Copyright 2017 by Noah Strycker

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-544-55814-4

Cover design by Martha Kennedy

Image () Sorendls/Getty Images

e ISBN 978-0-544-55815-1

v1.0917

Foreword

Birds are real. If I had to justify extreme birding, that would be my first defense. Even as we dash around in a mad quest for the biggest list of bird sightings, were keenly attuned to realitynot just the birds but also geography, weather patterns, forest types, tide schedules, and myriad other factors, because everything in nature is connected. Other people may take up hobbies to escape reality, but birding has the opposite draw. Its a deep dive into the real world.

A year is also a real thingone orbit around the sunand yearlong birding efforts are the epitome of extreme birding. The first Big Years were done in the 1890s by Lynds Jones and W. L. Dawson in Lorain County, Ohio, cooperating and competing to run up their county tallies. By the 1930s, a few birders were competing for the biggest annual list for all of North America north of Mexico. The popularity of the pursuit has been creeping up ever since, and so have the totals produced. Recent North American Big Year champs have pushed the theoretical maximum and cratered their bank accounts by flying back and forth across the continent, chasing every rarity that strayed within our boundaries.

I myself did a Big Year as a teenager in the 1970s, on a very modest budget, but the restriction of boundaries rankled. I took time out for three trips into Mexico that year, even though birds south of the border wouldnt count. The allure of tropical diversity was irresistible. Even then, the wide world of variety beckoned more than the idea of birding within borders.

Peter Alden, a pioneer leader of international birding tours, had ticked more than 2,000 species globally during 1968. We all thought that was cool, but in that era, no one seriously thought about topping that score. World birding was hard. Thousands of tropical bird species had never been illustrated at all, and good field guides existed only for North America, Europe, and South Africa. Bird-finding publications were almost unheard-of outside the United States. Birding tours still took in relatively few destinations. For my friends and me, an overseas birding trip involved weeks of preparation, and often more research afterward to figure out what wed seen. As rewarding as these trips were, no one wanted to cram too many into a single year.

In the few decades since that time, world birding has gone through two major revolutions, utterly changing the game.

The first big change, gradual but massive, has been the information explosion. Today, every known bird species has been superbly illustrated. Practically anywhere on Earth, we can choose among multiple bird ID guides. Thousands of mystery birds are now less mysterious, their secrets revealed. Excellent sound recordings make all the difference in finding elusive targets, especially in dense tropical haunts. At one time, if you wanted to see a Zigzag Heron, for example, you wandered in the Amazon Basin for a year and prayed for a miracle. Now that its voice and precise habitats are known, this weird little wader isnt hard to find.

An even bigger change is the emergence of a worldwide community. Not long ago birding was a lopsided pursuit, popular in a few English-speaking countries, plus northern Europe and Japan. Between these silos of activity, communication was limited. The rise of the Internet changed that. Listservs brought about instant communication among the continents. Social media like Facebook even broke the language barrier with the sharing of bird photos and automated translation. At the same time, local birding communities have sprung up in most nations. In the past, if you wanted advice on birding Colombia, you sought out North Americans or Europeans who had been there. Today that country has a thriving birding scene, and Colombian experts know their own avifauna better than any outsider. Knowledge is now decentralized. And since birders everywhere tend to be open and sharing, travelers now have vastly more potential sources of help.

For birding the world, the biggest driver of change is eBird, the massive online database of bird sightings. Launched in 2002, eBird was limited to North America at first, going global in 2010. Its acceptance and growth worldwide have been phenomenal, and it utterly changes how we perceive the potential in distant lands. Once, when reading about Blyths Hawk-Eagle in the Malay Peninsula and Indonesia, it would have seemed impossibly remote. Now a few clicks into eBird will display half a dozen sites where the species has been seen within the last month, and we can check how consistent it is at those sites and who the local observers are. Its no exaggeration to say that eBird has become the global hub for active birders.

