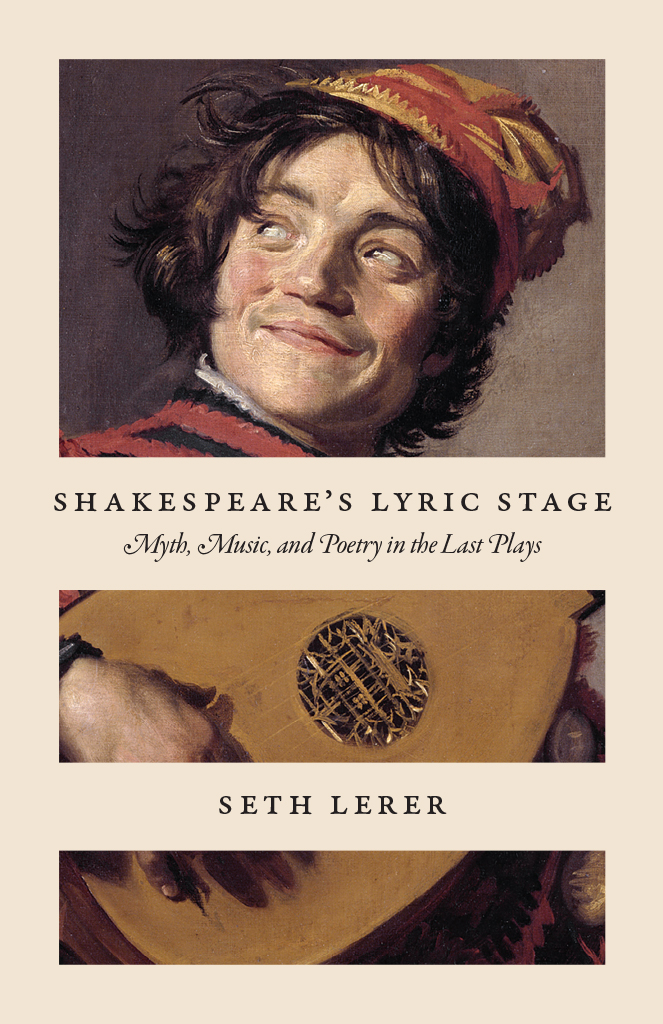

Shakespeares Lyric Stage

Shakespeares Lyric Stage

Myth, Music, and Poetry in the Last Plays

SETH LERER

The University of Chicago Press

CHICAGO & LONDON

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2018 by The University of Chicago.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 East 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-58240-5 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-58254-2 (paper)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-58268-9 (e-book)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226582689.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lerer, Seth, 1955 author.

Title: Shakespeares lyric stage : myth, music, and poetry in the last plays / Seth Lerer.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018003418 | ISBN 9780226582405 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226582542 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226582689 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH : Shakespeare, William, 15641616Technique. | Shakespeare, William, 15641616Criticism and interpretation. | English drama17th CenturyHistory and criticism. | Dramatic monologuesHistory17th century. | Music and literatureEnglandHistory17th century.

Classification: LCC PR 2995 . L 47 2018 | DDC 822.3/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018003418

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Shakespeares late plays, wrote Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1808, are a different genus, diverse in kind, not merely different in degreeromantic dramas, or dramatic romances.

Whatever scholars think, the plays continue to allure their audiences. Their complex female roles, their adventurous metaphors, and their inspirations for experimental dramaturgy speak, anew, to our early twenty-first-century sensibilities.

We may reflect and meditate along with Shakespeare, but I will argue that the ends of those activitiesfor us and for the characters within his fictionslie in an awareness of the powerlessness of the literary craft. Shakespeares late plays dramatize how poetry tries to resist patronage, how the machinations of the stage reveal the machinery behind illusion, and how increasingly improbable plots and resolutions test the faith and patience of an audience or reader. The plays may, again in Lynes words, excite wonder and reason, but they also baffle, irritate, and stun.

