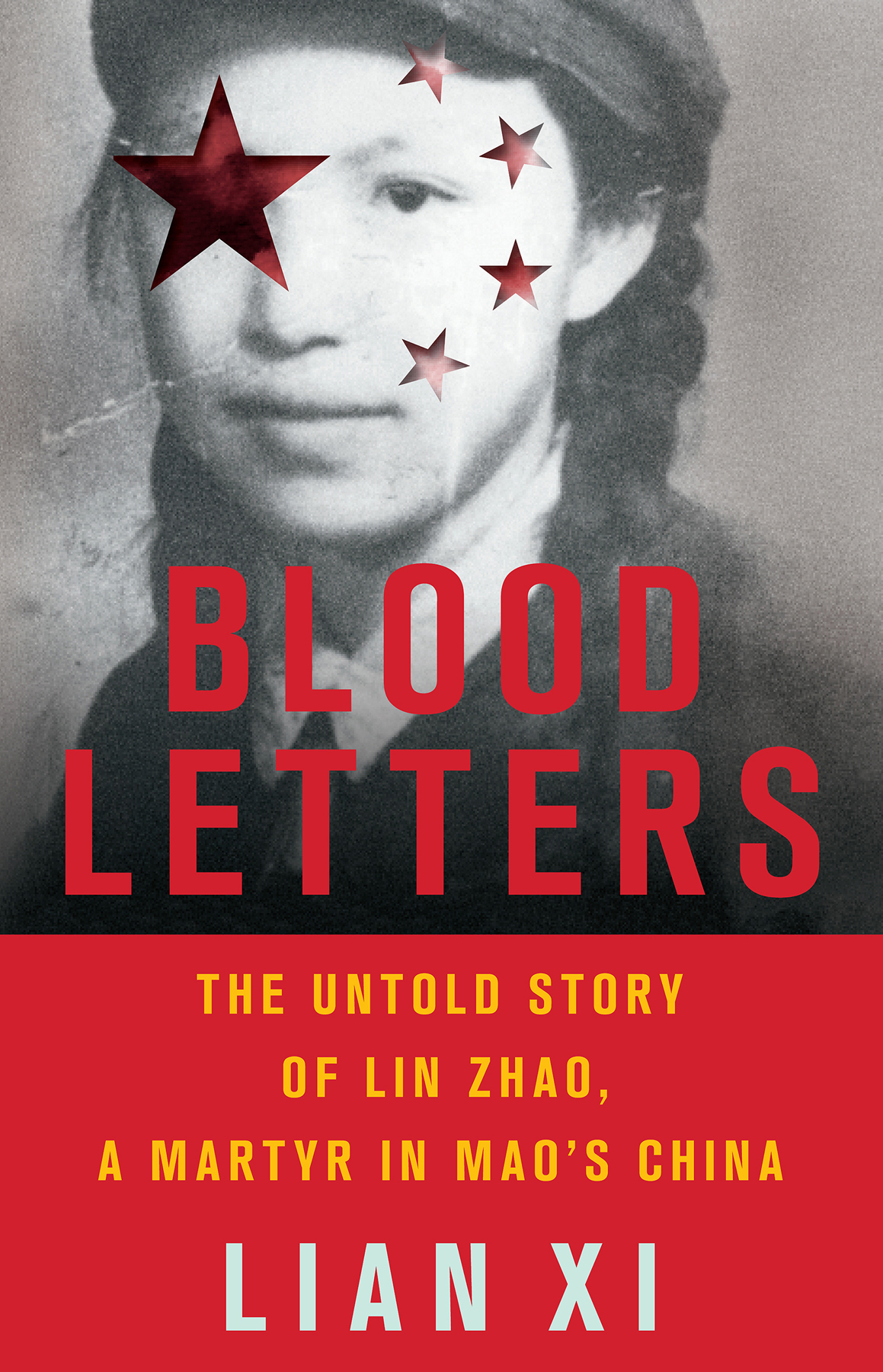

T O THOSE WHO LABORED TO PRESERVE L IN Z HAOS LEGACY AND TO KEEP HER SPIRIT ALIVE

O N M AY 31, 1965, THIRTY-THREE-YEAR-OLD L IN Z HAOPOET, JOURNALIST , dissidentwas tried in the Jingan District Peoples Court in Shanghai. She was charged as the lead member of a counterrevolutionary clique that had published A Spark of Fire, an underground journal that decried Communist misrule and Maos Great Leap Forward, which caused an unprecedented famine in 19591961 and claimed at least thirty-six million lives nationwide.

