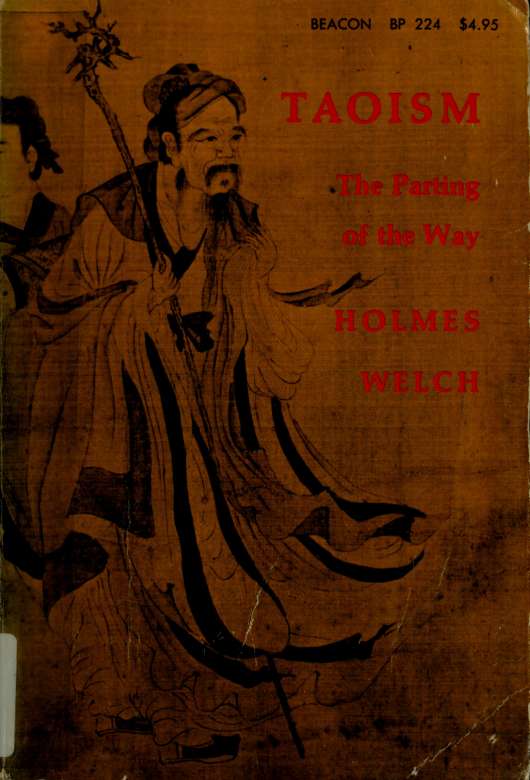

Holmes H. Welch Jr. - Taoism. the parting of the way

Here you can read online Holmes H. Welch Jr. - Taoism. the parting of the way full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Boston, year: 1966, publisher: Beacon Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Taoism. the parting of the way

- Author:

- Publisher:Beacon Press

- Genre:

- Year:1966

- City:Boston

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Taoism. the parting of the way: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Taoism. the parting of the way" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Taoism. the parting of the way — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Taoism. the parting of the way" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

Ackjiowledgements

Permission was kindly given by the publishers to quote from the following:

George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Arthur Waley, The Way and Its Power, 1933 Cambridge University Press

Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, 1956 Harper & Brothers

Kirsopp Lake, Introduction to the New Testament, 1937

Aldous Huxley, Doors of Perception, 1954 Houghton Mifflin Company

Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams, 1918

Ruth Benedict, Patterns of Culture, 1934 The Macmillan Company

F. C. S. Northrop, Meeting of East and West, 1946 The New Yorker

New Yorker, November 14, 1953 Princeton University Press

Fung Yu-lan, A History of Chinese Philosophy, 1937, 1953 Arthur Probathain

J. J. L. Duyvendak, The Book of Lord Shang, 1928 Random House

Lin Yutang, The Wisdom of China and India, 1942 Routledge & Kegan Paul

Arthur Waley, Travels of an Alchemist, 1931 Simon & Schuster

Edward R. Murrow, This I Believe, 1952

William H. Whyte, Is Anybody Listening?, 1952 The University of Chicago Press

Foreword

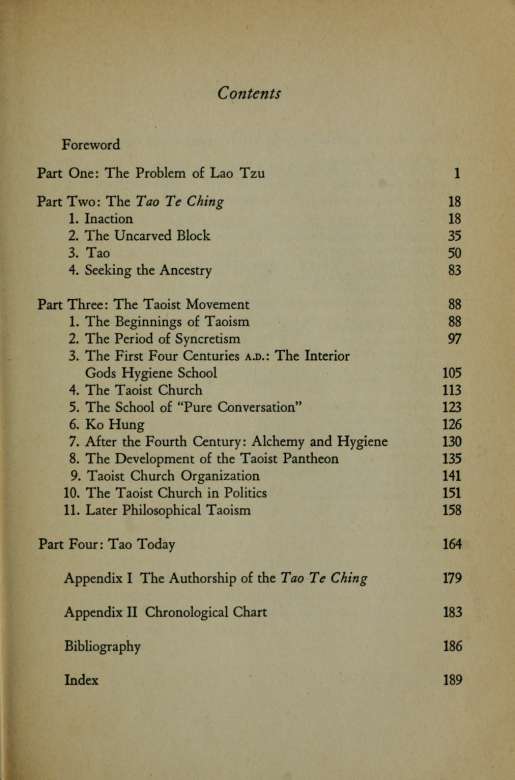

This book is not intended to be a contribution to Sinology, but to public understanding of the Chinese point of view, one component of which is Taoism. It is written in four parts. The first explains a fact which some translators have concealed from their readers: that neither they nor anyone else can be sure what Lao Tzu was talking about. Part Two explains what / think he was talking about. Part Three takes up the vast and curious movement which claimed him as its founder. Part Four tests his teachings on the problems of today. The third part on the Taoist movement must be read with particular caution. The subject is infinitely complicated; the information is difficult to get at; and mistakes are easy to make.

