ALSO BY TONI MORRISON Fiction The Bluest Eye Sula Song of Solomon Tar Baby Beloved Jazz Paradise Love A Mercy Home God Help the Child Nonfiction Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination The Origin of Others The Source of Self-Regard  THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF AND ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA Copyright 2019 by The Estate of Chloe A. Morrison Foreword copyright 2019 by Zadie Smith All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Alfred A.

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF AND ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA Copyright 2019 by The Estate of Chloe A. Morrison Foreword copyright 2019 by Zadie Smith All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Alfred A.

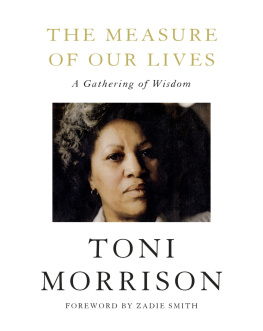

Knopf Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. www.aaknopf.com www.penguinrandomhouse.ca Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Knopf Canada and colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. A version of the Foreword first appeared as Daughters of Toni: A Remembrance by Zadie Smith in PEN America as part of Tribute to Toni Morrison (19312019) on August 7, 2019. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019952413 ISBN9780525659297 (hardcover) | EBOOK ISBN9780525659303 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Title: The measure of our lives : a gathering of wisdom / Toni Morrison ; foreword by Zadie Smith. Names: Morrison, Toni, author.

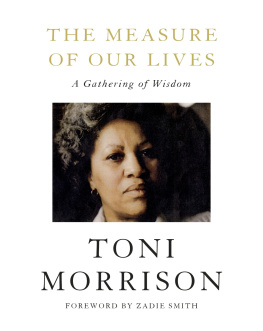

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190202149 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190202165 | ISBN 9780735280236 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780735280243 (HTML) Subjects: LCSH: Morrison, ToniQuotations. Classification: LCC PS3563.O8749 M43 2019 | DDC 813/.54dc23 Cover photograph by Bernard Gotfryd/Getty Images Cover design by John Gall v5.4 ep Contents FOREWORD I READ TONI MORRISONS EARLY NOVELS very young, probably a little too young, when I was around ten years old. I couldnt always follow her linguistic experiments or the density of her metaphoric expressions, but at that age what mattered more even than her writing was the fact of her. Her books lined our living room shelves and appeared in multiple copies, as if my mother was trying to reassure herself that Morrison was here to stay. Its hard now, in 2019, to recreate or describe the bottomless need she answered. There was no black girl magic, in London, in 1985.

Indeed, as far as the broader culture was concerned, there was no black girl anything, outside of singing, dancing, and perhaps running. On my mothers shelves there certainly were black woman writers, and Toni was first amongst them, but no such being was ever mentioned in any class I ever attended, and I cant remember ever seeing one on the TV or in the papers or anywhere else. Reading The Bluest Eye, Sula, Song of Solomon, and Tar Baby for the first time was therefore more than an aesthetic or psychological experience, it was existential. Like a lot of black girls of my generation, I placed Morrison, in her single person, in an impossible role. I wanted to see her name on the spine of a book and feel some of the same lazy assumption and smug confidence of familial relation, of inherited potential, that any Anglo-Saxon boy in school feltno matter how unlettered or indifferent to literaturewhenever he heard the name of William Shakespeare, say, or John Keats. No writer should have to bear such a burden.

