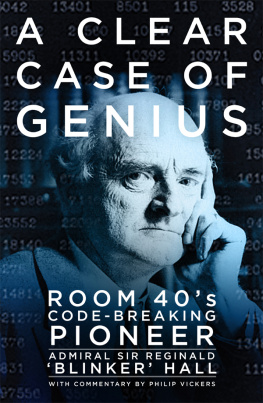

A CLEAR

CASE OF

GENIUS

The phrase a clear case of genius is taken from a letter of 17 March 1918 from the American Ambassador in London, Dr Walter Hines Page, to President Woodrow Wilson.

To my parents, Frances Alice and Reginald Henry Vickers, who survived two world wars and introduced me to Jules Vernes The Mysterious Document, The Cryptogram and Mathias Sandorf, which first generated my interest in secret intelligence.

O voyagers, O seamen,

You who came to port, and you whose bodies

Will suffer the trial and judgement of the sea,

Or whatever event, this is your real destination []

Not fare well,

But fare forward, voyagers.

T.S. Eliot, The Dry Salvages, Four Quartets

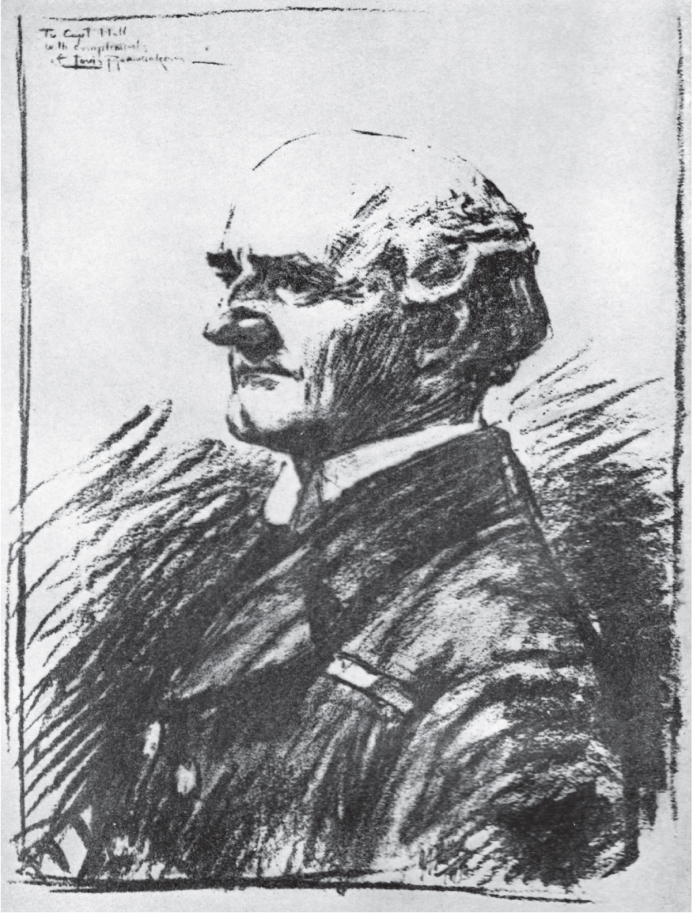

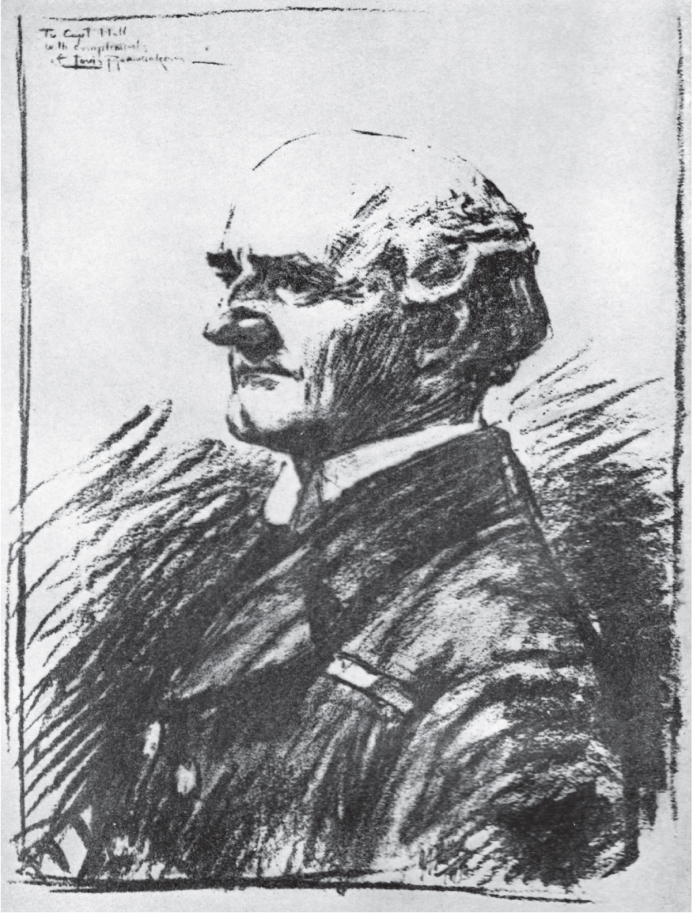

Frontispiece: Admiral Sir Reginald Hall. (Sketch by Louis Raemaker/T. Stubbs, CAC)

