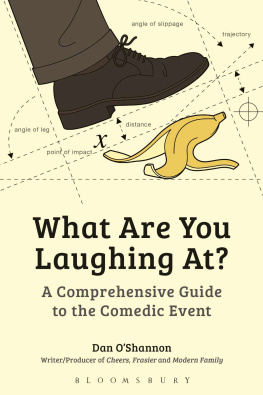

WHAT ARE YOU

LAUGHING AT?

A comprehensive guide to the

comedic event

DAN OSHANNON

CONTENTS

If youre looking for a book that will teach you how to write comedy, I suggest you keep moving. You still have time to pick up a copy of Writing Big Yucks for Big Bucks before the store closes. However, if you want to understand the bigger picturewhat is comedy, why do we respond to it in the way we dothen youve come to the right place.

* * *

Ive always been what you might call a comedy detective. I observe and create comedy and I study the laugh. Thats the true mission of the comedy detective: understand the laugh. Whats really going on? What invisible factors are shaping the response?

The answers havent always come easily. In one instance a single laugh became a 15-year riddle.

I heard it on March 12, 1977. I was barely 15 years old, living in rural Ohio. It was a Saturday night, and like most of America, my family was watching The Mary Tyler Moore Show. The episode, called Lou Dates Mary, chronicles an awkward date between Mary Richards and her boss, Lou Grant. The show builds to a moment on Marys couch, where the two characters slowly go in for a kissonly to start laughing as they realize how silly it is for them to try to turn their relationship into something its not.

The climactic moment felt slightly off to me. But it wasnt the scene. The actors were brilliant and the situation was genuinely funny. It was the studio audience. The laugh started out loud and full, but there was an odd quick taper to it. The moment left me hanging somehow.

I didnt think about it again until years later, when I was writing and producing Cheers. (Coincidentally, one of the writers on the staff was David Lloyd, who wrote many episodes of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, including Lou Dates Mary.) We were filming an episode in which the less-than-ambitious Norm does a joke where he starts to talk about taking his career and marriage seriously, but hes only kidding and cant even complete the sentence without cracking himself up. At this I heard a familiar response from the studio audience: a shriek of laughter followed by a too-quick taper. And suddenly I had the answer. I now understood the laugh Id heard 15 years earlier.

(The explanation is in Chapter 4, p. 58.)

* * *

The first step toward understanding the laugh is to understand what comedy is and how it works. Unfortunately, theres one tiny problem:

Nobody agrees on what comedy is or how it works.

For centuries, theorists have argued over comedys unifying link. Incongruity, superiority, aggression, surprise, and relief keep popping up, either singly or in combinations. Ive seen the amateur expert analyze the linguistic structure of a few jokes and extrapolate their conclusions to account for all of comedy. The true amateurs, meanwhile, divide comedy into various forms (satire, farce, insult humor, wordplay, gross-out humor, etc.) and proceed from there, not knowing that theyve already lost the battle.

And so we come to the purpose of this book: the creation of a new and comprehensive model of comedy; a model upon which any joke or humorous incident (along with the reaction it gets) can be examined effectively.

This model will allow for any variation in comedys arsenal; linguistic jokes as well as slapstick, intentional comedy along with unintentional. It accounts for the decay of old jokes, the nature of practical jokes, and the existence of meta-comedy. It will also catalog the variables of transmission that are so crucial to comedy response.

Ill be presenting new ideas in this book, as well as rearranging some old ones. By the end, youll have a true understanding of what happens when man meets comedy. Youll see how every comedic experience is unique, and youll understand the possible factors that go into every laugh.

Think of it as The Comedy Detectives Handbook.

Who am I and why should you listen to me?

Before plunging into a book of this size, you may want to know why you should trust me. Fair enough.

For me, the road began in 1970. I was sitting on a gymnasium floor with the rest of my class for a school assembly. There was a man on stage and he was making us laugh. I have no idea what he was doing; in fact, I have no recollection of the day at all except for the moment when the man paused. He was waiting for us to catch our collective breath, and he leaned against the microphone stand and mused, Theres nothing like the feeling of making people laugh.

The click inside of me was deafening. I remember looking around the room to see if anyone else had heard what I heard; or rather, connected with it like I did. Amazingly, the remark had passed over them. But they were changed, because in that moment I saw them as people, but maybe they could also be audience. I was eight years old, and Id found my calling.

I was going to be funny.

Thus began the loneliest period of my life. I was full of enthusiasm but didnt have the slightest clue how to be funny. I just knew what made me laugh. Back then it was Jerry Lewis, so I became Jerry Lewis. I learned quickly and painfully that there is also nothing like the feeling of not making people laugh. I was too young to understand the enormous difference between a character doing comedy in the context of a made-up movie and someone enacting the same behavior in real life.

In my teens I was studying sitcoms on TV, recognizing joke patterns. I analyzed cartoons. In the library I found and devoured James Thurber and Robert Benchley, trying hard to duplicate their styles in my writing. The problem? I had no perspective, no point of view. I was simply too young to generate credible material. And lets remember: my audience was mostly other kidsnot exactly the kindest crowd.

Unencumbered by popularity, I began to discover books about comedy. The first one I ever read was Steve Allens The Funny Men, written in 1956. A revelation. Around this time Leonard Maltin was writing about cartoons, comedy teams, The Little Rascals everything I watched on TV that no one wanted to discuss with me on any real critical level. I read books by Joe Adamson, George Burns, Milt Josefsberg, Walter Kerr, everything I could lay my hands on.

At age 19 I started doing stand-up comedy with original material. And I found out that indeed, there is nothing like the feeling of making people laugh.

This book is the result of what I learned over the next 30 years.

(Are you still reading this in a bookstore? Are you trying to decide between this book and Being Funny for Money by that guy who wrote for My Little Margie? Did you flip ahead and see all the diagrams I have?)

Youll notice that theres almost no citing of other comedy research in these pages. The contents are based on my observations, first as a stand-up comic and then as a sitcom writer and producer. Fortunately, I was able to work on some of the best shows in television: Newhart, Cheers, Frasier, Modern Family, and many more. I worked alongside brilliant writers, actors, and directors, and I kept my eyes and ears open the whole time.

Ive written thousands of jokes and attended thousands of rehearsals. Ive taken part in endless rewrites, all in the service of making scripts funnier. The stage has been my laboratory, and Ive witnessed the reactions of hundreds of thousands of people to joke after joke after joke, every variation imaginable. I learned that we can use jokes to trigger every feeling in the psyche. It got to the point where I could hear when the laugh was off; I could hear when we got the right response but for the wrong reason. I learned the language of laughter, not by reading about it in a book, but by immersion. I lived there.