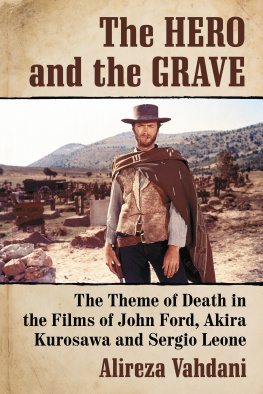

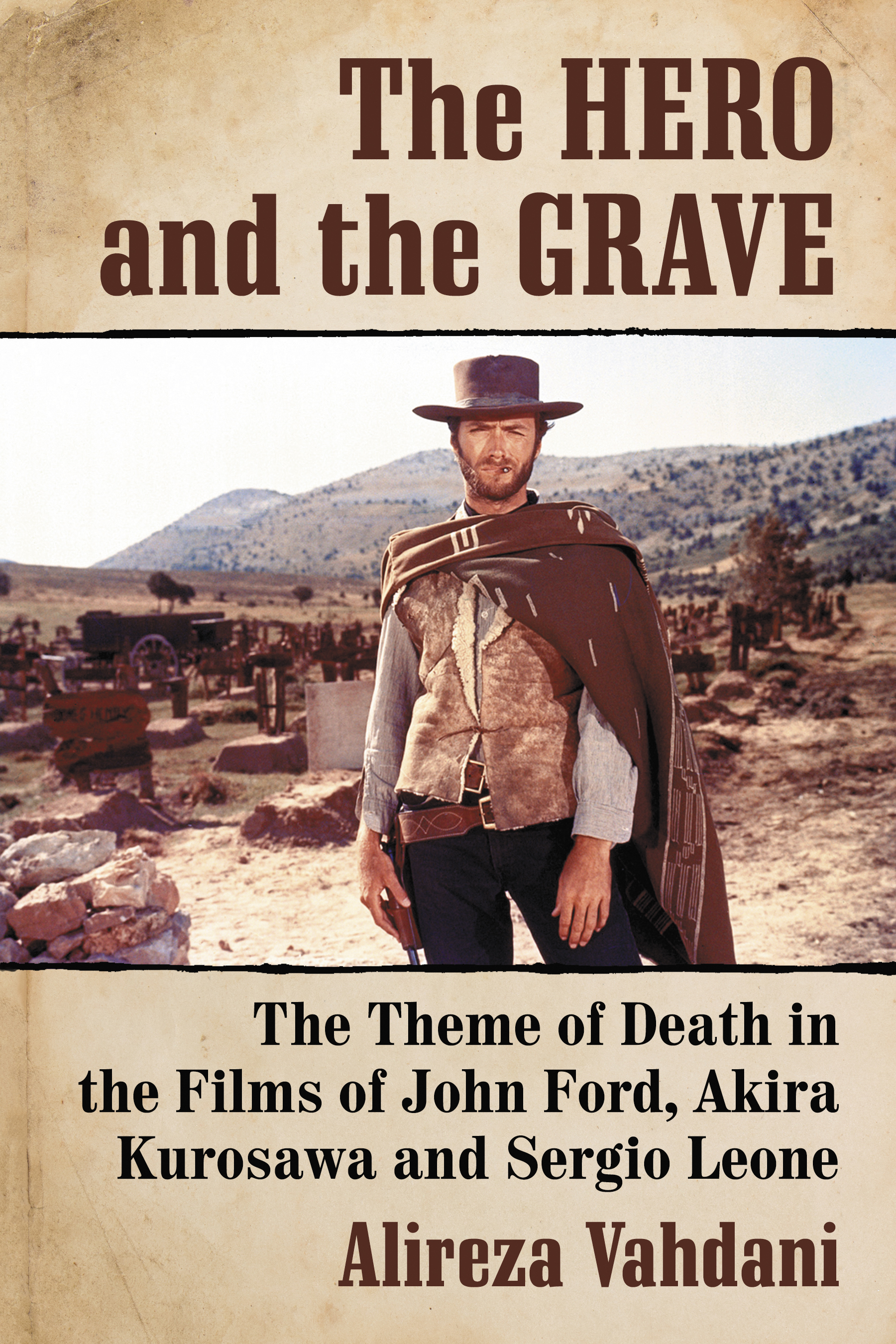

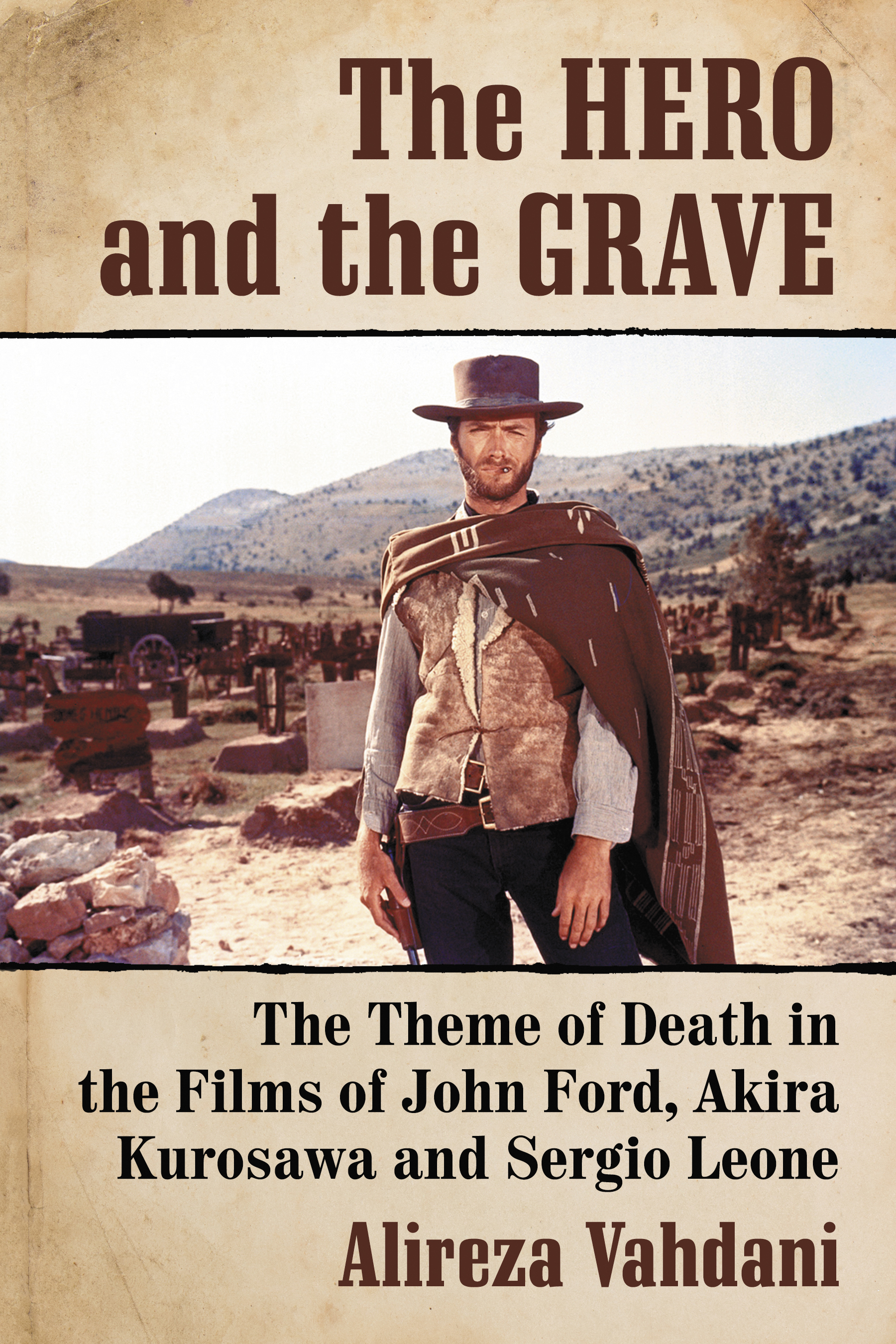

The Hero and the Grave

The Theme of Death in the Films of John Ford, Akira Kurosawa and Sergio Leone

Alireza Vahdani

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3354-1

2018 Alireza Vahdani. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: Clint Eastwood in the 1966 film The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (MGM/Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To the memory of my parents

Acknowledgments

I thank the following people for their input: Bahram Vahdani, Ali Vahdani, Behnam Vahdani, Alberto Mira, Alexander Jacoby, Dylan Lightfoot, Andrew Moriarty, Sarah Cheeseman, Benedict Van der Linde, Nikki Greene and Robin Alvarez. I also thank the anonymous readers who provided feedback on an early draft. Without all of these people, it would not have been possible to bring this book to fruition.

Introduction

Death is not the end or the beginning. Rather, it is a process. In relation to fiction films, the theme of death is one of the essential plot devices that can begin the storyline, create a turning point in the plot, imbue the film with certain political assumptions or clarify its moral outlook. In doing so, the theme of death evolves into a narrative strategy that can either challenge the heros position within the plot or reshape it.