The reader may be disappointed to find that this volume does not include a complete translation of Lao Tzu. Since we already have thirty-six in English, it hardly seemed necessary. The fact is that no translation can be satisfactory in itself because no translation can be as ambiguous as the Chinese original. However, because I have taken an analytical approach, I owe an apology to Lao Tzu. He believed that many of his most important ideas could not be put into words. That is why he so often sounds ambiguous. I shall attempt to express them unequivocally and directly, which is at best presumptuous. Lao Tzu's teaching methods were intuitive. He put a low price on system and formal logic. I shall attempt to give his philosophy a logical and systematic form, demonstrating that I have not learned one of the lessons Lao Tzu teaches, that "the good man does not prove by argument."

I want to thank the following persons for the help they have given me in preparing this book: Chang Hsin-pao, Henry D. Burnham, Mrs. Arland Parsons, William Hung, James R. Hightower, Kenneth Ch'en, Ch'ii T'ung-tsu, and Arthur Waley.

Stowe, Vermont Holmes Welch

March, 1957

Foreword to This Edition

Since there is still no convenient synopsis of the various aspects of Taoism written in EngUsh, the present volume is being reissued. I have not attempted to update or revise it completely, but only to make changes that seemed important and typographically possible and to eliminate certain superfluities.

Holmes Welch Cambridge, Massachusetts December, 1965

TAOISM

Part One: THE PROBLEM OF LAO TZU

As to the Sage, no one will know whether he existed or not. Lao Tzu

There is a legend that on the fourteenth of September, 604 b.c, in the village of Ch'ii Jen in the county of K'u and the Kingdom of Ch'u, a woman, leaning against a plum tree, gave birth to a child. Since this child was to be a great mana god, no lessthe circumstances of his birth were out of the ordinary. He had been conceived some sixty-two years before when his mother had admired a falling star, and after so many years in the womb, he was able to speak as soon as he was born. Pointing to the plum tree, he announced: "I take my surname from this tree." To Plum (Li) he prefixed Ear (Erh)his being largeand so became Li Erh. However, since his hair was already snow-white, most people called him Lao Tzu, or Old Boy. After he died they called him Lao Tan, "Tan" meaning "long-lobed."

About his youth little is told. We learn, however, that he spent his later years in the Chinese Imperial capital at Loyang, first as Palace Secretary and then as Keeper of the Archives for the Court of Chou. Evidently he married, for he had a son, Tsung, who became a successful soldier under the Wei and through whom later generations, like the T'ang emperors, traced their descent from Lao Tzu.

Though he made no effort to start a school, people came of their own accord to become his disciples. Confucius, who was some fifty-three years his junior, had one or perhaps several meetings with him and does not appear to have given too good an account of himself. In 517 B.C. Lao Tzu closed their meeting by saying: "I have heard it said that a clever merchant, though possessed of great hoards of wealth, will act as though his coffers were empty: and that the princely man, though of perfect moral excellence, maintains the air of a simpleton. Abandon your arrogant ways and countless desires, your suave demeanour and unbridled ambition, for they do not promote your welfare. That is all I have to say to you." At which Confucius went away, shaking his head, and said to his disciples: "I understand how birds can fly, how fishes can swim, and how four-footed beasts can run. Those than run can be snared, those that swim may be caught with

hook and line, those that fly may be shot with arrows. But when it comes to the dragon, I am unable to conceive how he can soar into the sky riding upon the wind and clouds. Today I have seen Lao Tzu and can only liken him to a dragon."

At the age of 160 Lao Tzu grew disgusted with the decay of the Chou dynasty^ and resolved to pursue virtue in a more congenial at-mocphere. Riding in a chariot drawn by a black ox, he left the Middle Kingdom through the Han-ku Pass which leads westward from Loyang. The Keeper of the Pass, Yin Hsi, who, from the state of the weather, had expected a sage, addressed him as follows: "You are about to withdraw yourself from sight. I pray you to compose a book for me." Lao Tzu thereupon wrote the 5,000 characters which we call the Tao Te Ching? After completing the book, he departed for the west. We do not know when or where he died. But a last glimpse is given us in a late source, influenced by Buddhism, which describes his first three nights in the mountains beyond the pass. Lying under a mulberry tree he was tempted by the Evil One and by beautiful women. Lao Tzu did not find it hard to resist temptation, however, since to him the beautiful women were only "so many skin-bags full of blood."

The biography I have just given does not represent a consensus of all our sources. Actually, there can be no such consensus because different sources tell different stories. Possibly Lao Tzu was born not in 604 B.C., but in 571 b.c.; not in Ch'u, but in Ch'en. He may have spent not 62, but 81 years in his mother's womb and departed for the west at the age of 200, not 160. Possibly he was not even a contemporary of Confucius, but identical with Lao Tan, a Keeper of the Archives who we know held ofiice at the court of Chou about 374 b.c; or, on the other hand, he may be identical with one Lao Lai Tzu who figures in stories about Confucius and wrote a book (which has not survived) in

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Taoism. the parting of the way»

Look at similar books to Taoism. the parting of the way. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Taoism. the parting of the way and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.