Lin Zhao had also contributed a long poem entitled A Day in Prometheuss Passion to the journal. It mocked Mao as a villainous Zeus trying, and failing, to force Prometheus to put out the fire of freedom taken from heaven. According to the authorities, the poem viciously attacked the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the socialist system and inspired fellow counterrevolutionaries to blatantly call for a peaceful, democratic, and free China. She was sentenced to twenty years in prison.

This is a shameful ruling! Lin Zhao wrote on the back of the verdict the next day, in her own blood. But I heard it with pride! It is the enemys estimation of my individual act of combat. Deep inside my heart I feel the pride of a combatant! I have done too little. It is far from enough. Yes, I must do more to live up to your

It was an unexpected, jarring note in the symphony of Maos revolution. The Communist movement, which began in the 1920s and which Mao had led since the 1930s, had triumphed with the founding of the Peoples Republic in 1949. The revolution had turned communism into a sacred creed and a mass religion in China, complete with its Marxist and Maoist scriptures, priests (the cadres), and revolutionary liturgy.

The cult of Mao dated to the 1940s but blossomed with the publication of Quotations from Chairman Maoknown in the West as The Little Red Bookin 1964. Over one billion copies were printed over the next decade. During the Cultural Revolution, launched in 1966, collective rituals of slogan chanting and of waving The Little Red Book were performed daily in front of the portrait of the great leader. Meanwhile, some 4.8 billion Mao badges were made. The largest was as big as a soccer ball.

Sacrilege was hard to imagine and rare. Even those condemned counterrevolutionaries sent to execution grounds had often chanted Long live Chairman Mao as shots were fired, in a last-ditch effort to escape the wrath of the revolution and to attest their loyalty to it.

At a time when critics of the party had been silenced throughout China, Lin Zhao chose to oppose it openly from her prison cell. From the day of my arrest I have declared in front of those Communists my identity as a resister, she wrote in a blood letter to her mother from prison. I have been open in my basic stand as a freedom fighter against communism and against tyranny.

Lin Zhaos dissent seemed as futile as it was suicidal. What sustained it was her intense religious faith. She had been baptized in her teens at the Laura Haygood Memorial School, a Southern Methodist mission school in her hometown of Suzhou, but drifted away from the church when she joined the Communist revolution in 1949 to help emancipate the masses and create a new, just society, as she Thereafter she gradually returned to a fervent Christian faith.

As a Christian, she believed that her struggle was both political and spiritual. In a postsentencing letter from prison to the editors of Peoples Dailythe partys mouthpieceshe explained that, in opposing communism, she was following the line of a servant of God, the political line of Christ. My life belongs to God, she claimed. God willing, she would be able to live. But if God wants me to become a willing martyr, I will only be grateful from the bottom of my heart for the honor He bestows on me!

Lin Zhaos defiance of the regime was unparalleled in Maos China. The tens of millions who perished as the direct result of the CCP rule died as victims, their voices unheard. No significant, secular opposition to the ideology of communism was recorded in China during Maos reign. Lin Zhao endured as a resister because of her democratic ideals and because her Christian faith enabled her to preserve her moral autonomy as well as political judgment, which the Communist state had denied its citizens. Her faith provided a counterweight to the religion of Maoism and sustained her in her dissent.

T HE TITLE OF this book comes from Lin Zhaos impassioned means of expressing that dissent. During her imprisonment, an official document read, Lin Zhao poked her flesh countless times and used her filthy blood to write hundreds of thousands of words of extremely reactionary, extremely malicious letters, notes, and diaries, madly attacking, abusing, and slandering our party and its leader. Her letters were addressed variously to the party propaganda apparatus, the United Nations, the prison authorities, and her mother. She called them her freedom writings.