Contents

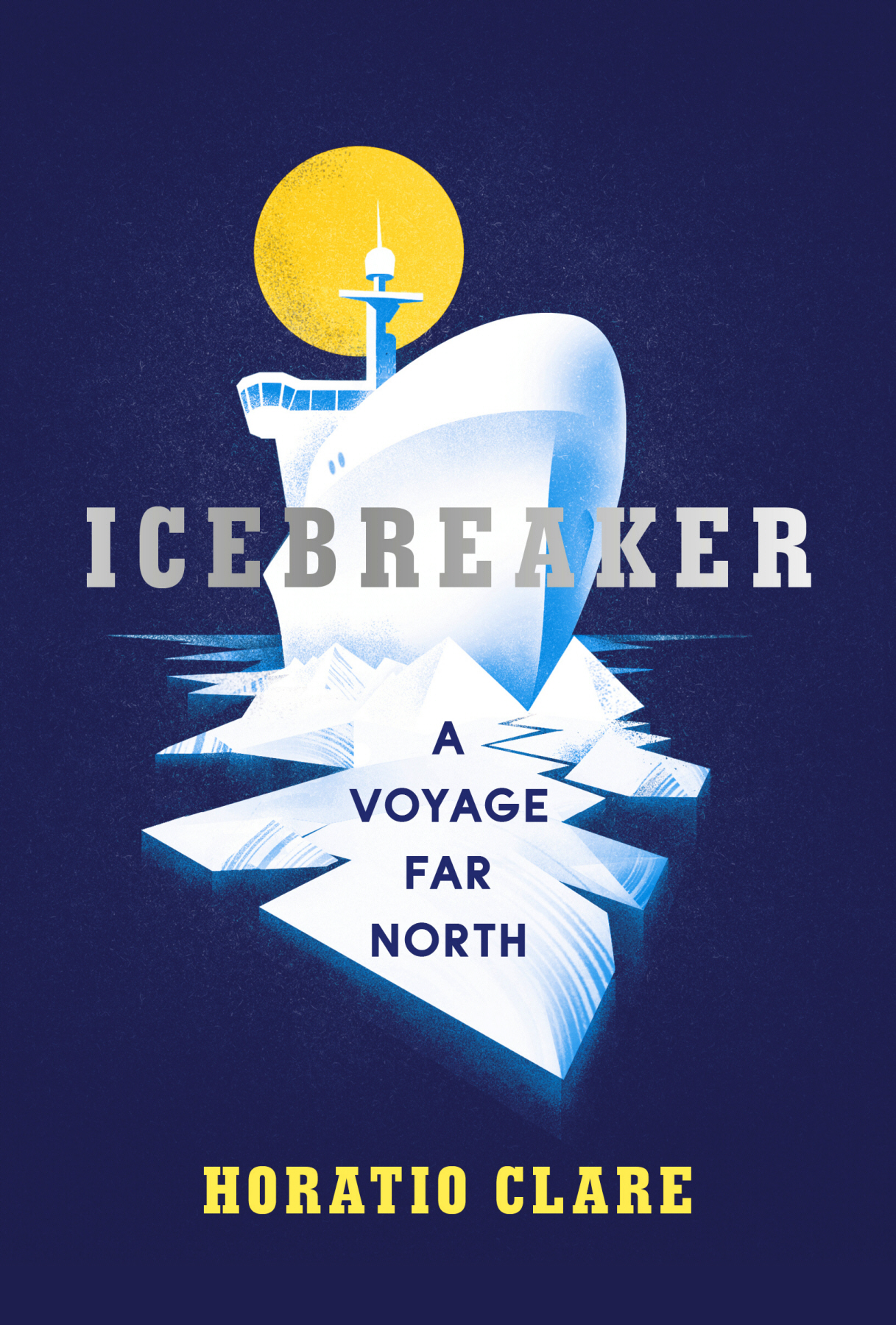

About the Book

We are celebrating a hundred years since independence this year: how would you like to travel on a government icebreaker?

A message from the Finnish embassy launches Horatio Clare on a voyage around an extraordinary country and an unearthly place, the frozen Bay of Bothnia, just short of the Arctic circle. Travelling with the crew of Icebreaker Otso, Horatio, whose last adventure saw him embedded on Maersk container vessels for the bestseller Down to the Sea in Ships, discovers stories of Finland, of her mariners and of ice.

Finland is an enigmatic place, famous for its educational miracle, healthcare and gender equality as well as Nokia, Angry Birds, saunas, questionable cuisine and deep taciturnity. Aboard Otso Horatio gets to know the men who make up her crew, and explores Finlands history and character. Surrounded by the extraordinary colours and conditions of a frozen sea, he also comes to understand something of the complexity and fragile beauty of ice, a near-miraculous substance which cools the planet, gives the stars their twinkle and which may hold all our futures in its crystals.

