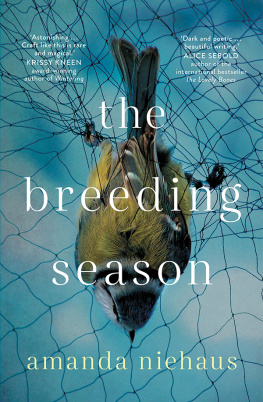

Amanda Niehaus [Niehaus - The Breeding Season

Here you can read online Amanda Niehaus [Niehaus - The Breeding Season full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Allen & Unwin, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Breeding Season

- Author:

- Publisher:Allen & Unwin

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Breeding Season: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Breeding Season" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Amanda Niehaus [Niehaus: author's other books

Who wrote The Breeding Season? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Breeding Season — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Breeding Season" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Robbie and Nelleyou were there in the waiting rooms with me, the treatment rooms with me, and when the scans were clear (and I was still afraid), you gave me the courage to be more than I was, more than I imagined I could be. This novel is that place. Our survival. Thank you to our cancer support teamShiro and Anne and Sally and Chris and Nicole, Choices, my Mater Mothers group. Lisa and Jenny, we said goodbye too soon.

Thank you to all my family, especially Mom, Dad, Kari, Aunt Sis, and Uncle Martin and Grandma N (we miss you), who carved out this Iowa heart I carry in me.

Thank you to all my dearest writerly companions! Renee Treml, Mary Mullen, Erin Langner, Charlotte Callander, Hana Broughton, Tanya Friedman, Christie Tate, and my fellow AWP mentees and Corporeal writersyou reminded me to keep writing, and made my words so much better. Thank you, Ryan McIlvainyour class (in both senses!) made all the difference.

Thank you, Krissy Kneen, Alice Sebold, and Lidia Yuknavitch for showing me how to write through my body and into the world; thank you to the Australian Society of Authors, the Australian Science Communicators, and the AWP Writer to Writer Mentorship Program (Diane Zinna, we love you!), whose awards made it possible to work with these phenomenal women. Thank you to Varuna, who gave me a fellowship to write, a room of my own, and all that rain.

Thank you to the Australian Research Council, who supported my research (and so, in a way, Elises), and to our Anindilyakwa friends on Groote, especially Jennifer, Jocelyn, Phillip, and Elma. Thank you to everyone who put in the hours (and hours and hours) on quolls and antechinusesbut especially Bec, Jaime, Skye, and Ami. To all my dear, dear friends who I havent namedthank you!

Finally, thank you to Gaby Naher, Jane Palfreyman, Ali Lavau, Tom Bailey-Smith, Lisa White, Louise Cornege, Pam Dunne, and all the Allen & Unwin team for the great love and care you have shown this book!

Theyre on a street called Boundary when the rain hits, flops onto the car with a cold, hard tapping that reminds him of fish, a shoal of hard-bodied fish throwing themselves against the metal shell of the car. Headlights double through the windscreen. The wipers pulse and cannot clear the slick of water, rush of water, its too much at once, he can hardly breathe.

Breathe.

He eases the car to the side of the road, into a small gravel patch overhung by a low, green tree. Rolls down his window and sucks in the air. Gasps it into his lungs like a trout. Out of water.

There, a park, wide and green, a park without cover. How odd, he thinks, that there is no shade. Nothing to protect the people or the picnic table or the barbecue or the swings or the climbing frame from the harsh Queensland sun. Storm.

There, a party, balloons and table decorations, bags of lollies and colourful boxes, a white-iced cake. Children are shrieking, crying, laughing, running. Just get in the car! someone shouts, muffled by rain.

No one, it seems, has prepared for this.

He doesnt want to be here with all these children, growing-up children. But he doesnt want to go home, either. The house will be damp and empty. A cottage built for workmen or families, young happy families.

