Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my dear Boss, Michael di Capua, who published my first verse, then encouraged me to try prose, and stuck with me for more than fifty years as muse and editor

BY KATHERINE APPLEGATE

E very now and then, if the fates are kindly disposed, you will come across a book and know, as certainly as you know your own soul, that it was written just for you.

I have a few such cherished books on my office bookshelf. And one of thema signed first edition, no lessjust happens to be a picture book by the inimitable Natalie Zane Babbitt.

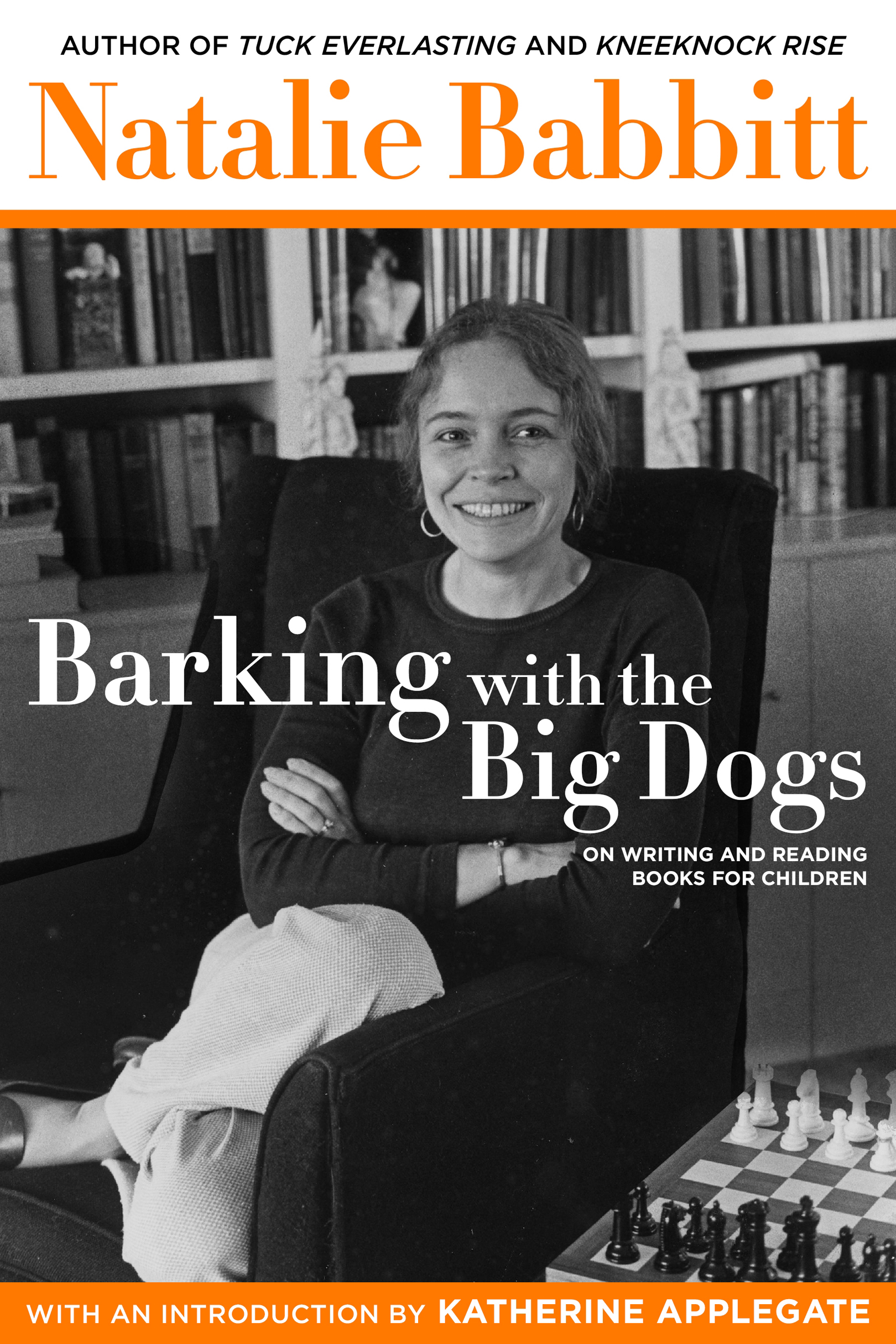

During her remarkable career, Natalie Babbitt gave us many opportunities to fall under the spell of her storytelling magic, including Kneeknock Rise, for which she was awarded a Newbery Honor, and her beloved modern classic, Tuck Everlasting .

But for me, it is one of her picture books Nellie: A Cat on Her Own that will always be first in my heart.

I was in my thirties when I came across the title, which by then had already been released in paperback. Id been trying to educate myself about childrens books, secretly wondering if I might be able to write one someday, secretly doubting I could ever pull it off.

In the books charming cover illustration, Nellie, a wooden cat marionette, sits in a straw hat bedecked with pink ribbon, staringcontentedly, it would seeminto the distance. The interior art is equally beguiling. (A lifelong pet owner, Babbitts drawings of dogs and cats practically bound off the page, their expressions every bit as nuanced as those of her humans.)