Boaz Hagin (2010, p. 1), in Death in Classical Hollywood Cinema, writes, The question of whether death [in films] is, or should be, meaningful in general is far from settled. In this book, I will study and compare the different ways in which the theme of death impacts the narratives of John Fords and Sergio Leones Westerns and Akira Kurosawas jidaigeki films. In particular, I will pay close attention to how the heros death, or his response to the threat of death, affects his position in the narrative. I am not interested in the stylistic similarities and differences between the films of these directors. Rather, I am concerned with the thematic similarities and differences. Christopher Frayling, Jim Kitses, Donald Richie, and Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto have written specificity about the influence of Fords style on Kurosawas films, as well as the impact of Fords and Kurosawas films on Leones spaghetti Westerns. More recently, John Fawell, in The Art of Sergio Leones Once Upon a Time in the West: A Critical Appreciation (2005), has explained in great depth how Fords approach to landscape influenced Leones filmmaking style.

The obsession with how, for example, Fords style influenced the final look of a Kurosawa or Leone film is not limited to film scholars. Kurosawa, in both his autobiography (1983) and interviews, explained the extent to which the style of Fords films influenced his samurai films: I have respected John Ford from the beginning. I pay close attention to his productions, and I think I am influenced by them Western dramas have been filmed over and over again for a very long time and in the process, have evolved a kind of grammar of cinema. And I have learned from this grammar (Cardullo, 2008, pp. 2425). Furthermore, Leone pointed out that his interest in making Westerns originated with John Fords Westerns. In his interview with Frayling in Once Upon a Time in Italy (2008, p. 81), Leone said, I could almost say that it was thanks to him [John Ford] that I even considered making Westerns myself. There is a visual influence there as well because he [Ford] was the one who tried most carefully to find a true visual image to stand for the West. Leone went on to explain the influence of Fords style on his Italian Westerns: I can guarantee that the characters who register strongly in front of distant horizons in my WesternsWesterns that are in many respects more cruel and definitely less innocent and enchanted than [Fords] owe a great deal to his lessons in cinematic form, even if the debt is involuntary (Frayling, 2008, p. 168).

Ford engaged with several prominent social and political themes from classic Western films, such as history versus myth, nomads versus settlers, individualism versus community, the clash of moralities, the historical and political expansions of a nation, and so forth. Kurosawa and Leone likewise argued that throughout their respective careers they engaged with themes that changed the norms of samurai films and spaghetti Westerns. Regarding Kurosawa, the common belief among scholars such as Prince, Richie, and Yoshimoto is that although Kurosawa was concerned with Japanese history and culture, his films were mainly influenced by the themes that Ford promoted in his Westerns. Prince, in The Warriors Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa (1991, pp. 1213), writes that [b]oth men [Ford and Kurosawa] were attracted to stories of masculine adventure (though, perhaps, Kurosawa more consistently than Ford); both men continued to rely on a stock company of trusted performers; and both men, of course, had a certain regard for Westerns. Moreover, Kurosawas films effectively revolutionized Japanese period films. Joan Mellen, in Voice from the Japanese Cinema (1975, p. 37), writes on this point, If [Daisuke] Ito [18981981] created the genre of jidaigeki, Kurosawa perfected the form and gave it so deep a historical resonance that each of his jidaigeki has contained within it the entire progress of Japan from feudal to modern times.

Studying Sergio Leones films in tandem with works of Ford and Kurosawa shows the final stages of the evolution of theme of death in Western/samurai films. Ford and Kurosawas attitudes toward the standard Western themes and concerns greatly influenced Leones Italian Westerns. Also, the critical attitude of spaghetti Westerns regarding familiar themes of the classic Westerns or samurai films (such as the heros codes of conduct, the moral decency of the family and the social ethics of the community) suggests that Leones films developed a language of their own. This language offers a different outlook on the American history and myth than Fords Western films.

Western and samurai films are action packed, further emphasizing the role of death with regard to the moralities that these genres project in relation to the history of America and Japan. In these cinematic texts, the heros response to the presence and, indeed, the absence of death as a physical, historical or social threat strengthens or criticizes these moralities. Even though the death of a character results in his or her absence from the mise en scne, their past actions can still affect the films conclusion.

The existing literature on the works of Ford, Kurosawa, and Leone has not studied the effect of the theme of death on the position of the hero in their films in a detailed and focused fashion. However, film scholars such as Austin Fisher, Frayling, Kitses, Prince, and Richie have created valuable literature on each directors films. They have observed and studied the works of these directors in different theories and contexts: auteurism, cultural and social studies, historical studies and so on. Closer to a thematic study of death, the above scholars have also written on violence and its social and aesthetic qualities in the films of Ford, Kurosawa, and Leone. In recent years, Mary Lea Bandy and Kevin Stoehr, in

Next page