Whats extraordinary about Morrison is that she not only wanted that burden, she was equal to it. She knew we needed her to be not just a writer but a discourse and she became one, making her language out of whole cloth, and conceiving of each novel as a project, as a missionnever as mere entertainment. Just as there is a Keatsian sentence and a Shakespearean one, so Morrison made a sentence distinctly hers, abundant in compulsive, self-generating metaphor, as full of sub-clauses as a piece of 19th century presidential oratory, and always faithful to the central belief that narrative languageinconclusive, non-definitive, ambivalent, twisting, metaphorical narrative language, with its roots in oral culturecan offer a form of wisdom distinct from and in opposition to, as she put it, the calcified language of the academy or the commodity-driven language of science. The thwarting of human potential was her great theme, but there was nothing subconscious or accidental about itshe couldnt afford there to be. In The Bluest Eye, for example, how do you write about self-loathing without submitting to the same? Or demonizing the habit? Or handing the power of victory precisely to the culture that has created the feeling? All of it had to be thought through, and she thought about all of it, as a working novelist but also as a critic and academic. To me the most astonishing section of her final book of essays, The Source of Self- Regard, is the level of sustained academic critique she was able to bring to bear upon her own novels, like an architect walking you through a building shed made, with the same consciousness of its beauty but also of its use.

Toni Morrison put herself in the service of her people, as few writers have ever been called upon to do, and she claimed it as a privilege. A large part of the project was the ennobling of black culture itself and its deliberate encasement in a vocabulary worthy of its glories. To those who considered the entrance to her buildings narrow she had many famous rejoinders. And nowin no small part because of her determination not to be swayed from her projectwe of course understand that there are no such things as narrow entrances into the houses of history, experience, and culture. For when it comes to ways of telling, ways of seeing, every mans story is infinite. Every black womans, too.

This infinite terrain is what she opened up for girls like me who had feared otherwise. Zadie Smith, August 7, 2019 PUBLISHERS NOTE Through bricolageconstruction or creation from a diverse range of available thingsthis brief book aims to limn the totality of Toni Morrisons literary vision and achievement. It dramatizes the life of her mind by juxtaposing quotations, one to a page, drawn from her entire body of work, both fiction and nonfictionfrom The Bluest Eye to God Help the Child, from Playing in the Dark to The Source of Self-Regard . Its sequence of flashes of revelationremarkable for their linguistic felicity, keenness of psychological observation, and philosophical profundityaddresses issues of abiding interest in Morrisons work: the reach of language for the ineffable; transcendence through imagination; the self and its discontents; the vicissitudes of love; the whirligig of memory; the singular power of women; the original American sin of slavery; the bankruptcy of racial oppression; the humanity and art of black people.  We die. That may be the meaning of life.

We die. That may be the meaning of life.

But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.  My nature is a quiet one, anyway. As a child I was considered respectful; as a young woman I was called discreet. Later on I was thought to have the wisdom maturity brings.

My nature is a quiet one, anyway. As a child I was considered respectful; as a young woman I was called discreet. Later on I was thought to have the wisdom maturity brings.  Sweet, crazy conversations full of half sentences, daydreams and misunderstandings more thrilling than understanding could ever be.

Sweet, crazy conversations full of half sentences, daydreams and misunderstandings more thrilling than understanding could ever be.  Their conversation is like a gently wicked dance: sound meets sound, curtsies, shimmies, and retires.

Their conversation is like a gently wicked dance: sound meets sound, curtsies, shimmies, and retires.

Next page

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF AND ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA Copyright 2019 by The Estate of Chloe A. Morrison Foreword copyright 2019 by Zadie Smith All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Alfred A.

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF AND ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA Copyright 2019 by The Estate of Chloe A. Morrison Foreword copyright 2019 by Zadie Smith All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Alfred A. We die. That may be the meaning of life.

We die. That may be the meaning of life. My nature is a quiet one, anyway. As a child I was considered respectful; as a young woman I was called discreet. Later on I was thought to have the wisdom maturity brings.

My nature is a quiet one, anyway. As a child I was considered respectful; as a young woman I was called discreet. Later on I was thought to have the wisdom maturity brings.  Sweet, crazy conversations full of half sentences, daydreams and misunderstandings more thrilling than understanding could ever be.

Sweet, crazy conversations full of half sentences, daydreams and misunderstandings more thrilling than understanding could ever be.  Their conversation is like a gently wicked dance: sound meets sound, curtsies, shimmies, and retires.

Their conversation is like a gently wicked dance: sound meets sound, curtsies, shimmies, and retires.