About the Author

Horatio Clare is the bestselling author of the memoirs Running for the Hills and Truant and the travel books A Single Swallow (which follows the birds migration from South Africa to the UK), Down to the Sea in Ships (the story of two voyages on container vessels) and Orison for a Curlew, a journey in search of one of the worlds rarest birds. His books for children include Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot and Aubrey and the Terrible Ladybirds. Horatios essays and reviews appear on BBC radio and in the Financial Times, the Observer and the Spectator, among other publications. He lives with his family in West Yorkshire.

ALSO BY HORATIO CLARE

Non-fiction

Running for the Hills

Truant: Notes from the Slippery Slope

Sicily: Through Writers Eyes

A Single Swallow

Down to the Sea in Ships

Orison for a Curlew

Myths and Legends of the Brecon Beacons

Fiction

The Princes Pen

For Children

Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot

Aubrey and the Terrible Ladybirds

To my shipmates,

at home and afloat,

with love and thanks.

And through the drifts the snowy clifts

Did send a dismal sheen:

Nor shapes of men nor beasts we ken

The ice was all between.

S.T. Coleridge,

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

CHAPTER 1

Ghosts

LIKE A SMALL luminous yeti in search of food I tramp towards the centre of Oulu. Snow floods out of the darkness, shoaling around the lights, settling deep on the town. Nothing else moves. It is half past eleven on a Sunday night and I am quietly, dizzily happy. Tomorrow morning my ship comes in. In my violently orange coat, warm as a bears belly, I am ready for the ice. The ice is close by. You can smell it, a hard purity in the cold.

The north seems a vast imagined surround, pine-dark, duned with snow and specked with Arctic towns as deserted as Oulu, their garrisons all stood down. They are in bed all over Ostrobothnia now. They are in bed across the water in Sweden and over the border in Russia. Seven hundred miles south-west, beyond the Skagerrak, the Danes must have finished their Sunday hygge (to stay in with loved ones and enjoy an absence of stress); around here, perhaps, the odd Finn is still practising kalsariknnit (to get drunk at home alone in your underwear with no intention of doing anything else). In the peace I experience one of those leaps of the heart, of love and thrill for the world, a euphoric gratitude for life and travel for which there can be no one word in any tongue.

Oulu is at the northern end of Finlands west coast on the shore of the Bay of Bothnia. The Bay is the northern armpit of the Gulf of Bothnia, which is the northern arm of the Baltic sea between Finland and Sweden. We are a hundred frozen miles short of the Arctic Circle. I am here to join Icebreaker Otso, the bear. Otso is coming in to change her crew and take on food and fuel. Tomorrow we go to sea. For ten days I am going to break ice with a crew of Finnish seafarers, mostly in darkness, certainly in snow.

For months I have been waiting for tomorrow, since the message came from Pekka, whom I knew a little at school. He was an angular, amused boy then, with that staccato way of speaking English the Finns have which lends itself to wryness. Last year he wrote to me, I just got an idea which might interest you, given your fascination with ships. Would you like to hear more?

Pekka is press counsellor at the Embassy of Finland in London. He is charged with raising his countrys profile in 2017, the centenary of the nations birth.

Would you like to travel on a government icebreaker? I think if you do the journey, something will come of it.

A Finnish proverb says, The brave eat the soup, the timid die of hunger. I have no great appetite for public relations trips but I did not hesitate: darkness, ice, Finland and a ship! Three days ago I turned up in London lugging a bag stuffed with thermals and layers and merino and a hat and an under-hat, mittens and under-gloves, these thumping army surplus boots and this ridiculous coat, to find I was thirty-six hours early for the flight.

Another Finnish proverb says, Dont jump before you reach the ditch. A man comes back from beyond the sea, but not from under the sod, says yet another. The first part of this last one is reassuring but the second is nonsense. I am also here because of a man under the sod who keeps coming back.

Pekka and I had someone in common: Thomas, an arresting boy who became a beloved man. Thomas was extremely tall; his thoughts and comments were terribly quick and his face was a satyrs, wickedly clever, the nose slightly lopsided, the impression a beautiful hotchpotch of narrowing eyes, high bones and round rumbustious jaw. Thomas could be an explosion of noise, ludic dash and charisma, or Thomas could be utterly attentive, searching your face as he listened to you, devoted to understanding what you were really trying to say. Thomas loved to solve problems. In his thirties he seemed to have cracked the problem of life. He lived in Switzerland with his family. He was engaged on a project which involved putting capital to work for charity: he was one of those people who habitually improve strangers lives simply because they can. And then, one foggy day, Thomas fell on ice while skiing. He was in a coma for weeks.

Here is the strange thing. While Thomas lay between life and death my partner gave birth to our son, and as the baby began to be able to focus on the world, as its lines and depths began to cohere, and as Thomas slipped further away, I began to see in the babys eyes, beyond all sense but there, and growing and focusing there, some blaze-bright light of will and life which I knew, which I had seen before in Thomas.

The turbulence of grief for my friend and my adoration of the child surely conjured this vision, a projection, but that is not how I experienced it. It was as though they were passing each other, brushing by each other, making some exchange in that region before and after understanding which is neither quite life nor death.