Dan would like to have his son in his arms, to hold to his chest, skin on skin, like its supposed to be. He would like a cosy chair, worn and deep, a blanket; a place to warm him back to life. But his son is far away now, farther even than before, when he was inside her body. Gone.

The smack of the rain is a hollow, erratic sound. Dan reaches across and puts his hand on her leg, but she does not move. Elise, long-limbed and ghostly in a tidy black dress. Her head is swivelled towards the window beside her so that all he can see of her are her fine pale arms, hands in lap, strawberry hair pulled back into a low, smooth knot. She is facing the outside, but does not seem to be looking out.

He wonders if shes cold. What shes thinking.

I think the book was good, he says to her. He had read Goodnight Moon to the small white coffin, placed it on top before it was lowered. What else was there to say, but

Goodnight stars. Goodnight air. Goodnight noises everywhere.

Hed hoped the landscape might have made it easier, the cemetery full of jacarandas and great, top-sprawling eucalypts that surely had koalas in them, though he hadnt seen any. Hed hoped it might hurt less with all the fine-faced wallabies clustered at the propertys edge, tipping down into the long grass and upright again, forepaws tucked close against their chests.

But, no. It was stupid to think any of it would help.

The box made everything worse. Dan was set apart from his child by a winding drive out of the city, and a volume of dirt and turf and flowers. But it was the box he hated. The coffin that would never disintegrate, not in a hundred years, that would keep his boy apart from all the beautiful, terrible wildness in the world. Hed rather he was ashes. He would have liked to imagine William as a tree or a marsupial, atoms or cells bounding across the open spaces.

But he didnt get to make that choice.

He stares at her neck, wills her to speak.

Where are we, she says, after a few moments. Her voice is flat. It isnt a question. He cant tell if she really wants to know, but it doesnt matter anyway. He has no answer.

When the rain pauses, he guides them back onto the road, but the too-early dusk and the unfamiliar streets disorient him, and without her to navigate, he gets lost. Theyve lived in this city for two or three years now, long years in which he cant get his bearing east or west, north or south, for the river that snakes up the middle. He has the sense hes driving in a wide undulating circle, Mount Coot-tha at the centre. A cemetery on every side.

He drives and drives, and she doesnt move.

But he gets them home, and into the house, where he pulls off her flats and her dress and guides her into the bedsheets in her underwear. Its only April, but he tugs the winter quilt from the top shelf of the wardrobe and drapes it over the lump of her body. It occurs to him that she might need to change her pad, but she is so still and quiet that he doesnt want to move her. Shes like something in a museum, a mechanised doll, a sculpture of a human.

One of his uncles artworks.

Somehow she has slipped beyond blood and discomfort, beyond her body even. He envies her emptiness. Resents it. Because in his own body, every ache or stab or itch is amplified. A blister on his heel, rash on his chest. Something pulses at the back of his eyes.

Though its dinnertime, hes not hungry. He changes into flannel pants and a t-shirt, pours a glass of single malt and takes it into the spare room to work.

The spare room. Not-spare. Spare again.

The cot now disassembled in the corner.

Dan sits at his desk and does not look at the cot or the pile of washcloths and blankets and onesies on the floor beside it. Hes avoided this room since he tore the cot apart. Avoided as much as he can.

The low rumble of thunder.

They used to make love when the storms came, he and Elisecurtains open, doors wide, the cool breath of rain pouring into the room and over the bed and into their skin.

Skin, he thinks. Singular.

They used to slide into one body and move it together through a dark world, brush the thorns off like flies.

Now, on his own, the thorns stick.

Like the art above his desk, where so much skin is pinned up like a crime scene. Not Elises skin or his or the babys (too soft)this is art with a capital A. Dismembered bodies clipped from magazines, printed, sketched. Women, mostly, or parts of women. The images sicken him, like a car crash, a murder-suicide. But he cant stop looking.

Art.

Made by his uncle, a man who barely needs a name to be known, a man Dan has never met.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Breeding Season»

Look at similar books to The Breeding Season. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Breeding Season and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.