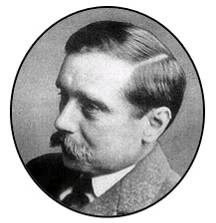

The Complete Works of

H. G. WELLS

(1886-1946)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2015

Version 7

The Complete Works of

H. G. WELLS

By Delphi Classics, 2015

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of H. G. Wells

First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2015.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

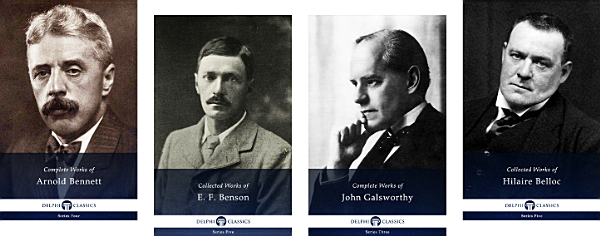

Interested in Edwardian literature?

Then youll love these eBooks

For the first time in publishing history, Delphi Classics is proud to present the complete works of these contemporary authors, with beautiful illustrations and the usual bonus material.

www.delphiclassics.com

The Novels

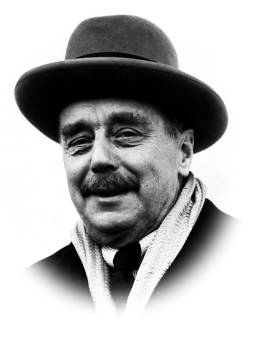

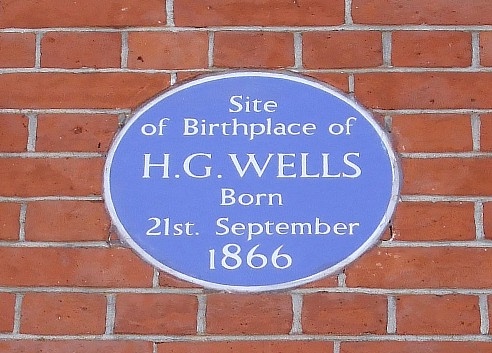

Bromley, where Wells was born in 1866 Wells birthplace was in Atlas House, 46 High Street (on the left in the picture above), which has since been demolished