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

Autobiography Reginald Hall, 2017

Commentary and supporting text Philip Vickers, 2017

The right of Reginald Hall and Philip Vickers to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8510 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

I n a past intelligence world apparently populated almost exclusively by colourful and engaging characters, Blinker Hall cut a remarkable figure as an innovator, administrator and politician. He is rightly credited with having supervised some of the most successful clandestine operations of the First World War and, most importantly, of creating and nurturing Britains first dedicated cryptographic organisation. His name is immediately associated with the code-breakers of Room 40, the development of the cryptanalytical techniques which cracked the German Foreign Ministrys diplomatic cypher, and with the foundation of a highly specialised branch of covert warfare.

Much has been written about Hall, in part because of what his division of the Admiralty accomplished on his watch, but when in his retirement he entered politics few outsiders knew very much at all about what his very unnaval collection of eccentric academics, playwrights, actors and novelists had achieved equipped with just paper and pencil. The full background of, for example, the decryption of the Zimmermann Telegram, or the interception of the Kaisermarines cypher system, would not be disclosed for years in the anticipation that such measures could be required in a future conflict. Understandably, successive British governments sought to impose discretion on the cognoscenti, but that effort was doomed when litigation initiated in the United States, far outside Whitehalls jurisdictional reach, threatened to reveal the scale of Britains investment in eavesdropping.

So many years later, following revelations about the impact of Bletchley Park on the Allies successful prosecution of the Second World War, and even more recent indiscretions about the role of its successor organisation, Government Communications Headquarters, Halls role acquires a special status among the pantheon of British Intelligence. Now, at last, we can get an insight into what he thought about some of the historic events to which he was witness.

Nigel West

2017

INTRODUCTION

O ne distinctive figure stands centre stage in any line-up of Intelligence Chiefs, a man with eyes that blinked rapidly. He was Admiral Sir Reginald Blinker Hall, Director of Naval Intelligence (DNI) throughout the First World War and chief of Room 40, his headquarters in the Admiralty.

Room 40 has been credited by many as being the most successful intelligence operation of all time, and as Winston Churchill observed of Halls worldwide network in The World Crisis, There were others a brilliant confederacy whose names even now are better wrapt in mystery. This comment was true when written in 1923, and remains so today. Several biographies of Hall, and many histories of British secret intelligence agencies, have brought his name before the general public, yet he remains an enigmatic figure. This should not surprise us on two counts.

First, it is in the nature of secret services that much more remains hidden than is available to the wider public. Second, Halls autobiography was banned by order of the government and was mostly destroyed. Only seven draft chapters out of the thirty he contemplated and partly completed survive; and they represent a proportion of the opus he began work on in 1926, but was forced to abandon when the Admiralty intervened in August 1933 and ensured the destruction of Chapters 4, 817 and 1924. Chapter 18 is virtually a duplicate of Chapter 7, and of the missing material we know only that two of them, one of which was Chapter 20, were concerned with Naval Intelligence Division (NID) activities in the western Mediterranean.

Numerous writers have quoted from his extant chapters but it is only now, some eighty years later, that they can be published in full, with some editorial support. What emerges is a fascinating, candid account of clandestine operations that throws some light on why the autobiography came to be banned, ostensibly on security grounds. The surviving manuscript offers a unique insight into the man himself and of the work of Room 40. It highlights strengths and weaknesses and demonstrates that although times may change, the fundamental principles of intelligence collection remain relevant to todays challenges.

Hall presents a particular picture of the First World War era, and tells us much about the ninety-three extraordinary and colourful characters who inhabited, and were involved with, his organisation which routinely handled issues of maritime trade, economics, contraband and, of course, cryptography and covert operations. Many of his subordinates who are today quite unknown or forgotten were, at the time, crucial performers in the secret war. These and other individuals have been researched by the editor so as to begin to answer such important questions as: who is Colyn; what part does the mysterious Graves play; what role did the Deutschland play; and why is Colonel Cockerill so important?

Hall wrote his autobiography in collaboration with Ralph Straus, the erudite author, particularly noted for his remarkable book The Unspeakable Curll. Hall was in very good hands here and, once the ban was imposed, Straus suggested to Hall that the book should be rewritten in the form of a novel. Hall rejected this idea but, had it gone ahead, we would know a great deal more. According to Halls grandson, Timothy Stubbs, when Straus died a great number of the Admirals papers were destroyed. There is also evidence that Hall himself destroyed much of Room 40s papers at the time of its closure in 1919.

Next page