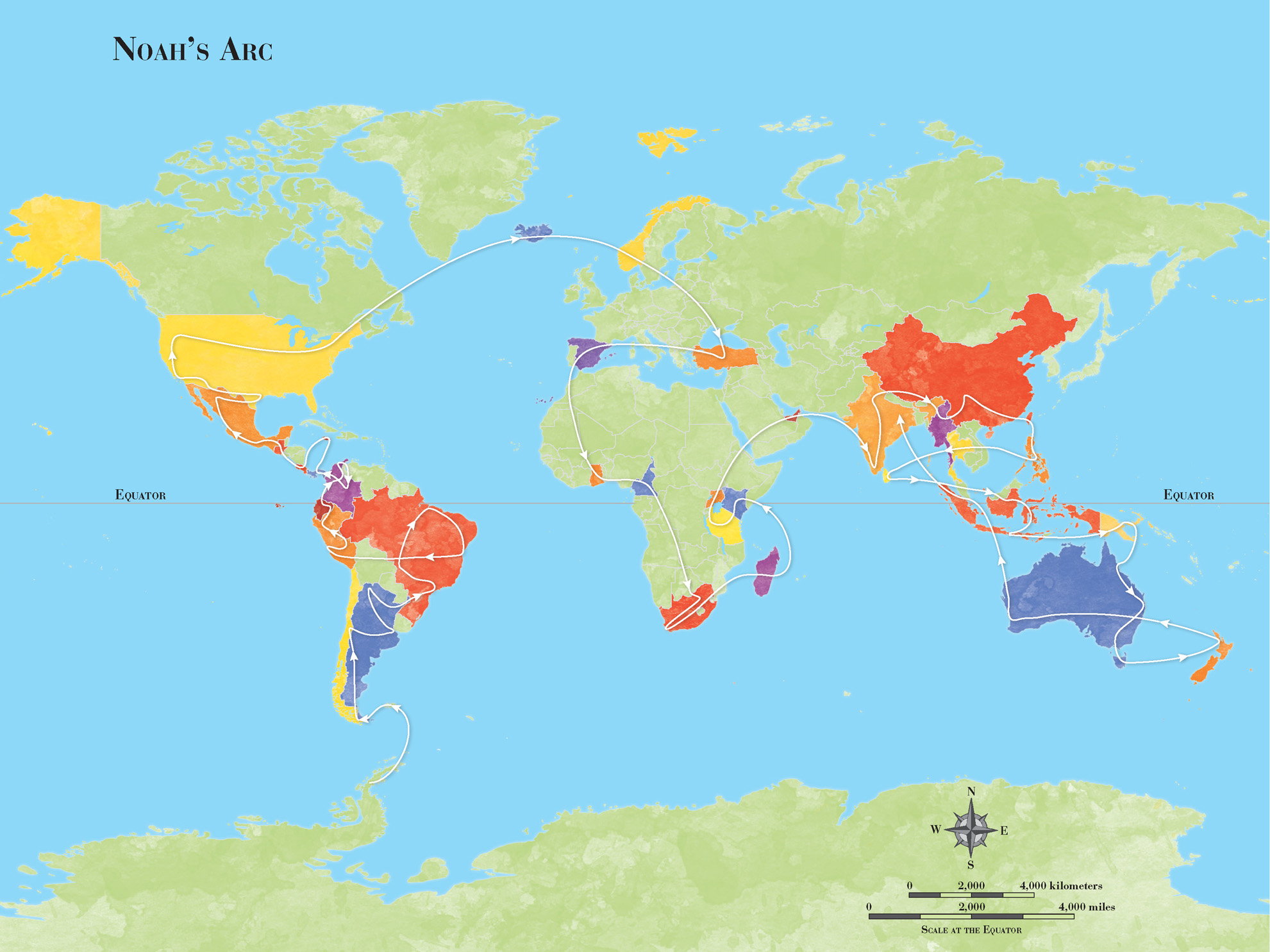

As world birding has evolved, the global year list record has pushed upward. The American ornithologist James Clements ran up a total over 3,600 in 1989just before the Internet became a factor. An intrepid British couple, Alan Davies and Ruth Miller, surpassed 4,300 species in 2008just before eBird went global. The time was ripe for someone to push past 5,000, recording more than half the worlds birds in a single year. The previous champsAlden, Clements, Davies, and Millerhave all been friends of mine, and I watched with keen interest to see who would be next.

We could not have hoped for a better contender than Noah Strycker. This brilliant young man was already a veteran of detailed field research, already renowned for writing about birds with depth and grace; no one could dismiss him as just a lister. In one carefully planned, continuous sprint around the globe, he shattered previous records. He also made a point of going native and connecting with local experts everywhere. The result is a thoughtful, vivid portrait of the worlds birds and birders.

At this moment in history, its easier than ever to see birds worldwide... and all over the planet, birds face unprecedented perils. A pessimist might say were in the sweet spot between accessibility and extinction. I dont see it that way. Noah Strycker turned up plenty of birds on his grand tour, but more important, he met people in every land who care passionately about those birds and who will fight for their survival. Everything in nature is connected, and as the birders of the world become more connected also, the reality of the future looks brighter already.

Kenn Kaufman

March 2017

1

End of the World

O N NEW YEARS DAY, superstitious birdwatchers like to say, the very first bird you see is an omen for the future. This is a twist on the traditional Chinese zodiacwhich assigns each year to an animal, like the Year of the Dragon, or Ratand its amazingly reliable. One year, I woke up on January 1, glanced outside, and saw a Black-capped Chickadee, a nice, friendly creature that everybody likes. That was a fantastic year. The next New Year, my first bird was a European Starling, a despised North American invader that poops on parked cars and habitually kills baby bluebirds just because it can. Compared to the Year of the Chickadee, the Year of the Starling was pretty much a write-off.

Next page