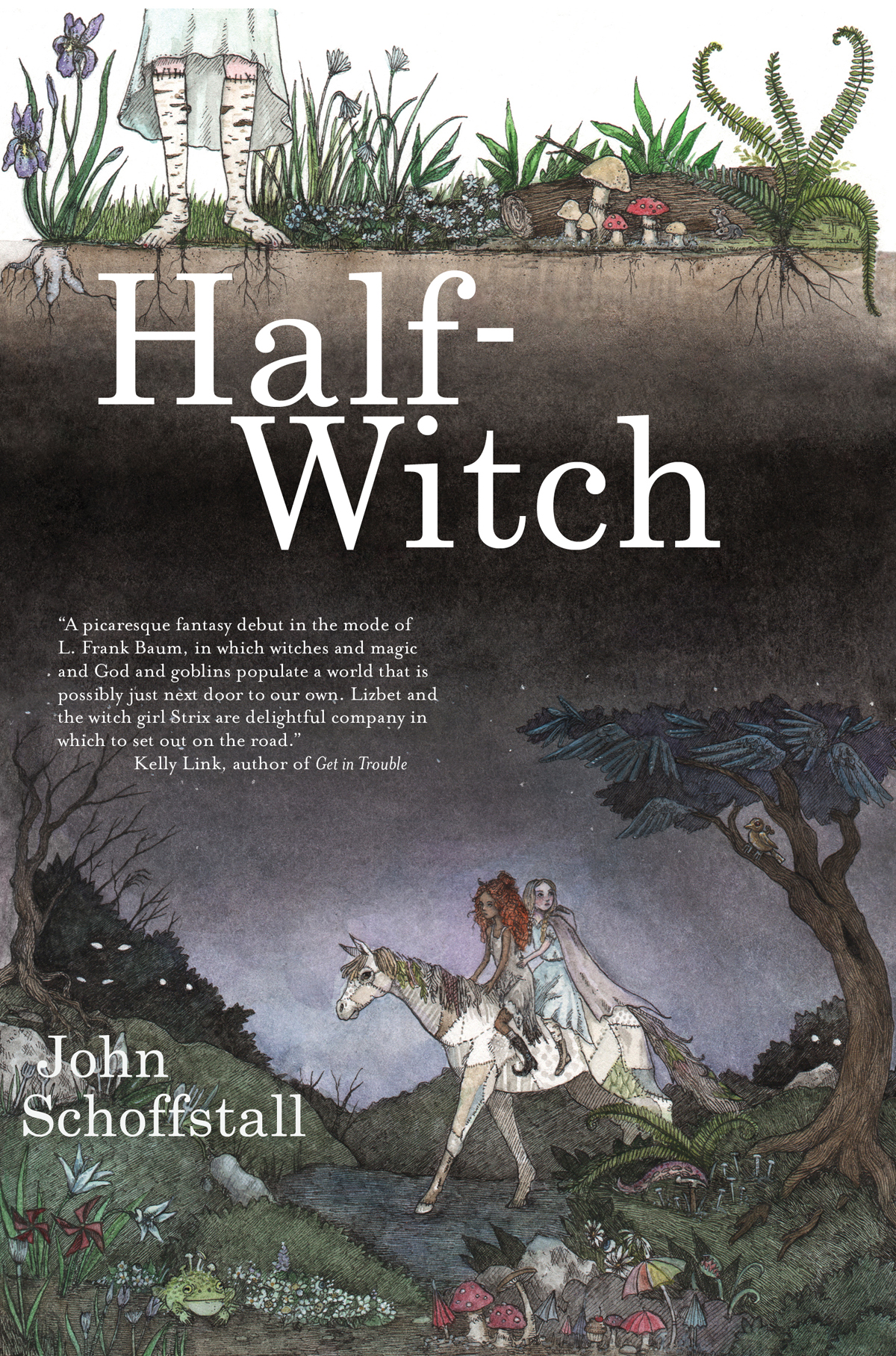

Half-Witch

a novel

John Schoffstall

This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed in this book are either fictitious or used fictitiously.

Half-Witch copyright 2018 by John Schoffstall (johnschoffstall.com). All rights reserved.

Cover illustration Half-Witch 2018 by kAt Philbin (katphilbin.com). All rights reserved.

Author photo 2018 by Sam Interrante (saminterrante.com). All rights reserved.

Big Mouth House

150 Pleasant Street #306

Easthampton, MA 01027

info@smallbeerpress.com

smallbeerpress.com

weightlessbooks.com

Distributed to the trade by Consortium.

First Big Mouth House Printing

July 2018

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Schoffstall, John, 1952- author.

Title: Half-witch : a novel / John Schoffstall.

Description: Easthampton, MA : Big Mouth House, [2018] | Summary:

Fourteen-year-old Lizbet and witch girl Strix embark upon a perilous quest

where the fates of Lizbets father and Heaven are at stake.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017047748 (print) | LCCN 2018007742 (ebook) | ISBN

9781618731418 | ISBN 9781618731401 (alk. paper)

Subjects: | CYAC: Magic--Fiction. | Witches--Fiction. | Heaven--Fiction. |

Fantasy.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.S33653 (ebook) | LCC PZ7.1.S33653 Hal 2018 (print)

| DDC [Fic]--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017047748

Text set in Minion.

Paper edition printed on 50# 30% PCR recycled Natures Natural paper in the USA.

