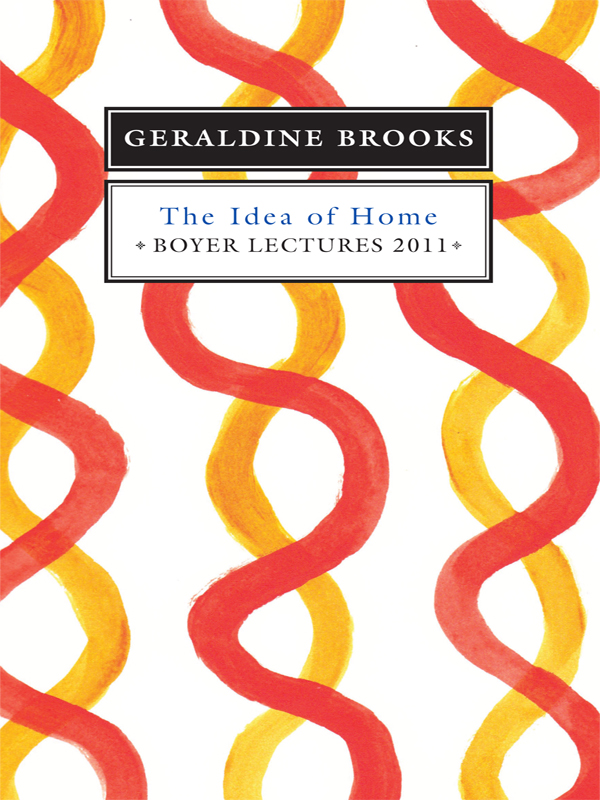

I began to write these words on the island of Marthas Vineyard, where I now live. It was a warm day in early July. Sunlight dappled the page, filtered through the leaves of an apple tree that was old before I was born.

Not far away, but unaware of me, a muskrat browsed in the grasses by the brook. Red-winged blackbirds swooped across the water and a goldfinch, like a drop of distilled sunshine, darted through the glossy branches of an ilex.

The muskrat, the birds and the holly tree are natives here. I am not. Only my dog, a liver-and-tan Kelpie, is a fellow exotic. Ten years ago, I plucked him from a paddock in New South Wales and set him down in another hemisphere. He is insouciant about this, as befits his kind. He is the quintessential Aussie canine whose legendary toughness begat the expression, Thatd kill a brown dog.

So while his warm flanks twitch in a doggie doze, it falls to me to reflect on what it means to live so far from our homeplace, so far, indeed, that the cold winds of July have been replaced by this soft and buttery summer air. I cannot explain to my Kelpie that the Indo-European root of the word home is haunt. Nor can I explain to him how and why it is that I am haunted by absence and distance, by dissonance and difference, even if the alien corn that we will eat for dinner tonight is a sweeter variety than the starchy cobs of my Aussie childhood.

Nothing is as sweet in the end as country and parents, ever,

Even if, far away, you live in a fertile place.

Odysseus said that. Or rather, Homer did. I know next to nothing about Homer who he was, how he lived yet I feel he knows my heart. Separated by 3000 years, by gender and culture and geographic space, this ancient shadow is able to put words to the feelings that I have on a sunny day on a little island, as I think of the larger island that is my native home; that sits, like Ithaca, low and away, the farthest out to sea, where the ribs of warm sandstone push up through thin, eucalyptus-scented soils.

Home. Haunt. I sit in my garden and look across to the house I have now; a house the first beams of which were cut and shaped a century before the white history of Australia even began. When I run my hand over that rough-textured oak, I imagine the hand that planed it the hand of a grist miller, himself an exotic transplant, the second or third in a line of English settlers who had come to this place drawn by the power of rushing water.

If any home is haunted, this one should be. In 1665, the very first miller, Benjamin Church, bought the land from the native people of the place, the Wampanoag. He dammed the wild brook they called the Tiasquam, and set his grindstones turning. In so doing, he destroyed the herring run that had fed the Wampanoag each spring, when the fish known as the silver of the ocean poured upstream to spawn.

Benjamin Church dammed the brook.

It is just one sentence in a long story. The story of human alteration to the natural world. It happened on the Tiasquam brook in Marthas Vineyard, as it happened in uncountable places. As it happens now, in the Amazon, in Africa, in Western Australia, Tasmania, the Alaskan Arctic and innumerable corners of the world. A choice, a change, and the planet that is our only home reels and buckles under the accumulated strain.

Often, this story has also compassed stories of dispossession, in which the needs of the newcomers and their industry disrupted the imperatives of the native people. As Benjamin Church built his mill in 1665, an English neighbour fenced pasture for his imported livestock, and the Wampanoag were no longer free to hunt the deer and waterfowl that sustained them. Another settler set his hard-hoofed beasts loose to trample the clam beds, and a band of Wampanoag went hungry that night.

War followed, as war so often has followed such acts of dispossession. In 1675, the Wampanoag on the mainland rose up against the English colonists. Benjamin Church, grist miller no longer, became a captain in the English army.

His principal foe was the Wampanoag leader, Metacom. For six months, Metacom had the English on the run, destroying a dozen settlements. The colonial enterprise in New England teetered. It was Church, the former miller, who devised a way to turn the tide of battle. He enlisted Indians at odds with Metacom to teach the English their guerrilla tactics. On a humid summer day in 1676, Church led the force that trapped Metacom and shot him dead. He regarded Metacoms dead body and declared him a doleful, great, naked, dirty beast. He ordered the corpse drawn and quartered and had the quarters hung from four trees. Church kept the head, which he sold in Plymouth, at a day of Thanksgiving, for thirty shillings. It was placed on a tall pole to overlook the feast.

Everyone knows the story of the first Plymouth Thanksgiving, in 1621. Metacoms father, Massasoit, attended that one, offering help and friendship to the hapless, half-starved English Puritans. Few know the story of the Plymouth Thanksgiving of 1676, presided over by Massasoits sons decapitated, rotting head. We like that earlier story much better. Lets not do black armband history. Pass the turkey. Lets we forget.

But I cant forget. Though Benjamin Churchs mill was torn down, this land bears his imprint. The Tiasquam brook remains dammed, the herring absent. And the grindstone is still here, set as a doorstep at the entrance to my house. Two metres in diameter, almost half a metre thick. When my foot lands on its notched ridges, words from Gerard Manley Hopkinss poem echo in my head:

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

and wears mans smudge and shares mans smell

Benjamin Churchs mill was built a hundred years before the Industrial Revolution that dismayed Hopkins. But it industrialised this landscape. And now I live where he lived, in an American home on Indian land, haunted by ghosts who lived and died unaware that my land, my homeplace, even existed.

I did not mean to become part of this story, to know, so intimately, all this history so very far removed, and yet so sadly similar, to our own. Metacom has much in common, after all, with Pemulwuy in Sydney or Yagan in Perth, guerrilla resisters whose heads also ended up on display Pemulwuys pickled in spirits and Yagans shrunken and smoked. But thats black armband history, too, and, as a schoolgirl in 1960s Sydney, I did not learn it. In those days, I could not have told you that the home I lived in stood upon Eora land, nor any details of the dispossession that occurred there. I only knew that I was happy, growing up there.