Handel

by

Romain Rolland

Copyright 2013 Read Books Ltd.

This book is copyright and may not be

reproduced or copied in any way without

the express permission of the publisher in writing

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Contents

Romain Rolland

Romain Rolland was born on 29th January 1866, in Clamecy (a small town in central France). Rolland was a French dramatist, novelist, essayist and art historian, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915. His family had both townspeople and farmers in its lineage, a fact which caused Rolland to once introspectively state that he saw himself as a representative of an antique species.

Accepted to the cole normale suprieure in 1886, he first studied philosophy, but his independence of spirit led him to abandon that so as not to submit to the dominant ideology. He received his degree in history in 1889 and spent two years in Rome, where his encounter with Malwida von Meysenbug (who had been a friend of Nietzsche and of Wagner) and his discovery of Italian masterpieces were decisive for the development of his thought. When he returned to France in 1895, he received his doctoral degree with his thesis The origins of modern lyric theatre and his doctoral dissertation, A History of Opera in Europe before Lully and Scarlatti . For the next two decades, he taught at various lyces in Paris before directing the newly established music school Ecole des Hautes Etudes Sociales from 1902-11. His first book was written in 1902, when he was thirty-six years old.

Rollands first book turned out to be his masterpiece - The Peoples Theatre advocated a popular theatre, open to the masses. It was not published until 1913, but most of its contents had appeared in the Revue dArt Dramatique between 1900 and 1903. Rolland attempted to put his theory into practice with his melodramatic dramas about the French Revolution, Danton (1900) and The Fourteenth of July (1902) - plays which were staged by some of the most influential theatre directors of the twentieth century, but it was his ideas that formed a major reference point for subsequent practitioners. Rolland indicted the bourgeoisie for its appropriation of the theatre, causing it to slide into decadence, and the deleterious effects of its ideological dominance. In proposing a suitable repertoire for his peoples theatre, Rolland rejects classical drama in the belief that it is either too difficult or too static to be of interest to the masses. Drawing on the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, he proposes instead an epic historical theatre of joy, force and intelligence which will remind the people of its revolutionary heritage and revitalize the forces working for a new society.

A demanding, yet timid young man, Rolland did not like the teaching he had to do alongside his writing. He was first and foremost an author and playwright. Assured that literature would provide him with a modest income, he resigned from the university in 1912. Rolland was also a lifelong pacifist, and was one of the few major French writers to retain his pacifist internationalist values. To avoid being conscripted in the war, he moved to Switzerland. He protested against the first World War in Au-dessus de la Mle (1915), and Above the Battle (1916). In 1924, his book on Gandhi contributed to the Indian nonviolent leaders reputation and the two men met in 1931.

Rolland later moved to Villeneuve, a town on the shores of Lake Geneva, to devote himself (once again), to writing. His most famous novel is the ten-volume Jean Christophe (1903 - 1912), which brought together his views on music, social matters and international relations all told through the character of a German musical genius. His other novels are Colas Breugnon (1919), Clrambault (1920), Pierre et Luce (1920), and Lme enchante (19221933). Despite this prolific output, Rollands life was interrupted by health problems and by his near continuous travelling. His voyage to Moscow (1935), on the invitation of Maxim Gorky, was an opportunity to meet Joseph Stalin, whom he considered the greatest man of his time.

After this successful meeting, Rolland served unofficially as ambassador of the French artists, to the Soviet Union. However, as a pacifist, he was uncomfortable with Stalins brutal repression of the opposition. He attempted to discuss his concerns with Stalin, and was involved in the campaign for the release of the Left Opposition activist/writer Victor Serge and wrote to Stalin begging clemency for Nikolai Bukharin. In 1937, he came back to live in Vzelay (a town in Burgundy, north-central France), which, in 1940, was occupied by the Germans. During the occupation, he isolated himself in complete solitude.

Never stopping his work, in 1940, Rolland finished his memoirs. He also placed the finishing touches on his musical research on the life of Ludwig van Beethoven. Shortly before his death, he wrote Pguy (1944), in which he examines religion and socialism through the context of his memories. Rolland died on 30th December, 1944, aged seventy-eight.

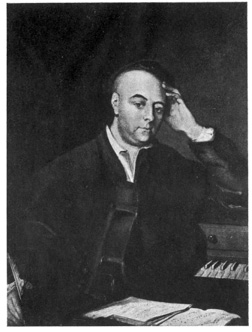

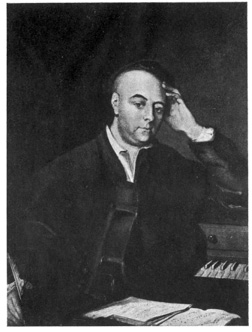

GEORGE FREDERICK HANDEL

(From a Portrait by Mercier in the possession of the Earl of Malmesbury.)

Frontispiece.]

HANDEL

BY

ROMAIN ROLLAND

TRANSLATED BY

A. EAGLEFIELD HULL

MUS. DOC. (OXON.)

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY THE EDITOR

17 MUSICAL ILLUSTRATIONS AND 4 PLATES

1916

PREFACE

For a proper appreciation of the colossal work of Handel many years of study and a book of some two hundred pages are very insufficient. To treat at all adequately of Handels life and work needs a whole lifetime in itself, and even the indefatigable and enthusiastic Chrysander, who devoted his life to this subject, has hardly encompassed the task.... I have done what I could; my faults must be excused. This little book does not pretend to be anything more than a very brief sketch of the life and technique of Handel. I hope to study his character, his work, and his times, more in detail in another volume.

ROMAIN ROLLAND.

INTRODUCTION

BY THE EDITOR

H ERE in England we are supposed to know our Handel by heart, but it is doubtful whether we do. Who can say from memory the titles of even six of his thirty-nine operas, from whence may be culled many of his choicest flowers of melody? M. Rolland rightly emphasises the importance of the operas of Handel in the long chain of musical evolution, and it seems impossible for anyone to lay down his book without having a more all-round impression than heretofore of this giant among composers.

M. Saint-Sans once compared the position of a conductor in front of the score of a Handel oratorio to that of a man who sought to settle with his family in some old mansion which has been uninhabited for centuries. The music was different altogether from that to which he was accustomed. No nuances, no bowing, frequently no indication of rate, and often merely a sketched-in bass.... Tradition only could guide him, and the English, who alone could have preserved this, he considers, have lost it.

Can it be recovered to any extent, and, if so, how?

Behind each towering figure of genius are to be found numbers of eloquent men who prepared the way for him; and amongst these precursors there is frequently discovered one who exercised a dominating influence over the young budding genius. Such an influence was exercised by Zachau on Handel, and M. Rolland rightly gives due importance to the consideration of this old masters teachings and compositions, a careful study of which should go far to supplying the right key to Handels music. One of the great shortcomings in the general musical listener is a lack of the historical view of music. It is a long cry from Bach and Handel to Debussy and Scriabin, but we shall be all the better for looking well at both ends of the long musical chain which connects the unvoiced expression of the past with the vague yet certain hopes of the future.