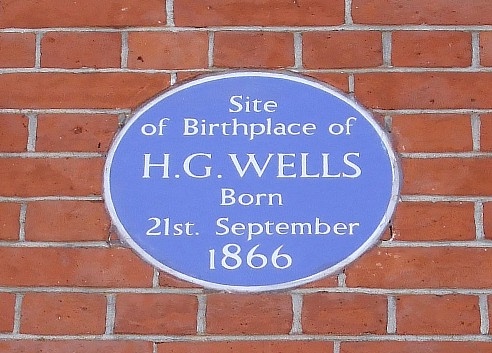

Plaque commemorating Wells birthplace

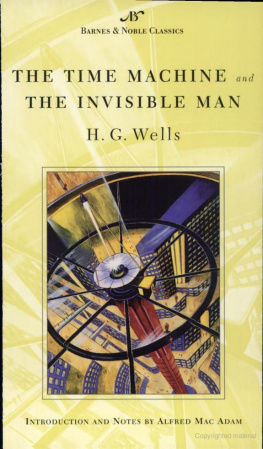

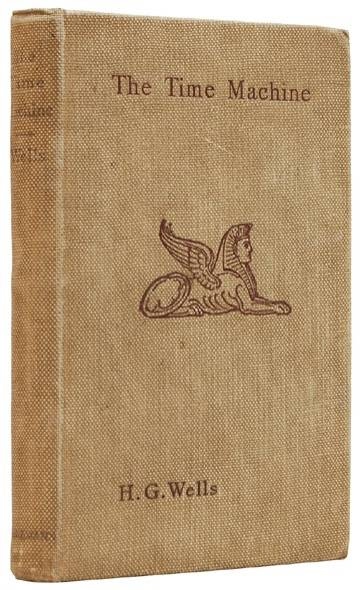

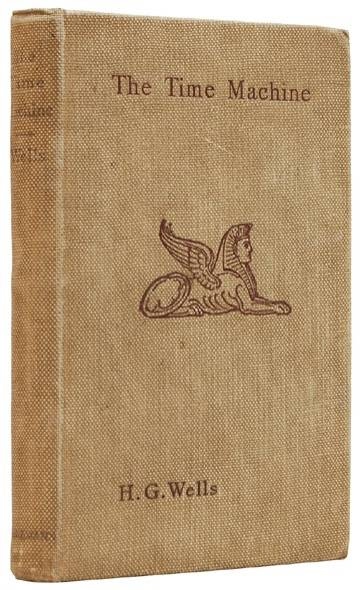

THE TIME MACHINE

Published in 1895, Wells first novel is also his most famous and one of his most successful. In part an expansion of an earlier short story, The Chronic Argonauts (1888), The novel involves an unnamed Time Traveller who claims to have invented a machine for transcending the fourth dimension. He tells his enthralled (but sceptical) listeners how he has used his machine to travel to the year A.D. 802, 701. There, in the ruins of London, he meets the Eloi, a benign race that inhabit what appears to be a utopian, almost child-like society. Soon, however, he discovers that the Eloi are actually at the mercy of the bestial Morlocks ape-like creatures, who live underground.

Critics have read the plight of the Eloi as a metaphor for the idea of racial degeneration a very topical issue during the late-Victorian period. Arising out of a contemporary understanding of Darwins theory of evolution, the idea of degeneration posited that a race was quite as capable of regressing down the evolutionary ladder into less sophisticated forms of biological life, as it was of progressing into more sophisticated forms. Wells had expressed his endorsement of this theory in his essay Zoological Retrogression (1891). In the novel, the Time Traveller suspects that the Morlocks are the descendants of the oppressed working classes of his own time, who similarly live in horrendous conditions in Londons dark slums. Similarly, he hypothesises, the Eloi are the degenerate relatives of the rich capitalists and aristocrats of his own day. The novel thus uses Victorian science to make a social point about the potentially bloody consequences of capitalist oppression (albeit one that arguably fails to present the oppressed worker in a favourable light!)

The novel also grapples memorably with the notion of deep time (also known as geological time). Although a commonplace enough idea today, the notion that the Earth was an ancient planet in an even more impossibly ancient universe was one that had received widespread endorsement only relatively recently at the time of the novels publication. Wells portentous prose makes full dramatic use of the pessimistic implications of the idea and of the insignificance of the Earth and of human life in the grand scheme of things. This is most obvious in the novels memorable final section, where the Time Traveller travels forwards in time to witness the very last days of the planet, underneath a cooling sun; a hypothesis derived from a contemporary understanding of thermodynamics, which conjectured that the Earths final destruction would come about through the inevitable depletion of all energy in the universe.

The first edition

CONTENTS

Poster for the 1960 film adaptation by George Pal probably the most famous screen adaptation of the novel

I

The Time Traveller (for so it will be convenient to speak of him) was expounding a recondite matter to us. His grey eyes shone and twinkled, and his usually pale face was flushed and animated. The fire burned brightly, and the soft radiance of the incandescent lights in the lilies of silver caught the bubbles that flashed and passed in our glasses. Our chairs, being his patents, embraced and caressed us rather than submitted to be sat upon, and there was that luxurious after-dinner atmosphere when thought roams gracefully free of the trammels of precision. And he put it to us in this way marking the points with a lean forefinger as we sat and lazily admired his earnestness over this new paradox (as we thought it) and his fecundity.

You must follow me carefully. I shall have to controvert one or two ideas that are almost universally accepted. The geometry, for instance, they taught you at school is founded on a misconception.

Is not that rather a large thing to expect us to begin upon? said Filby, an argumentative person with red hair.

I do not mean to ask you to accept anything without reasonable ground for it. You will soon admit as much as I need from you. You know of course that a mathematical line, a line of thickness nil , has no real existence. They taught you that? Neither has a mathematical plane. These things are mere abstractions.

That is all right, said the Psychologist.

Nor, having only length, breadth, and thickness, can a cube have a real existence.

There I object, said Filby. Of course a solid body may exist. All real things

So most people think. But wait a moment. Can an instantaneous cube exist?

Dont follow you, said Filby.

Can a cube that does not last for any time at all, have a real existence?

Filby became pensive. Clearly, the Time Traveller proceeded, any real body must have extension in four directions: it must have Length, Breadth, Thickness, and Duration. But through a natural infirmity of the flesh, which I will explain to you in a moment, we incline to overlook this fact. There are really four dimensions, three which we call the three planes of Space, and a fourth, Time. There is, however, a tendency to draw an unreal distinction between the former three dimensions and the latter, because it happens that our consciousness moves intermittently in one direction along the latter from the beginning to the end of our lives.

Next page