wilde, and Robespierre, as well as for his heteronyms, a term he chose over pseudonym because it more accurately described their stylistic and intellectual independence from him, their creator, and from each other for he gave them all complex biographies and they all had their own distinctive styles and philosophies. They sometimes interacted, even criticizing or translating each others work. Some of Pessoas fictitious writers were mere sketches, some wrote in English and French, but his three main poetic heteronyms Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis, lvaro de Campos wrote only in Portuguese and each produced a very solid body of work.

Yet even this book had more than one author and was never completed, never put into any order, remaining always fragmentary. Its first author was Vicente Guedes, who wrote semi-symbolist prose pieces for inclusion in something that, as early as 1913, Pessoa was already calling The Book of Disquiet. These texts often described particular states of mind or imaginary landscapes or offered advice to would-be dreamers or even unhappily married women (a subject about which the apparently celibate Pessoa knew nothing at all at first hand) or those who, like him, had lost their religious faith. Around 1920, however, the book seemed to lose its way, and Pessoa forgot about Guedes and the