My book is a study of how drama turns to lyric art when faced with loss of purpose, pedigree, or power. Shakespeares late plays explore the place of the aesthetic in the exercise of rule. They raise questions about the role of poetry and music in evoking an emotional response, and they dramatize that emotional response within the fiction of the stage performance. Moreover, in the performance of such scenes of lyric ravishment or musical attention, they illustrate the challenge of staging intimacythat is, representing private moments before an audience.

These are the major features of the late plays that distinguish them from earlier works that may be full of song or magic. Midsummer Nights Dream, for example, interrogates the place of artistic performance in the maintenance of political control (whether that control is human or fairy). It shows us a commissioned spirit charged with stage-managing desire. But this is a world of fantasy: of fairy king and queen, of ancient Athenian lovers, of local rustics displaced into ravishment or lunacy. In The Tempest, there is magic on Prosperos island, but it is the magic worked by an all-too-human exiled duke. There are spirits and monsters, but we never see them fully manumitted from their master. There is ravishment of sound and sweet airs, but the poetry of this sublime dramatic moment is given neither to a human being nor to a spirit, but to Caliban. At such a moment, the central questions of my book emerge: what does it mean to have an emotional response to verbal and sonic art? What does it mean to give voice to that inner feeling before others? What happens when the audience for that voice is undeserving or unqualified to hear it?

Sing and disperse my troubles, Queen Katherine commands in Henry VIII, if thou canst. This is the challenge of late Shakespeare: the challenge to perform and have effect, the challenge to move character and audience, fictional figures and historical groups. Metamorphic music... for a victim of history. In the ten years leading up to Henry VIII, viewers would have lived through a Queen lost and a King found, a violent plot foiled, a plague come and gone, witches hunted, reason haunted, ships launched and not returned, and the first Prince of Wales in over sixty years suddenly dead. In some sense, all members of Shakespeares audience were victims of history.

Much has been made of history in Shakespeare. But little has been said about the place of history in the making of the lyric genre and its contribution to the social function of poetry in narrative drama. Most critics, even after decades of historicist hegemony, strip history from lyric poetry, affirming it a formal practice better served by close rather than contextual reading. But when it is a matter of Shakespeare, formalism may not suffice. Do his verses truly remain freestanding objects of our delectation, guiding our understanding wholly through internal form and figure? Or are they counters in a currency of social and political exchange, whose shards of meaning must be recovered? Helen Vendler continues to aver that any respectable account of a poem ought to have considered closely its chief formal features, and she prefaces her book about the Sonnets with this manifesto:

Because the lyric is intended to be voiceable by anyone reading it, in its normative form it deliberately strips away most social specification (age, regional location, sex, class). A social reading is better directed at a novel or a play; the abstraction desired by the writer of, and the willing reader of, normative lyric frustrates the mind that wants social fictions or biographical revelations.

What Vendler says about lyric poetry in general, I hold to be what Shakespeares late plays are about, both dramatically and historically. They ask what happens when words voiceable by anyone become uniquely voiced by characters. What happens when an old familiar poem gels in the drama of a social reading? To read or hear the lyric performances within these plays is precisely to watch characters as performers and audiencesto see the fictions of their minds frustrated, torn between a powerful response to lyric beauty and the need for restitution.

In The Tempests Ariel, in Autolycus of The Winters Tale, in Wolsey and Katherine of Henry VIII, in Cloten of Cymbeline, and in the various characters of Pericles and The Two Noble Kinsmen, Shakespeare dramatizes these tensions between the social and the aesthetic. These last plays bring together myth and music, past and present, poetry and politics, into a new lyrical history. Much of that history depends on new modes of performance and patronage emerging in the years around 1610. These include the return of the great lutenist John Dowland to James Is court and the dissemination of his music in printed form; the coalescing of royal masquery around the affirmations of the Jacobean family; and a new self-consciousness about the social and the mythic status of the poet, drawn from changing ways of reading Ovid and Chaucer in the first years of the seventeenth century. Out of these worlds emerges a distinctive understanding of the metamorphic nature of the lyric and, in turn, of the character (in all senses of that word) behind the recitation, writing down, and reading of poetry.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).