Kassia St. Clair is a freelance writer and a former assistant books and arts editor at The Economist, and writes regularly for Elle Decoration. Her popular column on color there sparked the idea for this book.

www.kassiastclair.com

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

First published in Great Britain by John Murray (Publishers), an imprint of Hodder & Stoughton Ltd.

Published by arrangement with Hodder & Stoughton Ltd.

Published in Penguin Books 2017

Copyright 2016 by Kassia St. Clair

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF C ONGRESS CATALOGING-I N-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: St. Clair, Kassia, author.

Title: The secret lives of color / Kassia St. Clair.

Description: New York : Penguin Books, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017014300 | ISBN 9780143131144 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: ColorPsychological aspectsHistory. | ColorSocial aspectsHistory. | Symbolism of colorsHistory. | BISAC: ART / History / General. | ART / Color Theory. | ART / Techniques / Color.

Classification: LCC BF789.C7 S64 2017 | DDC 155.9/1145dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017014300

Version_1

For Fallulah

The purest and most thoughtful minds are those which love color the most.

John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice (18513)

Contents

Preface

I fell in love with colors in the way most people fall in love: while concentrating on something else. Ten years ago, while researching eighteenth-century womens fashions, I would drive down to London to gaze at yellowing copies of Ackermanns Repository, one of the worlds oldest lifestyle magazines, in the Victoria and Albert Museums wood-clad archive. To me, the descriptions of the latest fashions of the 1790s were as mouthwatering and bewildering as the tasting menu of a Michelin-starred restaurant. One issue described [a] Scotch bonnet of garnet-colored satin, the ends trimmed with a gold fringe. Another recommended a gown of puce-colored satin to be worn with a Roman mantle of scarlet kerseymere. At other times, the well-dressed woman would be nothing without a pelisse in hair brown, a bonnet trimmed with coquelicot-colored feathers or lemon-colored sarcenet silk. Sometimes there were colored plates accompanying the descriptions to help me decipher what hair brown could possibly look like, but often there were not. It was like listening to a conversation in a language I only half understood. I was hooked.

That worst and vilest of all colors, pea-green!

Arbiter Elegantiarum, 1809

Years later, I had an idea that would allow me to write about my passion month in, month out, turning it into a regular magazine feature. Each issue I would take a different shade and pull it apart at the seams to discover its hidden mysteries. When was it fashionable? How and when was it made? Is it associated with a particular artist or designer or brand? What is its history? Michelle Ogundehin, the editor of the British Elle Decoration, commissioned my column and in the years since I have written about colors as ordinary as orange and as recherch as heliotrope. These columns provided the germ for this book and I am profoundly grateful.

I dont believe there are off-putting colors.

David Hockney defending another shade of greenolive, 2015

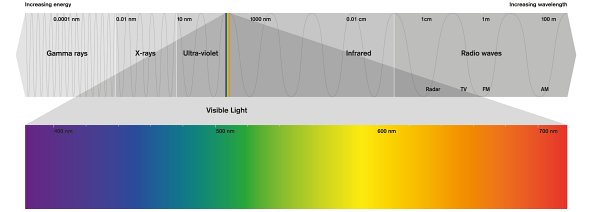

The Secret Lives of Color is not intended to be an exhaustive history. This book is broken down into broad color families and I have included someblack, brown, and whitethat are not part of the spectrum as defined by Sir Isaac Newton. color swatch) of other interesting hues along with suggestions for further reading.

To view the colors featured in this book, access http://bit.ly/2ycmYgQ on a device that displays color.

Light is therefore color, and shadow the privation of it.

J. M. W. Turner, 1818

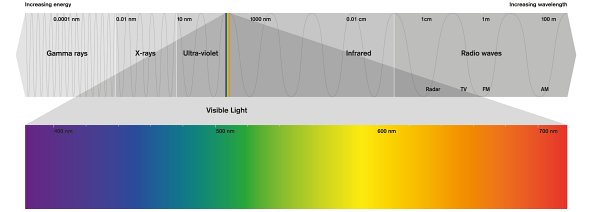

Color vision

How we see

Color is fundamental to our experience of the world around us. Think of hi-vis jackets, brand logos, and the hair, eyes, and skin of those we love. But how is it, precisely, that we see these things? What we are really seeing when we look at, say, a ripe tomato or green paint, is light being reflected off the surface of that object and into our eyes. The visible hit our eyes and are processed by our brains. So, in a way, the color we perceive an object to be is precisely the color it isnt: that is, the segment of the spectrum that is being reflected away.

When light enters our eyes it passes through the lenses and hits the retinas. These are at the backs of our eyeballs and are stuffed with light-sensitive cells, called rods and cones because of phenomenon is not completely understood, but it is usually genetic and is more prevalent in men: around 1 in 12 men are affected compared to 1 in 200 women. For people with normal color vision, when cone cells are activated by light, they relay the information through the nerve system to the brain, which in turn interprets this as color.

This sounds straightforward, but the interpretation stage is perhaps the most confounding. A metaphysical debate over whether colors really, physically exist or are only internal manifestations has raged since the seventeenth century. The squall of dismay and confusion on social media over the blue and black (or was it white and gold?) dress in 2015 shows how uncomfortable we are with the ambiguity. This particular image made us acutely aware of our brains post-processing: half of us saw one thing, the other half something completely different. This happened because our brains normally collect and apply cues about the ambient lightwhether we are in full daylight or under an LED bulb, for exampleand texture. We use these cues to adjust our perception, like applying a filter over a stage light. The poor quality and lack of visual clues like skin color in the dress image meant that our brains had to guess at the quality of the ambient light. Some intuited that the dress was being washed out by strong light and therefore their minds tuned the colors to darken them; others believed the dress to be in shadow, so their minds adjusted what they were seeing to brighten it and remove the shadowy blue cast. That is how an Internet full of people looking at the same image saw very different things.

Whiteness and all gray Colors between white and black, may be compounded of Colors, and the whiteness of the Suns Light is compounded of all the primary Colors mixd in a due Proportion.

Sir Isaac Newton, 1704

Simple arithmetic

On light

In 1666, the same year that the Great Fire of London consumed the city, a 24-year-old Isaac Newton began experimenting with prisms and beams of sunlight. He used a prism to prize apart a ray of white light to reveal its constituent wavelengths. This was not revolutionary in itselfit was something of a parlor trick that had been done many times before. Newton, however, went a step further, and in doing so changed the way we think about color forever: he used another prism to put the wavelengths back together again. Until then it had been assumed that the rainbow that pours out of a prism in the path of a beam of light was created by impurities in the glass. Pure white sunlight was considered a gift from God; it was unthinkable that it could be broken down or, worse still, created by mixing colored lights together. During the Middle Ages mixing colors at all was a taboo, believed to be against the natural order; even during Newtons lifetime, the idea that a mixture of colors could create white light was anathema.