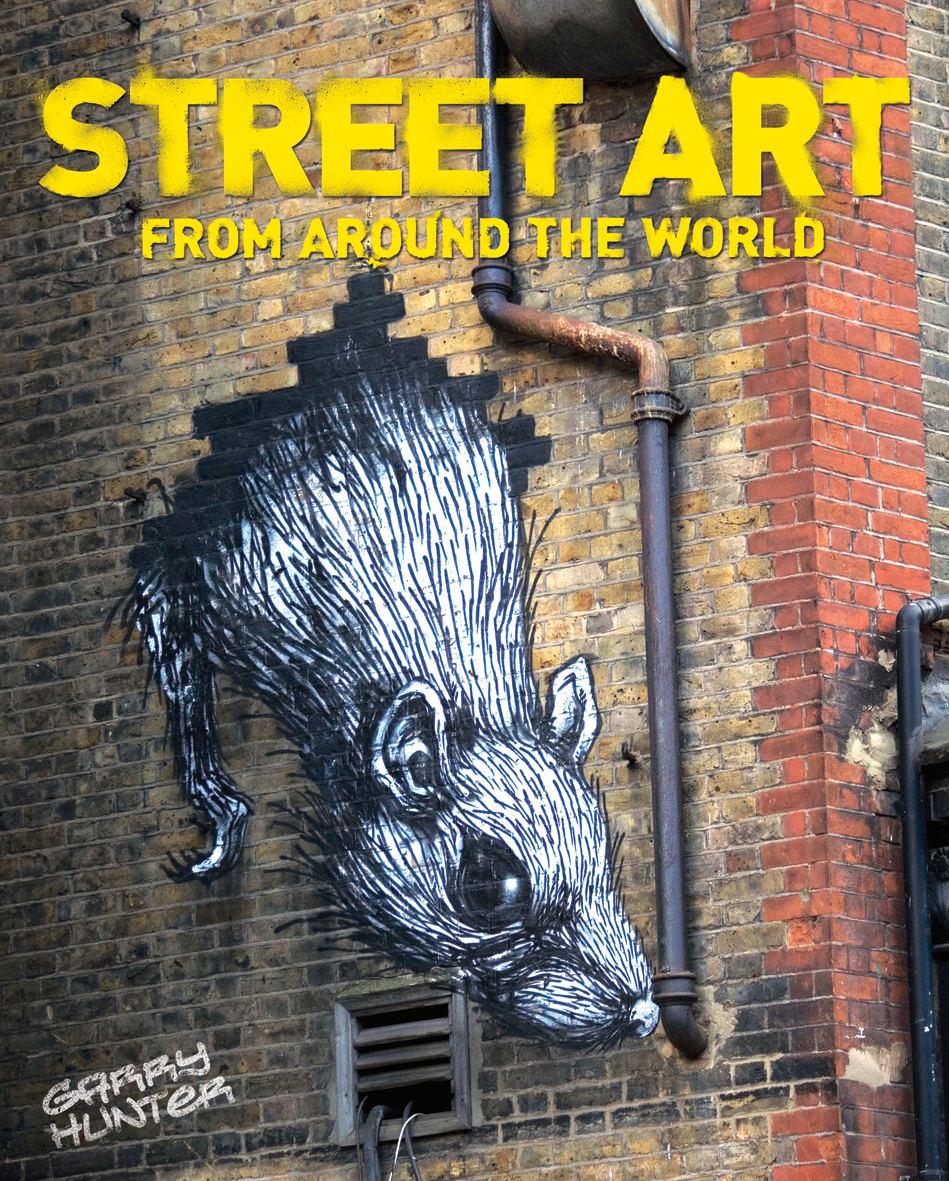

This edition published in 2012 by Arcturus Publishing Limited

26/27 Bickels Yard, 151153 Bermondsey Street,

London SE1 3HA

Copyright 2012 Arcturus Publishing Limited

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person or persons who do any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

eISBN: 978-1-78212-667-6

AD002317EN

Contents

The author would like to thank the following for their support in the making of this book:

London

Manuel Sanmartin

Lucietta Williams

Graham Carrick

Ben Wilson

Julia Elmore

Dan Jones

ROA

Paul Don Smith

The Gentle Author

Matt Brown at Londonist

Sarah Hewson and John Burton at Urban Space

Trinity Buoy Wharf Trust

New York City

Steven P. Harrington and Jaime Rojo at

BrooklynStreetArt.com

Bristol

Morwenna, Olive and Richard Buck

Andy Adams

Berlin

Doralba Picerno

Newcastle

Lazarides Gallery

Sheffield

Michael Lindley

Brazil

Zezo

New Zealand

Bruce Mahalski

Sheridan Orr

West Africa

Angela Walker and Tom Sampson

Artists whose work is reproduced in this book have been identified and credited wherever possible, though due to the nature of street art some works remain anonymous. The publisher will be happy to incorporate proven attributions into future editions.

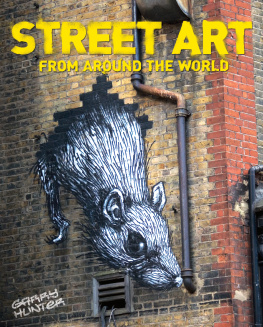

INTRODUCTION

A ll around us, in the urban centres across the world, a creative phenomenon is taking place. Our towns and cities are saturated with the imagery of commerce and advertising, but alongside these there are also personal expressions of the modern human condition in the form of works of art on the street, available for everyone to see. Sometimes created under cover of darkness to avoid arrest, they are often considered temporary, being painted over or replaced by another piece within a few days. Increasingly, however, people have begun to recognize the power of this street art as a medium of expression, and its practitioners are coming out of the darkness and working on commissions and exhibiting in art galleries and cultural institutions.

