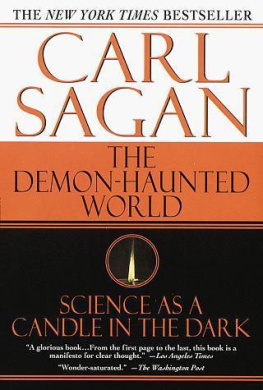

The

Demon-Haunted

World

Science as a Candle

in the Dark

Carl Sagan

To Tonio,

My grandson.

I wish you a world

Free of demons

And full of light.

We wait for light, but behold darkness.

Isaiah 59:9

It is better to light one candle than to curse the darkness.

Adage

Preface

My Teachers

I t was a blustery fall day in 1939. In the streets outside the apartment building, fallen leaves were swirling in little whirlwinds, each with a life of its own. It was good to be inside and warm and safe, with my mother preparing dinner in the next room. In our apartment there were no older kids who picked on you for no reason. Just the week before, I had been in a fight - I cant remember, after all these years, who it was with; maybe it was Snoony Agata from the third floor - and, after a wild swing, I found I had put my fist through the plate glass window of Schechters drug store.

Mr Schechter was solicitous: Its all right, Im insured, he said as he put some unbelievably painful antiseptic on my wrist. My mother took me to the doctor whose office was on the ground floor of our building. With a pair of tweezers, he pulled out a fragment of glass. Using needle and thread, he sewed two stitches.

Two stitches! my father had repeated later that night. He knew about stitches, because he was a cutter in the garment industry; his job was to use a very scary power saw to cut out patterns - backs, say, or sleeves for ladies coats and suits - from an enormous stack of cloth. Then the patterns were conveyed to endless rows of women sitting at sewing machines. He was pleased I had gotten angry enough to overcome a natural timidity.

Sometimes it was good to fight back. I hadnt planned to do anything violent. It just happened. One moment Snoony was pushing me and the next moment my fist was through Mr Schechters window. I had injured my wrist, generated an unexpected medical expense, broken a plate glass window, and no one was mad at me. As for Snoony, he was more friendly than ever.

I puzzled over what the lesson was. But it was much more pleasant to work it out up here in the warmth of the apartment, gazing out through the living-room window into Lower New York Bay, than to risk some new misadventure on the streets below.

As she often did, my mother had changed her clothes and made up her face in anticipation of my fathers arrival. We talked about my fight with Snoony. The Sun was almost setting and together we looked out across the choppy waters.

There are people fighting out there, killing each other, she said, waving vaguely across the Atlantic. I peered intently.

I know, I replied. I can see them.

No, you cant, she replied, sceptically, almost severely, before returning to the kitchen. Theyre too far away.

How could she know whether I could see them or not? I wondered. Squinting, I had thought Id made out a thin strip of land at the horizon on which tiny figures were pushing and shoving and duelling with swords as they did in my comic books. But maybe she was right. Maybe it had just been my imagination, a little like the midnight monsters that still, on occasion, awakened me from a deep sleep, my pyjamas drenched in sweat, my heart pounding.

How can you tell when someone is only imagining? I gazed out across the grey waters until night fell and I was called to wash my hands for dinner. When he came home, my father swooped me up in his arms. I could feel the cold of the outside world against his one-day growth of beard.

On a Sunday in that same year, my father had patiently explained to me about zero as a placeholder in arithmetic, about the wicked-sounding names of big numbers, and about how theres no biggest number (You can always add one, he pointed out). Suddenly, I was seized by a childish compulsion to write in sequence all the integers from 1 to 1,000. We had no pads of paper, but my father offered up the stack of grey cardboards he had been saving from when his shirts were sent to the laundry. I started the project eagerly, but was surprised at how slowly it went. When I had gotten no farther than the low hundreds, my mother announced that it was time for me to take my bath. I was disconsolate. I had to get a thousand. A mediator his whole life, my father intervened: if I would cheerfully submit to the bath, he would continue the sequence. I was overjoyed. By the time I emerged, he was approaching 900, and I was able to reach 1,000 only a little past my ordinary bedtime. The magnitude of large numbers has never ceased to impress me.

Also in 1939 my parents took me to the New York Worlds Fair. There, I was offered a vision of a perfect future made possible by science and high technology. A time capsule was buried, packed with artefacts of our time for the benefit of those in the far future -who, astonishingly, might not know much about the people of 1939. The World of Tomorrow would be sleek, clean, streamlined and, as far as I could tell, without a trace of poor people.

See sound one exhibit bewilderingly commanded. And sure enough, when the tuning fork was struck by the little hammer, a beautiful sine wave marched across the oscilloscope screen. Hear light another poster exhorted. And sure enough, when the flashlight shone on the photocell, I could hear something like the static on our Motorola radio set when the dial was between stations. Plainly the world held wonders of a kind I had never guessed. How could a tone become a picture and light become a noise?

My parents were not scientists. They knew almost nothing about science. But in introducing me simultaneously to scepticism and to wonder, they taught me the two uneasily cohabiting modes of thought that are central to the scientific method. They were only one step out of poverty. But when I announced that I wanted to be an astronomer, I received unqualified support - even if they (as I) had only the most rudimentary idea of what an astronomer does. They never suggested that, all things considered, it might be better to be a doctor or a lawyer.

I wish I could tell you about inspirational teachers in science from my elementary or junior high or high school days. But as I think back on it, there were none. There was rote memorization about the Periodic Table of the Elements, levers and inclined planes, green plant photosynthesis, and the difference between anthracite and bituminous coal. But there was no soaring sense of wonder, no hint of an evolutionary perspective, and nothing about mistaken ideas that everybody had once believed. In high school laboratory courses, there was an answer we were supposed to get. We were marked off if we didnt get it. There was no encouragement to pursue our own interests or hunches or conceptual mistakes. In the backs of textbooks there was material you could tell was interesting. The school year would always end before we got to it. You could find wonderful books on astronomy, say, in the libraries, but not in the classroom. Long division was taught as a set of rules from a cookbook, with no explanation of how this particular sequence of short divisions, multiplications and subtractions got you the right answer. In high school, extracting square roots was offered reverentially, as if it were a method once handed down from Mt Sinai. It was our job merely to remember what we had been commanded. Get the right answer, and never mind that you dont understand what youre doing. I had a very capable second-year algebra teacher from whom I learned much mathematics; but he was also a bully who enjoyed reducing young women to tears. My interest in science was maintained through all those school years by reading books and magazines on science fact and fiction.

College was the fulfilment of my dreams: I found teachers who not only understood science, but who were actually able to explain it. I was lucky enough to attend one of the great institutions of learning of the time, the University of Chicago. I was a physics student in a department orbiting around Enrico Fermi; I discovered what true mathematical elegance is from Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar; I was given the chance to talk chemistry with Harold Urey; over summers I was apprenticed in biology to H.J. Muller at Indiana University; and I learned planetary astronomy from its only full-time practitioner at the time, G.P. Kuiper.

Next page