Jack Hunter - Pop Avant-Garde Violence: The Films Of Koji Wakamatsu

Here you can read online Jack Hunter - Pop Avant-Garde Violence: The Films Of Koji Wakamatsu full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: Elektron Ebooks, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

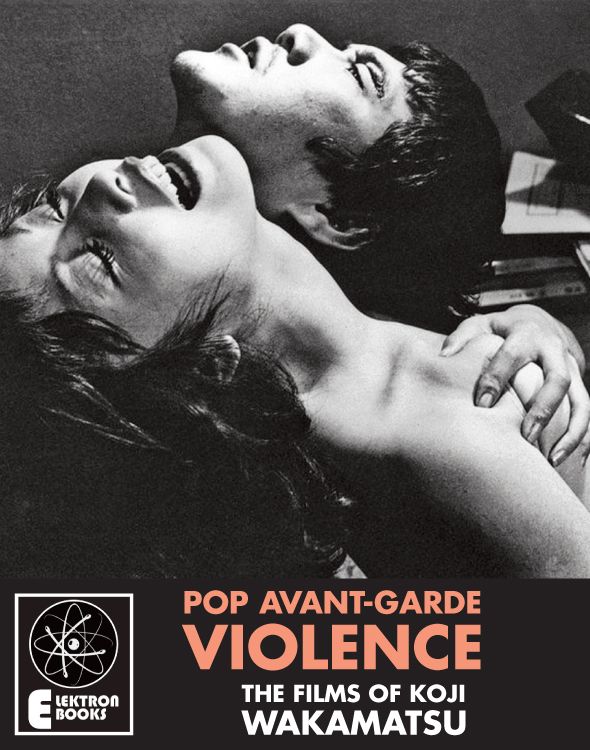

- Book:Pop Avant-Garde Violence: The Films Of Koji Wakamatsu

- Author:

- Publisher:Elektron Ebooks

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pop Avant-Garde Violence: The Films Of Koji Wakamatsu: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Pop Avant-Garde Violence: The Films Of Koji Wakamatsu" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Jack Hunter: author's other books

Who wrote Pop Avant-Garde Violence: The Films Of Koji Wakamatsu? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Pop Avant-Garde Violence: The Films Of Koji Wakamatsu — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Pop Avant-Garde Violence: The Films Of Koji Wakamatsu" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

POP AVANT-GARDE VIOLENCE

BY JACK HUNTER

AN EBOOK

ISBN 978-1-908694-67-6

PUBLISHED BY ELEKTRON EBOOKS

COPYRIGHT 2012 ELEKTRON EBOOKS

www.elektron-ebooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a database or retrieval system, posted on any internet site, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holders. Any such copyright infringement of this publication may result in civil prosecution

Born 1936 in Miyagi Prefecture, Koji Wakamatsu dropped out of Agricultural College in second grade, came to Tokyo and went through a succession of jobs including apprentice craftsman, delivery boy, and would-be gangster with the Shinjuku-based Yasuda-gumi mob the latter activity landing him a spell in prison. Released at the age of 23, he finally became an assistant director for TV films, and in 1963 broke into cinema by directing a proto-pink (erotic) movie called Amai-Wana (Sweet Trap). He soon became renowned as a pulp director, his projects already distinguished by vivid and violent scenes. These early films include Hageshii Onnatachi (Savage Women, 1963), Mesuinu No Kake (The Games Of Bitches, 1964), Hadaka No Kage (The Naked Shadow, 1964), and AkaiHanko (Red Crime, 1964). In Red Crime, the chaste wife of a public attorney is raped by an escaped convict, and the film examines in detail the sexual relations between the three protagonists. Here we can already trace the seminal motifs of Wakamatsus cinema: hatred, disgust for authority, and psycho-sexual disturbance.

By the time Tetsuji Takechis controversial erotic films Daydream (1964) and Black Snow (1965) were released, [1] Wakamatsu had already produced almost 20 films ranging in content from one flavour of the month to the next. Evidently inspired by Takechis revolutionary sex movies and the New Wave films of his spiritual mentor, Nagisa Oshima [2] Wakamatsu, like Seijun Suzuki before him, now decided to indulge these influences within the confines of a Nikkatsu production. The results would have profound repercussions on his career.

