The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Introduced by Daniel Alarcn

Introduced by Ann Beattie

Introduced by David Bezmozgis

Introduced by Lydia Davis

Introduced by Dave Eggers

Introduced by Jeffrey Eugenides

Introduced by Mary Gaitskill

Introduced by Aleksandar Hemon

Introduced by Amy Hempel

Introduced by Jonathan Lethem

Introduced by Sam Lipsyte

Introduced by Ben Marcus

Introduced by David Means

Introduced by Lorrie Moore

Introduced by Daniel Orozco

Introduced by Norman Rush

Introduced by Mona Simpson

Introduced by Ali Smith

Introduced by Wells Tower

Introduced by Joy Williams

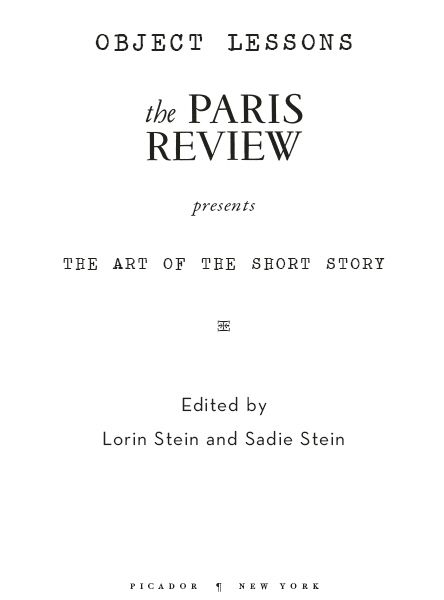

Editors Note Since its founding, in 1953, The Paris Review has been a laboratory for new fiction. The editors have never believed that there was one single way to write a story. Weve never espoused a movement or school. Weve never observed a word limit. We think every good story writes its own rules and solves problems of its own devising.

Thats the idea behind this book. It is not a greatest hits anthology. Instead, we asked twenty masters of the genre to choose a story from The Paris Review archivesa personal favoriteand to describe the key to its success as a work of fiction. Some chose classics. Some chose stories that were new even to us.

Our hope is that this collection will be useful to young writers, and to others interested in literary technique. Most of all, it is intended for readers who are not (or are no longer) in the habit of reading short stories. We hope these object lessons will remind them how varied the form can be, how vital it remains, and how much pleasure it can give.

Daniel Alarcn

on

Joy Williamss Dimmer Joy Williams is one of those unique and instantly recognizable storytelling voices, capable of finding the mysterious and magical heart within even the most ordinary human acts. Her stories begin in unexpected places, and take surprising turns toward their eventual end. She doesnt describe life; she exposes it. She doesnt write scenes, she evokes them with a finely observed gesture, casually reinterpreted to provide maximum, often devastating, insight: He had straddled the baby as it crept across the ground as though little Mal were a gulch he had no intention of falling into.

The baby in this startling image is Mal Vester, the unlucky and unloved protagonist of Dimmer. He is a survivor, but there is no romantic luster to his suffering. Mal is rough, untamed, stricken, desperate, and alone. His father, who never wanted him, dies in the first sentence; his mother, the only person who loved him without restraint, dies in the second. Her death haunts this beatiful, moving story, right up until the very last line; but what keeps us reading to the end is the prose, which constantly unpacks and explains Mals unlikely world with inventive and striking images. Williams has done something special: she makes Mals drifting, his lack of agency, narratively compelling. Life happens to Mal; it is inflicted upon him, a series of misfortunes that culminate in his exile. (A lonelier airport has never appeared in short fiction.) Mal never speaks, but somehow, I didnt realize it until the third time Id read Dimmer. I knew him so well, felt his tentative joy and fear so intimately, it was as if hed been whispering in my ear all along.

Joy Williams

Dimmer

I

Mal Vester had a pa who died in the Australian desert after drinking all the water from the radiator of his Land Rover. His momma had died just like the coroner said she had, even though he had lost the newspaper clipping that would have proved it. Not lost exactly. He had folded up the story and put it in the pocket of his jeans for one year and one half straight because they were the only pants he had and the paper had turned from print into lint and then into the pocket itself and then the jeans had become as thin and as grey as the egg skins his momma had put over his boils when he was little.

He still had the jeansspread out flat on the bottom of his suitcase but they were just a rag really, not even a rag but just a few threads insufficient even to cover up a cat hit in the street.

The coroner, in absolving anyone or everyone of guilt in Mals mothers death, had stated to the press, represented by a lean young man in a black suit with a nose blue and huge as a Doberman pinscher, that

the murky water and distance from

the shore precluded adequare witnessing of the terminal event. If

the victim were in the process of

having her upper extremity avulsed

by a large fish she would have had

little opportunity to wave or to

render an intelligent vocal ap

praisal of her dealings at that par

ticular moment Death being unavoidable and by misadventure

Mal thought the wording cold but swell.

Everyone had thought she was mucking about. It was dusk and there were hundreds on the beach cooking their meat, the children eating ice-cream pies, the old ones staring into the sun. There was a man washing his greyhounds in a tidal pool. The water was cold and pale, flecked with filthy foam, green like the scum of a chicken stewing. Mal was in the cottage, fixing supper, pouring hot water over the jello powder, browning the moki in the skillet oil, and next door Freddie Gomkin was burning out another clutch as he tried to coax his car up and over the hill to the flat races in Sydney.

It certainly did not seem at the time that anyone could be dying. It was not the season. It was Durbans season.

And no one was really paying any attention. She was by herself in water no deeper than her ribs, 100 feet down the beach from the public conveniences. And she disappeared. Someone later said that they thought they saw her disappearing. But they saw no fin. Blood came shoreward in a little patch, bright and neat as a paper plate. The only thing that Mal Vester had to go on of course was that she never came back. A few days later, someone caught a tiger shark and when they cut it open, there was a bathing costume stamped with a laundry mark wrapped round its intestine. But the laundry mark was traced to a Mrs. Annie White of Toowoomba who was still alive and who worked in a doll hospital.

After it happened, he was unsure that it hadnt. He lay in the cottage and didnt know what to do. His mother always hated the water because she could not swim and because she was convinced that people pissed in it all the time. This had become a minor obsession with her. She went all white and shaky when she saw the women sitting on the sandbank, their legs stretched out into the waves, the water rattling in between their thighs. Mal was eleven and she held him close. The beach was no place to bring up a fatherless child by god she always said. Snorkels and men spitting. Women shuffling behind towels, dropping their clothes. Bleeding and coughing. Hair everywhere and rotting sandwiches. Unmentionables coming in with the tide.

He lay on a rolling cot and struck his hips with a loose fist. The moki was dumped charred into the sink. The clocks ran down. He moped about the cottage, practically starving to death while he thought of his mother and how she smelled. She had sung to himall the American hits

There aint nothing in the world

But a boy and a girl

And love, love, love

Next page