As the 20th century drew to a close, street art was becoming firmly established as an accessible art form that was available to everyone and that went beyond the esoteric tag, the political statement or the religious affirmation. In order to examine this truly global phenomenon it is important to explore its origins at the very beginning of the built environment, when man started to construct his habitat and create territories away from the cave.

A HISTORY OF SELF-EXPRESSION

East Africa is often associated with the emergence of modern humans and it is here that the earliest evidence of the use of paint can be found. Mans first foray into art is thought to have been body painting perhaps as part of hunting and worship rituals using pigments ground from berries and earth, for which evidence has only recently been discovered. As these practices were evolving 300400,000 years ago, we can only imagine the spectacle of the human body as a primeval canvas and it is largely unknown whether the drawings assumed abstract or figurative form.

The Chauvet-Pont-dArc cave in the Ardche region of France contains the oldest known examples of figurative painting and small 3D sculptures of the female human form, work that dates back at least 35,000 years. The animals depicted here may be totemic ancestors or spirit guides, framed within the hunter-gatherers experience of territory, family, threats and defence, and the fertility of both land and man.

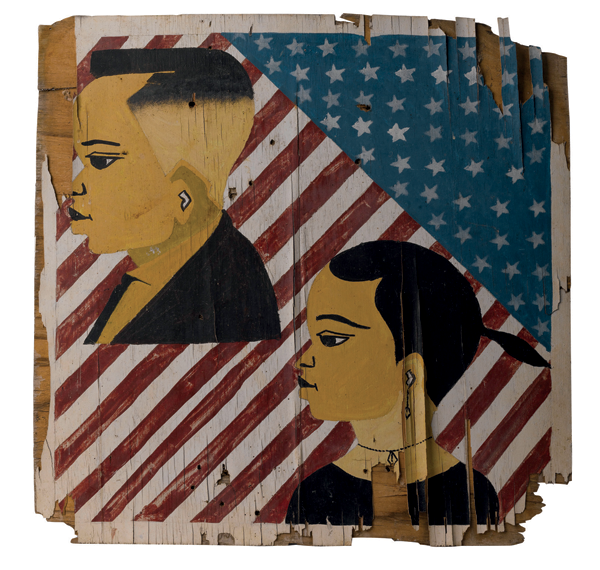

The oldest known graffiti was carved by Semitic soldiers on an Egyptian cliff wall 4,000 years ago. It consists of two inscriptions that appear to contain a mans name and a reference to God, and they represent the creative actions of individuals set apart from officially sanctioned hieroglyphics. Scratching into surfaces as a means of expression is still used throughout the continent in some places, as can be seen in the example above, which marks the arrival of television in West Africa in the late 1970s.

This Paleolithic painting of a bull at the Lascaux cave complex in France is one of the oldest known examples of figurative art in existence.

A television motif scratched into a wall in Niger, 1979: an example of how graffiti is used to mark social change.

There are also many early examples of wall scratching in regions that were seen as cradles of civilization, such as the early metropolitan areas of Ancient Greece and Mesopotamia. Deriving its etymological roots from the Greek word graphein meaning to scratch, draw or write, graffiti was also used in Ancient Rome as a common sign for secret societies, including early Christians who employed a simple fish symbol. This would appear temporarily chalked on subterranean routes to gatherings. It was also used as a test to identify others of the same faith when meeting on the street if a curved sweep of the foot was answered with the reciprocal action that completed the fish cipher in road dust, further communication was safe. By their very transient nature, these moveable motifs provided a means of tacit communication in the earliest urban jungles and revealed coded trails that led to secret locations where various rites could be performed. In the event of discovery these ciphers could be easily disguised or removed.

As civilization developed, permanent figurative symbols became the simple method by which meanings could be communicated to a largely illiterate populace. These could involve the marking of territories or have political and religious significance within a pictorial narrative, or simply visually describe the name of a public house or a shop specializing in particular items. Examples of this can still be seen in Madrid, where, for instance, an image of a mail wagon lies above the road sign for Calle de Postas, an example of dual public information employed since medieval times. The power of these simple images still informs and inspires the creation of much street art, the largely figurative content of which can be read easily in any language and does not require words.

A street sign for a barbers shop in Senegal.

Carved symbols with anti-establishment content were popular in Shakespeares time and many became ingrained in the structure of the Tower of London and other prisons as the accused awaited their fate. More recently, the journal Antiquity reported that drawings found in 2011 on walls in a property in London that was once occupied by members of the 1970s punk rock band The Sex Pistols are worth preserving and have as much cultural importance as ancient cave paintings.

WHAT IS MODERN STREET ART?

This Paleolithic painting of a bull at the Lascaux cave complex in France is one of the oldest known examples of figurative art in existence.

This Paleolithic painting of a bull at the Lascaux cave complex in France is one of the oldest known examples of figurative art in existence. A television motif scratched into a wall in Niger, 1979: an example of how graffiti is used to mark social change.

A television motif scratched into a wall in Niger, 1979: an example of how graffiti is used to mark social change.  A street sign for a barbers shop in Senegal.

A street sign for a barbers shop in Senegal.