The film that Wakamatsu produced Kabe NoNaka No Himegoto (Secret Acts Within Four Walls, 1965) was a radical departure. [3] The original project was supposed to be a film on middle-class students, the pressures of their lives as they prepare for important examinations [4], their social interactions etc. Wakamatsu hijacked the basic framework and filled it with a shocking psychodrama of scopophilia, rape and murder. In this new version, the protagonist is a teenaged student facing his college entrance exams in the knowledge that he is doomed to fail due to his previously poor education. Frustrated and maddened by his inadequacy in the eyes of society, he becomes a compulsive voyeur, masturbating as he spies on various women. One of the objects of his gaze is a rich, middle-class housewife who represents the very society which has scorned him, and which he hates with psychopathic intensity. He breaks into her house and brutally rapes her (despite or perhaps because of her willingness to fuck him). The woman is apparently so jaded, so numbed by her bourgeois existence that his assault barely seems to affect her; so the youth kills her, as he might have killed a sick animal.

Eirin, the censorship board, were plainly disturbed by this film and wavered over whether or not to pass it. Nikkatsu went ahead and submitted it to the Berlin Film Festival, despite government pleas to withold it presumably fearful of presenting a negative image of Japan to the Western world. At some point in the ensuing outcry, Nikkatsu apparently had a change of heart. Possibly fearful of a Black Snow-type prosecution, they opened the film for domestic release with muted publicity. Wakamatsu, feeling that his studio had betrayed him by this volte-face, quit and went off to form his own film company, Wakamatsu Productions. A few months later he had already directed and produced his first independent movie. [5]

In Secret Acts Within Four Walls, Koji Wakamatsu had sown the seed of his Cinema Psychotica, a seed which would flower spectacularly over the next few years with the release of such stunning, controversial works as Taiji GaMitsuryo Suru Toki (The Embryo Hunts In Secret); Okasareta Byakui (Violated Angels); Yuke, Yuke,Nidome No Shojo (Go, Go, Second Time Virgin); and Shojo Geba Geba (Geba Geba Virgin [6] ). These films at the core of Wakamatsus Cinema Psychotica comprise a brutally experimental/primal apocalypse which easily transcends the limitations of exploitation yet still impacts with a visceral force unequalled by any comparable sequence in Western cinema. [7] At implosion point, Wakamatsus films transgress into that zone of pure cinema inhabited by Bunuels UnChien Andalou, Kenneth Angers Inauguration Of ThePleasure Dome and a handful of others, a zone where logocentric notions of narrative are immolated and infernal meta-texts combust in the right brain like neural napalm.

Upon the release of his first autonomous production The Embryo Hunts In Secret (1966) [8], Wakamatsu was quoted in the Western press as proclaiming: For me, violence, the body and sex are an integral part of life; as borne out by the film and its successors, this proved to be less an artistic defense than a genuine manifesto. Palpably still enraged by the adverse reaction to Secret Acts, Wakamatsu throws into Embryo every sexual psychosis, cinematic gut-punch and accompanying outrage his revolutionary imagination can spew forth.

The plot of Embryo is simple; a disturbed man imprisons his girlfriend in his flat and subjects her to days of sadistic torture. But this simplicity is belied by the films complex execution, its restless experimentation and fathomless undercurrents of spiritual anguish. Wakamatsus Embryo is film as a physical weapon, a razor through the eye of the beholder. The short title sequence images of a foetus in utero set to choral music instantly sets a tone of quasi-religious regression. [9] Cut to a rainswept night scene, a man making love to a girl in his car. Soon he takes her into his building, carries her upstairs, and they enter his apartment and she enters a nightmare. The mans apartment is small (perhaps just two rooms), gloomy, oppressive the typical Wakamatsu mise-en-scne, a static space in whose confines a psychosexual rite inexorably unfolds, inevitably leading to death.

The man undresses the girl, again we see him making love to her but already the tone is far from that of a conventional pink movie; the odd musical score, unflattering close-ups, raw camera movements suggest alienation, hatred. Before long he has tied her wrists together then, fetching a bullwhip from a closet, he proceeds to attack her in a vicious, prolonged flagellation sequence, his laughter suggesting sadistic glee in the assault, until she lies bloody and striped with livid welts on the floor. For the remainder of the film he subjects the girl to similar whip onslaughts, various types of bondage, and, most disturbingly, torture with a straight razor. These scenes of intense cruelty are intercut with flashbacks in which the tormented man remembers his father abusing his mother in the same way; superimposed by images of religious martyrdom, the torture of women; and fragmented by Wakamatsus trademark freezeframes, bleaches and still montages. Wakamatsu sculpts fear from the viscosity of the rooms, their mausoleum shadows and textures, and also utilises their structure to compartmentalise his screen space. The mans sadistic reveries give shape, organic form to the films flux.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Pop Avant-Garde Violence: The Films Of Koji Wakamatsu»

Look at similar books to Pop Avant-Garde Violence: The Films Of Koji Wakamatsu. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Pop Avant-Garde Violence: The Films Of Koji Wakamatsu and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.