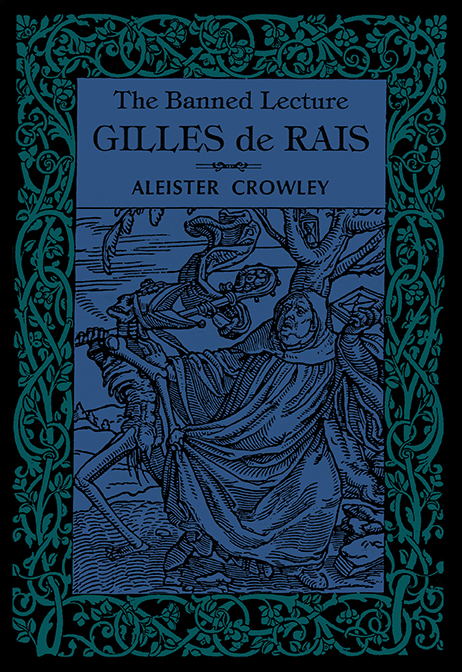

The Banned Lecture GILLES de RAIS to have been delivered before the University Poetry Society by ALEISTER CROWLEY on the evening of Monday, Feb.3rd.1930 Long ago when King Brahmadatta reigned in Benares, a gentleman whose Christian names were Thomas Henry - you possible have heard of him - he was no less apersonage than the Grandfather of the great Aldous Huxley- once found himself threatened be a perdicament similar to that in which I stand tonite. He had been asked to lecture a distinguished group of people. What bothered him was this: what assumption was he to make about the existing knowledge of the audience? He adoted the sensible course of asking the advice of an old hand at the game; and was told "You must do one of two things. You may assume that they know everything, or that they know nothing." Thomas Henry thought it over, and decided that he would assume that they know nothing. I think that merely shows how badly brought up he must have been; and explains how it was that he became a kirty little atheist, and repented on his death-bed, and died blaspheming. Gilles de Raise was born sometime in 1404. He married Catherine de Thonars on the 30th of November, 1420, thus becoming the richest noble in Europe. He lived extravagantly until his arrest by the Church. He geban alchemical studies under the instruction of Gilles de Sille, a priest of St. malo. Montague Summers believes he sacrificed around eight hundred children and quotes the proceedings of ecclesiastical high court in which a Dominican priest named Jean Blouyn took over as the delegate of the Holy Inquisition for the city and diocese of Nantes. Needless to say, Gilles "confessed", and was put to the stake and charcoaled on October 26th., 1440 leaving his estates and untold riches to Mother Church, who, wasting no time, added them to her list of material gains. Included in this particular catche were Gilles personal hand-painted manuscripts which were eagerly welcomed into the Mother Lodes vault where they sit to this day. Unfortunately, the Vaticans library is inaccessible to "common folk", and will probably remain so until the demise of Mother Church herself, at which time this author will assist other interested persons in converting it into a public library. No! No! that would be quite impossibly bad manners. I shall assume that you know everything about Gilles de Rais; and that being the case, it would evidently be impertinent for me to tell you anything about him. So that we can consider the lecture at an end, and (after the usual vote of thanks) pass on immediately to the discussion, which I think ought to be more amuising, if scarcely as informative. It is rather an hard sayinghowever worthy of all acceptation in a university like Oxford, where, I understand, the besetting sin of the inmates is lecturing and being lectured, but discussions are always apt to turn out to be amusing, especially if conducted with blackthorns or shotguns, where as lecturing is merely an attempt, fordoomed to failure, to communicate knowledge which usually the lecturer does not possess. I am sure that we all recognise that an attempt of this kind is impossible in nature. No! I am not proposing to inflict upon you my celebrated discourse on Scepticism of the Instrument of Midn. I am not even going to refer to the first and last lecture which I suffered at a dud university somewhere near Newmarket, in which the specimen of old red sandstone in rostrum began by remarking that political economy was a very difficult subject to theorise upon because there were no reliable data. Never would I tell so sad a story on a Monday evening, with the idea of Tuesday already looming darkly in every melancholic mind. I should like to be just friendly and sensible, though it is perhaps too much to expect me to be cheerful. The fact is that I am in a very depressed state. My attention was attracted by that little work "knowledge" of which we hear so much and see so little. I dont pr&127;pose to inflict upon you the M.C.H., and demonstrate that the life and opinions of Filles de Rais were inevitably determioned by the price of onions in Hyderabad. But I do think that in approaching a historic question, we should be very careful to define what we meanin our particular universe of discourseby the work "knowledge." May I ask a question? Does anyone here know the date of the battle of Waterloo? Pause-- (SomeoneI bettells me "1815.") Thank you very much. To be frank with you, I know it myself. I did not require information on that particular point. What I asked was, wheter anyone know the date. I felt that, if so, it would have created a sympathetic atmosphere. But since we are talking about Waterloo, we may ask ourselves what, roughly speaking, is the extent of our knowledge? I have heard plenty of theories about why Napoleon lost the battle. I have been told that he was already suffering from the disease which killed him. I have been told that he was outgeneralled by Wellington. I have been told that his army of conscripts was underfed and not properly drilled. I have also been told that the battle was won by the Belgians. Now, all these things are merely matters of opinion. There may be a little truth in some of them. But we have practically no means of finding out exactly how much, even if our documentary support is valid to establish any of these theories. It is, also, almost impossible to estimate the causes of any given event, if only because those causes are infinite, and each one of them is to a certian extent an efficient determining cause. Take a quite simple matter like the time of year. If it had been winter instead of summer, the hens would not have been laying and Hougomont and La Haye Sainte would not have been able to nourish the contending forces. But though it is profitable for the soul to contemplate the extent of what we dont know, it is in some ways more satisfying to our baser natures to consider what we do know in a reasonable sense of the word. It is not disputable that the battle of Waterloo was fought and won. It is not disputable that it was the climax, or rather the denoucement, of campaigns lasting over a number of years. And there is no reason for doubting that Napoleon was born in Corsica, that he entered the French army, and rose rapidly to power by a combination of military genius and political intrigue. There is a vast body of indirect evidence which confirms these statements at every point. Taken as a whole, they would be totally inexplicable on any other hypothesis. But when we consider the character of Napoleon, we are at once involved in a mass of contradictions. Probably no one in history has been more discussed, and every writer gives a totally different account. Each seeks to buttress his opinion by incidents which we have no reason to suppose other than authentic, but seem incongruous. So far as we can get any truth out of the matter at all, it is that the character of Napoleon, like that of everybody who ever lived, was extremely complex. And the writers are more or less in the position of the Six Wise Men of Hindustan who were born blind and had to describe an elephant. Spiritually fortified by these simple meditations, we may apply their fruits to the problem of Filles de Rais, and ask ourselves what we really know about hime as oposed to what we have heard about him. We know that he was a gentleman of good family, because otherwise he could not have held the offices which he did hold. We know that he was a brave soldier, and a comrade of Joan of Arc. We know that he had a passion for science, for the basis of his reputation was that he frequented the society of learned men. We know finally that he was accused of the same crimes as Joan of Arc by the same people who accused her, and that he was condemned by them to the same penalty. |