For Jayne

Who held my head above water until we got to land

Chapter 1

My swords a rose,

My pens my nose,

My belts a snake,

My combs a rake,

My voice a bell,

My heaven, hell,

A crow my king,

My kiss a sting,

My day is night,

My love is spite!

A rhyme of Strix

When Lizbet Lenz was eight years old, she and her father, Gerhard, fled their home in Frucy-sur-St. Jacques.

Why do we have to leave? Lizbet asked. Why do they hate us?

Unforeseen accidents, Gerhard explained sadly. Misfortune. Mistrust.

Clinging to the back of Gerhards horse, they rode for their lives. An angry mob chased them. Lizbet, riding behind Gerhard and gripping his coat in her fists, risked a glimpse backward. Among the crowd she saw Marguerite and Huguette. Marguerite and Huguette were Lizbets best friends in the world. She had shared everything with them. She had confided in them all the secrets that she could never, ever tell anyone else. They had all promised to be friends forever.

Marguerite and Huguette ran in the mob beside their brothers and parents, shouting curses at Lizbet and Gerhard.

Burning tears blurred Lizbets eyes. I hate friends, she thought. I hate them. Ill never have a friend again. I promise.

After Frucy, Lizbet and Gerhard settled in Souvilliers. Lizbet broke her promise, and made friends with a girl named Rosemonde. But after a few months she and Gerhard had to flee again. Lizbets heart broke in a different way: this time she was the betrayer, unable to say good-bye to Rosemonde, unable to make good on any of her promises to her.

Why do we have to go away again? she cried to Gerhard. Why?

Misunderstandings, Gerhard told her, sighing. Unreasonable expectations. Good intentions gone awry.

And so they traveled to Yblitz, where they lived for more than a year. Until one night, when men in clanking armor pounded on the door of their fine house, yelling that they had a warrant for Gerhards arrest. Gerhard and Lizbet had to slip out through the scullery entrance and make off on a horse that Gerhard said was a friends, but Lizbet was pretty sure they were stealing.

Bad luck, Gerhard explained, shaking his head and clucking his tongue. Misadventures. Poor timing.

They fled to Zwandt. From Zwandt to Pforzenhausen. To Zoltwice. To Padz. Lizbet learned her lesson. She stopped having friends. Having friends just meant enduring the pain of losing them, again and again. Her only friends were her dolls, her father, and her God, to whom Lizbet prayed that Gerhard might someday prosper, and that she might live in one town all her life, like a normal girl.

God was always friendly and sounded sympathetic, but He just didnt get what being a normal girl meant. He liked to ramble on about about fasting. Or martyrdom. Had Lizbet ever considered becoming an anchoress, He asked?

A what?

An anchoress, God explained, was someone who let herself be walled up in a cubbyhole in some church for her entire life, with nothing to do but pray all day long. It was like solitary confinement, except that you hadnt done anything to deserve it.

It was the absolute opposite of being a normal girl.

Each time Lizbet and her father made their home in a new town, it wasnt long before they had to flee again. Each time Gerhard had a new excuse. Every year Lizbet grew more lonely.

The year Lizbet was fourteen years old, they settled in Abalia, in the farthest east of the Holy Roman Empire, beneath the snow-capped peaks of the Montagnes du Monde, the highest mountains in the world. No one knew what lay beyond the Montagnes.

This surely must be the edge of the world, Lizbet thought. We have to stay here. We have to, because theres nowhere further to go.

But one day, after they had lived in Abalia for almost a year, disaster struck.

At some point during Lizbets afternoon classes, it began to rain mice.

The mice may have started falling during the last half of Realms Despoiled on Account of the Uterine Fury or the first part of Economic Geography of the Saracen Kingdoms. While Dame Mother Pallidums nasal voice enumerated the principal rivers of the Caliphate of Andalusia, Lizbet noticed that Bruno, in the seat just ahead of hers, was staring out the window with unusual intensity. Hed better pay attention to Pally soon , Lizbet thought, or Pallys Rod of Chastening will get busy.

Brigitte, two seats over and a row ahead, also had her head turned to the window. And Robin in front of her.

The Dame Mothers voice stuttered to a halt. She turned her gaze to the window and stared.

Things were falling past the window, larger than snowflakes, and darker, and it was too warm for snow in April, anyway. One falling object landed on the sill, put its forelegs up against the glass, and wiggled its pink nose.

A mouse.

Another came behind it, and another, and another, until the sill outside the window was piled high with mice, black, white, fawn and dappled, wiggling their tails and their curious noses, tumbling over each other, falling off the sill to the ground. Teacher and class watched in silence.

Lizbet climbed onto her chair and stood on tiptoe to see out the window. She was a thin, pale girl on whom adults always felt they had to urge second helpings at the supper table. Her hair was straight and square cut, her features narrow and precise. In her black school gown and white pinafore, dark hair and pale face, she resembled a handful of ebony and ivory keys fashioned for some celestial piano, but omitted by an absentminded angel.

One by one, every student in the room turned their gaze from the mice to Lizbet, standing alone on her chair. Lizbet ignored them. In her fourteen years, she had lived in a dozen cities in five nations. Lizbet was always the stranger, always the foreigner. Because no one made things easy for her, she had learned boldness beyond her years: she went where she liked, demanded her due, and was not afraid to elbow her way to the front of a crowd. In her secret heart, loneliness tugged at her, and love for her neer-do-well father, and piety to God. But in standing up to the world of suspicious strangers into which life had dropped her, Lizbet was a lion in petticoats.