Southwestern Writers Collection Series

The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University

STEVEN L. DAVIS, EDITOR

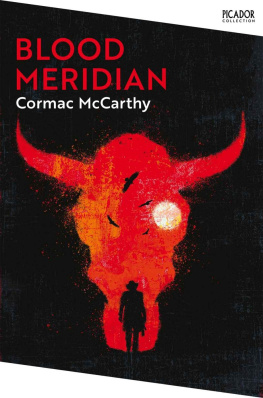

Books Out of Are Books Made

A Guide to Cormac McCarthys Literary Influences

MICHAEL LYNN CREWS

University of Texas Press

AUSTIN

The Southwestern Writers Collection Series originates from the Wittliff Collections, a repository of literature, film, music, and southwestern and Mexican photography established at Texas State University.

Nelson Algren, excerpts from Tricks Out of Times Long Gone from Algren at Sea. Copyright 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963 by Nelson Algren. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, Inc., on behalf of Seven Stories Press, www.sevenstories.com.

Copyright 2017 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

First edition, 2017

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

http://utpress.utexas.edu/rp-form

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING DATA

Names: Crews, Michael Lynn, author.

Title: Books are made out of Books : a guide to Cormac McCarthys literary influences / Michael Lynn Crews.

Other titles: Southwestern Writers Collection series.

Description: First edition. | Austin : University of Texas Press, 2017. | Series: Southwestern writers collection series, The Wittliff collections at Texas State University | Include bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017003553| ISBN 978-1-4773-1348-0 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 978-1-4773-1469-2 (library e-book) | ISBN 978-1-4773-1470-8 (non-library e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: McCarthy, Cormac, 1933

Classification: LCC PS3563.C337 Z64 2017 | DDC 813/.54dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017003553

doi:10.7560/313480

For Denise, Jane, and Danny

And for James Barcus,

Requiescat in Pace

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to my wife, Denise, and our children, Jane and Danny, for keeping my spirits up.

From Baylor University, Sarah Ford, Luke Ferretter, and Richard Russell all provided helpful feedback on the book. Richard, in particular, has been a source of encouragement and inspiration. He has served as a model of scholarly integrity, one I have tried to emulate.

James Barcus, also from Baylor, and sadly no longer with us, deserves special thanks. This book was launched from a conversation over coffee with him, and he helped shepherd it through its first iteration. His enthusiasm for the book, for the work of Cormac McCarthy, and his generous support of my endeavors were invaluable to me. I miss him and wish he could have seen the book in print. He was its first champion.

Thanks to Katie Salzmann and Steve Davis at the Southwestern Writers Collection, Texas State UniversitySan Marcos. Without Katies exceptional work, my own would not be possible. Thanks to Rick Wallach, for very kind words, and for his contribution to McCarthy studies.

I would also like to thank everyone at the University of Texas Press who worked on the publication of this book, especially Casey Kittrell, who shepherded it through its second iteration. And thanks to Katherine H. Streckfus, whose keen eye helped me to make this a better book.

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Books Out of Books

In 1992, Cormac McCarthy granted his first lengthy interview in a career spanning three decades. Asked to comment on his literary influences, he told the interviewer, Richard B. Woodward, that the ugly fact is books are made out of books.... The novel depends for its life on the novels that have been written. In the same interview, Woodward informs us that McCarthy would rather talk about rattlesnakes, molecular computers, country music, Wittgensteinanythingthan himself or his books. Critics interested in the questionone inevitably asked about a writer whose work one admiresof McCarthys literary interests and influences have had to sustain themselves on scraps. We know that Moby-Dick is his favorite book, and that he admires Joyce, Faulkner, and Dostoyevsky. These names make up the litany that he can be counted on to volunteer. Digging through the nooks and crannies of his meager offerings to literary journalists, we could add Tolstoy, Flannery OConnor, and Shakespeare. These are nutritious enough hors doeuvres, but hardly satisfy the appetites of those who are fascinated by the ways in which, to borrow McCarthys formulation, books are made out of books. To call this an ugly fact suggests that something like Harold Blooms anxiety of influence haunts McCarthys creative efforts. But, for the critic, this fact is a tantalizing invitation to research.

However reticent McCarthy may be in interviews about discussing his booksor the influence of other books on themby making his literary papers available to scholars, he has made it possible to begin research into his influences in earnest. In December 2007, the Southwestern Writers Collection (SWC), which is part of the Wittliff Collection of the Alkek Library at Texas State University, in San Marcos, Texas, purchased a sizable collection of McCarthys papers, which became available to scholars in the spring of 2009. The collection includes notes, correspondence, and drafts. The acquisition of correspondence between McCarthy and J. Howard Woolmer, a rare book dealer and publisher, added another source of information about McCarthys reading habits. It is now possible to offer a tentative answer to the following question: What books, what writers, were on McCarthys mind during the composition of his novels? In his notes, in letters to Woolmer and others, and often in holograph marginalia found in early drafts of the novels, McCarthy tells us himself. And by examining the way in which these books went into the making of his own, we can learn something about the way influences shape McCarthys own imaginative endeavors. What follows will be an extended study of Cormac McCarthys reading interests and influences, but only those that can be identified through direct references in the archives. Writers that McCarthy has mentioned in interviews, or who can be identified through clear literary allusions in his published works, are outside my province.

For instance, McCarthys interest in Emily Dickinson is signaled by the following allusion in Child of God. Lester Ballard, upon waking up in the hospital to discover that his arm has been amputated, is described as noting the ghastly absence apparently with no surprise (175). The poem to which this alludes begins with the following lines: Apparently with no surprise / To any happy Flower / The Frost beheads it at its play (Poem 1668). Any reader acquainted with the poetry of Dickinson could identify the source of the allusion. The focus of my research is on references to other writers that do not appear in any publication, references that can only be found in the Wittliff archives. Since no reference to Dickinson appears in the archives, I do not include an entry for her. The following project is the fruit of exclusively archival research, and my purpose is to provide readers with information that was not available until McCarthys papers became available.

The main body of this work is comprised of alphabetized entries corresponding to the names of writers or thinkers to whom McCarthy clearly refers in his papers. These entries consist of a description of the location of the reference within the archives, and some context, such as biographical information about the author, or the location in the source text of a quotation that McCarthy has copied into his notes or margins. I then establish a connection between these references to other writers and McCarthys own work. In some cases, I draw out some interpretive conclusions on the basis of that connection. The entries explore McCarthys influences and interests as revealed by the books he was reading during the composition of his novels.

Next page