But while the art is gorgeous, its the story that snared me. Nellies life is tidily secure until the clever old woman who created her dies. How will the little toy survive, let alone dance, without someones help? With the encouragement of a real cat named Big Tom, Nellie learns to face her fears and embrace her independence. By the end of the tale, we see her dancing joyfully in the moonlight, reveling in her fine view of the wide, wild world.

Its a lovely fantasy, delicately told. But, as with all Natalie Babbitts work, its more, so much more, than that. In a mere handful of pages, this slender book challenges its readers to wrestle with big questions. How do we define independence? What does it mean to belong to yourself? How do we confront our darkest fears in order to claim the light as our own?

When I went on to read Tuck Everlasting , there they were again: big questions, this time the most ancient and profound of all. Why must we die? Would it be better to be immortal? How do we press on with our lives, knowing that eventually, as Winnie Foster says, we all just go out, like the flame of a candle?

To be honest, Nellie and Tuck left me vaguely melancholy for a while. It hurt a little to read them. They glittered too brightly with truth. And yet they were undeniably, at their hearts, resolutely hopeful stories.

When I read this fascinating collection of Babbitts speeches and essays, it came as no surprise, then, that the importance of truth-telling in childrens literature is a thematic touchstone. In all these pieces, Natalie Babbitt is unfailingly generous with her own truths as well; we learn a great deal about her fears, her loves, her work, her hopes. At the same time, were also treated to an intriguing insiders view of childrens literature as it evolved over four decades after she began publishing in 1966.

We read about an era when literature for teens (not yet dubbed Young Adult) was still in its embryonic phase. We nod in resigned agreement as Babbitt grumbles about the advent of email. We applaud as she decries the way pleasurable childhood reading has given way to assigned drudge work.

And we laugh. A lot.

How I wish Id had the pleasure of meeting Natalie Babbitt in person! The Michigander in me loves the no-nonsense, down-to-earth midwesterners voice that animates her prose. (Although she moved dozens of times, her family roots were in Ohio.) Her humor is abundant, dry, and delightful. She is self-deprecating, especially about her vocation: Were rather a motley crew, we makers of stories and pictures. (Shes got that right.) And I loved this: The world looks at us in a puzzled way and wonders, Why devote your life to writing for a group that has no money, no experience, and cant spell rhinoceros ? Such writing cant be serious.

Babbitt can be tough on childrens books, at least the sloppy, Pepto-Bismol pink variety, but only because she knows children deserve the absolute best literature we can give them. She adores teachers and librarians, the true and unsung heroes, she believes, of childrens literature. But it is children themselves for whom she reserves her deepest love and respect. And because she respects her young readers, she knows their books can be hopeful without being condescending. Her stories, like all the best fantasies, are optimistic at their core. She doesnt deny the dark. She simply reaffirms the light.

Facing the unfaceable, she calls it. Perhaps thats one of her greatest gifts to us: Natalie Babbitt is not afraid to write about being afraid. In fact, she concludes that Nellie: A Cat on Her Own my beloved picture bookis at its essence a mini-autobiography about her own fears. (An epiphany that came with a nudge from her psychologist son.) Babbitt claims she was a somewhat timid child who grew into a risk-averse adult, a homebody at heart. She protests that she is not and never could be a true pathfinder, an intrepid Winnie, the kind of person who walks into the woods in search of adventure, or an adventurous Nellie, happily dancing alone while bathed in moonshine and magic.

But of course Natalie Babbitt was a pathfinder. She took huge and daring risks with her writing. Like Maurice Sendak and E. B. White, she led children toward the dark places where other writers were afraid to venture. And with every marvelous fantasy, every good story, well told, she taught young readers how to name their fears, and thus become the heroes of their own stories.

It wasnt my idea, Babbitt writes in her preface about creating this collection, but we are grateful indeed it exists. And while we enjoy her wise words, shes no doubt ensconced in the heavenly library she describes in one of her speeches, the place where Lewis Carroll and J. M. Barrie and E. B. White and Beatrix Potter and Arnold Lobel and Arthur Rackham and Margot Zemach and all the others who have added so much to our lives meet every morning for milk and cookies and have a good time talking shop.

What excellent company she must be! For the rest of us, this brilliant book, with her fine view of the wide, wild world, is the next best thing.

There is in Rhode Island a woman who knows her way around an aphorism. She has created some wonders, from one of which the title for this collection of essays and speeches is taken. Her name is Julie Springwater, and the complete aphorism, which she gave me permission to adapt and use, says: It came from barking with the big dogs. I have been drawn to, and bemused by, this one since I first saw it printed on a handsome little magnet. The big dogs has come at last to mean, for me professionally, the people who are out there in the adult field, writers who mostly have the real clout in the author-critic-analyst business. They are the ones in the forefront, the ones who seem to have the most to say (or bark), can say (or bark) it the loudest, and are saying (or barking) it most often.